“Roy was the first person to come and see me after I had my daughter,” says Anne Francis. “He snuck into the hospital about an hour after she was born. I think he wanted to see what colour she was. It was quite touching, I thought.

“He didn’t say that of course, but I know why he came. I could see him looking at her in the cot, and he went home and told his wife Rene he was so relieved she was white. He didn’t want his granddaughter to have any hassle, and he adored her.”

The story Anne recalls of her father-in-law Roy Francis is far removed from his public profile and great sporting successes, but it gives a poignant insight into the mind of a loving and private man who achieved plenty in the public sphere.

Francis was a brilliant rugby league player, becoming the first black man to play for Great Britain in 1947, and one of the country’s greatest coaches. At Hull FC in 1955, he became the first black head coach of a British top-tier professional team.

But why did he want his granddaughter to be white?

As a coach, Roy Francis had become a leader with authority over white men in Britain at a time when that would have been unthinkable in all other areas of society. Colour bars in the 1950s prevented many black people from getting jobs. It would be 23 more years before Viv Anderson became the first black man to play football for England, and 32 more years before Bernie Grant became the UK’s first black MP.

Francis’ story has been largely forgotten. He died in 1989, aged 70. He is not in Britain’s wider sporting consciousness, and he is not on the list of 100 Great Black Britons. Yet he was a great innovator who revolutionised sport in the country.

Growing up in south Wales in the 1920s and 30s, Francis fell in love with rugby union.

But the Welsh had followed England’s Rugby Football Union in 1895 in splitting from rugby league. Northern England’s working classes sought payment for their on-pitch efforts, while the union men wanted to keep rugby amateur for ‘gentlemen’.

A working class man needing to earn money, Francis had only one path to take. Welsh rugby union’s loss would be English rugby league’s gain.

Roy Francis had been born in 1919 in Brynmawr. His birth mother, a married white woman, had an affair with a West Indian man. Her family were unimpressed when baby Roy was born, and she gave him away. It is not clear if he ever knew who his birth parents were.

A black woman – Rebecca Francis – took Roy in and raised him. School reports show he was a brilliant all-round pupil who excelled at a multitude of sports.

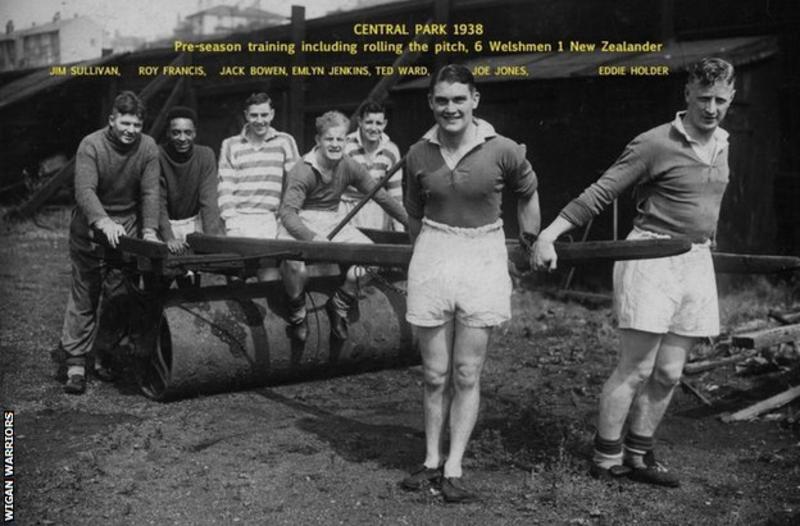

He initially played rugby union for Brynmawr before becoming one of the first black rugby league players when he switched codes and made the journey north to Wigan as a 17-year-old in 1936.

The teenager was an instant success, making his first five appearances in the sport at the end of that season and scoring seven tries.

Supporters took him to their hearts. Francis developed rapidly, but his progress was curtailed when the Australian Harry Sunderland took over as coach and played the youngster in only seven of 86 games.

The young winger was told he would not succeed at the club and it has been suggested – including by Francis himself – that the colour of his skin was the reason for his departure.

Barrow saw a chance to sign him. Francis joined the Cumbrian club in January 1939 and began notching up tries at an astonishing rate, before World War Two hit.

During the war, he joined the British army and served as a physical training instructor across the north of England, alongside future Manchester City boss Joe Mercer and many other sportsmen of the time.

This period in the military did not stop Francis’ participation in sport. He was crowned the fastest sprinter in the Army in 1942 and turned out as a Dewsbury guest player on 57 occasions, winning two Championship medals in the process.

Roy Francis became a sergeant and was called upon by the Army rugby union teams to represent both England and Wales. He was also obsessively absorbing knowledge that would soon become crucial.

Post-war, Francis returned to Barrow and his prolific form thrust him into the Great Britain reckoning to tour Australia. Unfortunately, he came up against another glass ceiling.

Writing Francis’ obituary in 1989, the author Robert Gate reflected: “Roy’s skin deprived him of a place on the 1946 Lions tour. There were clearly not four better wings in the game and yet he was left out for political reasons, Australia still operated a colour bar.”

One year later, on 20 December 1947, he became the first black man to play for Great Britain, in the third Test against New Zealand in Bradford.

Great Britain won 25-9. Roy Francis scored two tries. He was never selected again.

In his book Gone North: Welshmen in Rugby League, Gate notes an observation of Francis from a Dewsbury match: “He is a man capable of snatching the vital try at a critical stage, he is also talented at keeping up the morale of his team generally. It is he who, with a choice remark or slight action, can rapidly dispel the tension of a critical moment.”

This analysis proved to be an accurate early hint of Francis’ prodigious future impact. His cerebral qualities would change the entire game.

By 1950, Francis had arrived at Hull, via Warrington, signed for £1,250 (the world record fee was £4,750 that year). He continued on the pitch before becoming player-coach, hanging up his boots with the astonishing record of 229 tries in 356 games.

Five years after his arrival, he became the team’s head coach.

Francis was a revelation. He brought a golden era to the city with Championship titles in 1956 and 1958 – finishing as runners-up in between – and took them to the Challenge Cup final in 1959 and 1960.

Everyone at the club loved him, the people of Hull loved him. Francis’ brilliance and the city’s accepting nature combined to create a bubble away from the racial tensions elsewhere in Britain.

But it is not the accolades and silverware that Francis is chiefly remembered for, it is the manner in which he sought them out.

At the time in British sport, coaches were often merely team-pickers. The holistic view of Clive Woodward’s England rugby union successes or Sir Dave Brailsford’s ‘marginal gains’ at British Cycling were decades away. Not for Francis.

“He was really the first person in British sport to use modern coaching methods,” says sports historian Tony Collins.

“There were specialist coaches to develop player skills, sprint coaches, individual training plans and diets for players. He was very concerned with psychological welfare and always made sure wives and children were involved.”

Roy Francis had two sons, Geoff and Ian, who saw what his father’s all-encompassing approach meant at home.

“Our house was always full of injured players,” Geoff says. “Guys with concussions or whatever would come and stay with us for a few days. Players were in and out of our house like drafts.

“Roy was like an agony aunt to players. If they were having problems at home or whatever, he would sit with them for hours.”

Francis and his wife Irene, a sociable and embracing woman who everybody called Rene, also successfully ran three pubs and a coffee shop during their time at Hull. It created their own community.

Those who didn’t like it did not last long. In 1957, Hull signed a South African full-back called Mervyn ‘Pin’ McMillan, who was not aware his coach was black.

Francis went to pick up his new player from the train station and the South African’s disdain was immediately clear. McMillan pointed out that back in his home country, Roy Francis would have been carrying his bags rather than coaching. He did not make it into Hull’s first team.

The leaps forward in physical training and psychology studies in the Army had helped Francis revolutionise Hull. Next he would do the same at Leeds, becoming their head coach in 1963.

“What a transformation, his training methods were a revelation,” recounts Alan Smith, a wing for Leeds, England and Great Britain, who retired in 1983.

“Straight away everybody had to have spikes, big forwards wearing sprinting spikes. He lifted the fitness, he changed the game and took rugby to a new level – the finest pre-Super League rugby. He was a lovely man. He was like a pied piper.”

It is now commonplace for coaches to take inspiration from other sports – but Francis was years ahead of his time in this regard.

He was obsessive about sport. His son Geoff recalls that he held a British Boxing Board of Control trainer’s license for three years, ordering his boxers to carry 5lb weights in their hands on training runs.

Pain was a common thread in Francis’ training. “Lads were regularly physically sick,” Smith says of the early Leeds sessions. “We’d never seen anything like it.

“He pushed and he pushed and he pushed and he always had his stopwatch out, I’m not sure he ever recorded the times, I think it might’ve been a trick.

“He loved us and we loved him. Every player there – if Roy had said ‘run all night’ we would’ve done. I haven’t trained under anyone better.”

Francis’ Leeds played beautiful rugby, forwards passing the ball wide, backs tackling hard. In 1968, there was a trophy to show for it, as they beat Wakefield in a downpour to win the Challenge Cup, in what became known as the ‘Watersplash final’.

Unfortunately for Leeds, their coach’s reputation had grown further still, and his story would cross paths with Australia once again, with the North Sydney Bears attracting him in time for the 1969 season.

Some say the club hierarchy did not realise Francis was black when they hired him. That is unclear, but the world of that time did not share British rugby league’s view that if you can do a job, it does not matter what colour you are.

On the long journey to the other side of the globe, Francis and his wife Rene were not allowed off the boat in South Africa. They arrived in an Australia where Aboriginal people had only become able to vote, or counted in the census, two years previously.

Like many men of his generation, Francis wasn’t prone to discussing his feelings with family, but Rene did speak to her daughter-in-law Anne.

“Rene had to put up with a lot of abuse from people in Australia, they were very cruel,” Anne says. “Both she and Roy kept quiet about it, but I think they were very hurt by the abuse they received by some members of the team.”

Ludicrously, one comment in the Australian media labelled Francis a “militant” who was “acting like Malcolm X”, and then, during a live radio interview, the British coach – tired of such comments – suddenly pulled out his earplugs and walked out of the studio.

After two years, Francis had had enough. He and Rene were coming home.

After Sydney, Francis returned to Hull for three years from 1970, to Leeds once again in 1974 where he won the Premiership title, before finishing his coaching career with Bradford Northern and Huddersfield. He retired in 1977, aged 58.

Only recently has Francis’ impressive legacy begun to be recognised properly. He was inducted into the Welsh Sports Hall of Fame in 2018, and there is a new campaign to have a statue of him erected in Cardiff.

Looking at Francis’ proteges, his influence stretches far and wide.

Johnny Whiteley was Hull captain under the progressive coach and took over the reins himself, later leading Great Britain on tour to Australia in 1970, the last side to win the Ashes there. Colin Hutton picked up Francis’ methods and became a rugby league great, also coaching Great Britain in the 1960s.

Yet 65 years on from Francis’ trailblazing start at Hull, there remains a galling lack of black head coaches or administrators in British sport – something footballer Raheem Sterling highlighted in June.

Francis had innumerable qualities: inner strength, thick skin, a uniquely-innovative sporting mind, and a loving nature.

Last month, Bradford Bulls head coach John Kear hailed Francis as “the godfather of the modern coach”, but to Roy’s son Geoff, he was just Dad.

“I’ve not come across anyone like him since,” he says. “I know he’s my father and blood’s thicker than water. I don’t know how to phrase it really, I can’t think of anyone else I’ve met in my life that I’ve thought ‘this bloke is really something else’.

“I’m very proud of him.”