When Angelina Namiba was diagnosed with HIV in 1993, the virus was commonly believed to be a death sentence. “People were being told they had six months to live,” says Namiba, who is 55 and lives in east London.

Thinking that if she was going to die, she may as well take a job to keep her busy, Namiba began working for a health authority. In her spare time, she volunteered for an HIV charity.

Twenty-nine years later, Namiba is very much still here, and continuing her work. In 2016, the mother of one helped found the 4M Mentor Mothers Network, which trains women living with HIV to mentor mothers with the diagnosis across the country.

In her work, Namiba draws on her experience of having her daughter in 1998. “I was lucky,” she says. “By the time I had my child, we had effective antiretroviral treatment, which meant I didn’t pass the virus on to my daughter, or partner.”

But no pregnancy is without anxiety – and an HIV-positive pregnancy doubly so.

“Pregnant women are worried not only about their own HIV but also how the treatment will work for the baby,” says Namiba. Through the network, new mothers can “speak to other women who have walked in their shoes and can support them on the journey”. (Today, 99% of HIV-infected pregnant women who follow a treatment plan will not pass it on to their babies.)

“Angelina is an incredible woman who makes real lemonade out of lemons for all around her,” says Alice Welbourn, who is part of the network. “She is a true leader and immensely loved and respected by all of us. I would just love the wider world to know what an amazing woman she is.”

Namiba’s programme is led by Black women from migrant and refugee backgrounds. In addition to supporting women through their pregnancies, the mentors help them to come to terms with their diagnosis.

“Sometimes women may be diagnosed for the first time in pregnancy,” Namiba says. “Sharing that with their significant others can be an issue. Women who are in abusive relationships may have to contend with their partners telling them that no one else will want them, and using that as a form of control. Others may have mental health problems that are exacerbated by the diagnosis.” Namiba and her fellow mentors help them to understand how to ask for mental health support, start their treatment, deal with side-effects and communicate with healthcare professionals.

4M Mentor Mothers also runs workshops to undercut the stigma around people living with HIV. “We don’t accept the negativity with which people tend to portray us,” says Namiba. “Someone living with HIV is a regular person.” She explains that asking people how they contracted the virus can be a loaded question. “People want to put you in a box, and see whether you did someone ‘wrong’. For me, what is much more important is how I live with HIV.”

She says she is open about her diagnosis because “it’s important to have visible people out there. I’m not saying that everyone has to be out there. I know people who’ve been thrown out of their homes because of their status. But people who are able to do it, should. So we can show the world that people living with HIV are regular people. This stigma is killing people. It prevents them from testing and accessing treatment, and staying on their treatment plans.”

A lot has changed since Namiba was diagnosed. HIV is no longer understood to be a death sentence. But there is still much to be done. Most women and heterosexual men living with HIV in the UK are diagnosed late, sometimes after their immune systems have become damaged. “Anyone can be affected,” Namiba points out.

When I ask Namiba what she’d like as a treat, she tells me how reading novels got her through a recent bout of ill-health. She enjoys books by African writers, and stories set in Africa. “They’re such a great way of escaping,” she says. Her favourite author is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The Willoughby Book Club has provided her with a regular selection of handpicked books tailored to her reading habits.

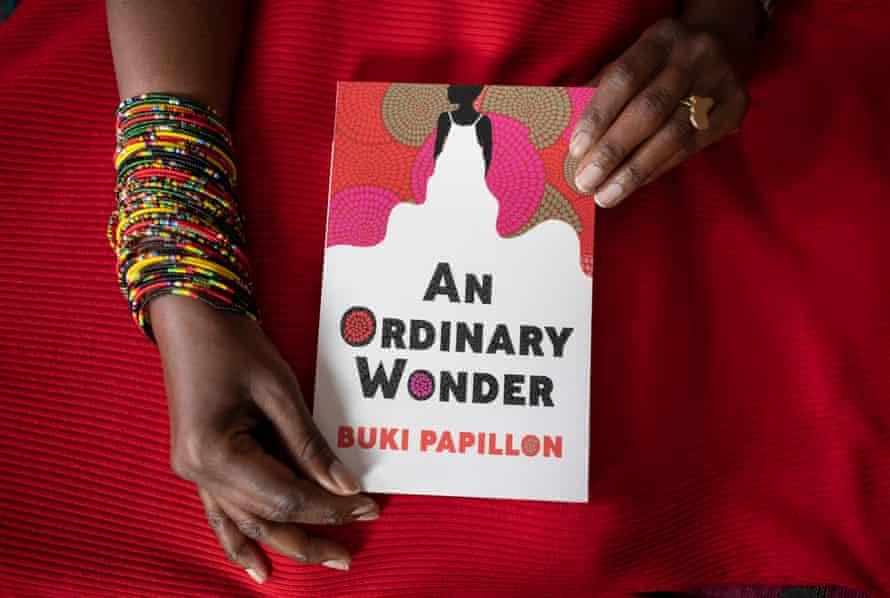

Her first book, An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon, promptly clatters through her letter box, and, when we speak, Namiba is about to dig in. “I’m really delighted,” she says, “because now I have a lot of African writers at my fingertips and I don’t even have to look for them! The books will be suggested for me. I’m really looking forward to enjoying my treasure trove.”