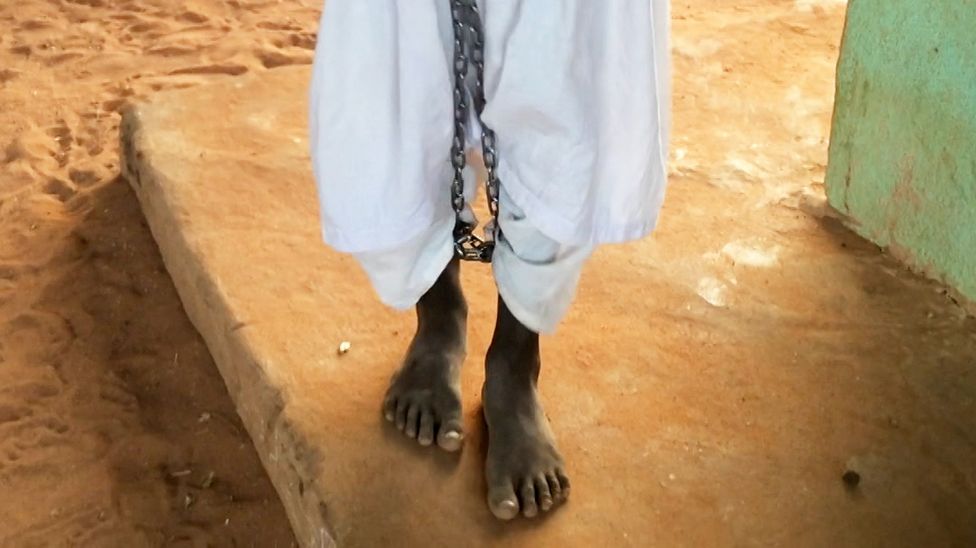

When I meet Ahmed, he is shackled in a room all alone. There are marks on his body from the beatings he has been given. He doesn’t know how old he is, but he’s probably about 10.

The school I find him in is one of 23 Islamic educational institutions in Sudan, known as khalwas, that I filmed in undercover over a two-year period, starting in early 2018.

I witnessed and filmed many children, some just five years old, being severely beaten, routinely shackled, and imprisoned without food and water by the sheikhs, or religious men, in charge of the schools. Some of the children who did not appear in our documentary told me they had been raped or experienced other forms of sexual abuse.

There are nearly 30,000 khalwas across the country, according to the Sudanese government. They receive money from the government and private donors both in Sudan and around the world.

Children are taught to memorise the Koran. Because they charge no fees, many families consider them an alternative to mainstream education, especially in remote villages that may not have government-run schools. Students board there, only returning home for the holidays.

To many people the schools, which have been operating for generations, are a central element of Sudanese culture, seen as part of the national identity.

However, in recent years, videos of children being beaten in the schools have been widely shared on social media, and there have been stories in local media of sheikhs accused of rape in the khalwas. The media, the government and even human rights organisations have ignored this.

I wanted to expose how widespread the abuse was, and give a voice to these children who don’t have the opportunity to share their stories.

And I had had my own experiences. As a teenager, I attended a khalwa. Every day was a trial to avoid being beaten by the teachers.

I knew I’d fall out with friends and family over this investigation, but the story needed to be told. Even though along the way, I would be accused of being part of a “Western plot to attack religious education” by some of the people I spoke to.

By the time I contacted the BBC, I had already spent several months filming undercover on my own. One of the first khalwas I visited was called Haj el-Daly, where I had been told abuses took place. I slipped into the school’s mosque to pray with everyone else at noon prayers, secretly filming on my phone as I did so.

As I knelt, I heard a clanging sound. My heart stopped. I looked up and saw the children in front of me had their legs bound in chains, shackled like animals.

Prayers ended, and the children shuffled out. But as I made to leave I heard violent shouting and muffled crying.

I followed the sound to a dimly lit study room nearby, where I found a child quietly sobbing, his legs chained together. I began to secretly film what I was seeing. This was Ahmed. He told me he wanted to go home. I tried to reassure him but I could hear the voices of the sheikhs approaching, stopped filming and left the khalwa.

But I returned the following day so I could reveal more about what was happening there. As I was talking to the children, trying to film them with my phone, I noticed an older student watching me. He left suddenly and moments later returned with the sheikh in charge of the school. The sheikh started shouting at me, asking why I was filming the students. I managed to quickly run out of the door into the street.

Haj el-Daly’s management have since told the BBC that there is a new sheikh in charge of the school and that the beating and chaining has stopped.

Memories of my own khalwa

I got home feeling shaken – if the confrontation with the sheikh had escalated, no-one would have known where I was. But I was also traumatised by what I had seen. It brought back memories of my own time in a khalwa as a teenager, where beatings were commonplace, though no-one was shackled.

I had been so excited for my first day at that khalwa when I was 14, trying on my jalabiya – traditional dress – and impatiently waiting for morning. But early on, I could tell something was not right. I noticed the other children seemed afraid of the sheikhs and the teachers.

The abuse began in the evening sessions. If we were sleepy and closed our eyes, the sheikh would whip us. That would certainly wake us up. I stayed in the khalwa for about a month, enduring many beatings. When I returned home, I told my parents that I didn’t want to go back, although I didn’t feel I could tell them about the abuse I had suffered. They weren’t happy about me breaking off my studies, but they didn’t force me to return.

Following the altercation with the sheikh in charge of Haj el-Daly, I was finding it difficult to get my confidence back to continue filming in the khalwas. I took my evidence to the Arab Reporters in Investigative Journalism (ARIJ), who put me in touch with BBC News Arabic. From that point, everything changed.

My editor in London assigned me a producer, Mamdouh Akbik. He’s Syrian and I’m Sudanese, and although we both speak Arabic, our dialects are very different. But it wasn’t long before we were working together really well.

We mapped out the khalwas, we gathered evidence, and we talked about safety and logistics throughout. But the real game changer was when I received the secret recording equipment. It gave me the confidence to continue my work.

Sudan is a vast country, encompassing mountains, the Red Sea and wide desert plains. During the course of the investigation, I must have covered 3,000 miles of it, mostly by bus.

I met families whose sons had been badly abused. In some cases they had died while at the schools and it was difficult to establish a cause of death.

Sheikhs wield so much power and influence in their communities that it’s rare for families to press charges against them. Cases that do make it to court are often drawn out for so long that many families give up. Or they end up settling for compensation.

The hard-fought battle against the sheikhs by the families in our film is the exception, not the rule. Many families genuinely believe that the sheikhs want what’s best for their students, and if “mistakes” happen, it’s God’s will.

My own family share these beliefs and I had to keep my investigation secret from them. This was particularly difficult when I visited a khalwa in our home town in North Darfur, where many of my relatives still live.

After the film was aired, I was kicked out of the extended family WhatsApp group. I thought they would at least want to ask me questions or debate with me, but instead they treated me like a stranger. But I got calls from my parents, who told me they would support me, although they were very worried about my safety. I was relieved that my family was so understanding.