When Sylvie Vernyuy Njobati saw the sacred statue of her Nso people for the first time, she was shaking.

“It was emotional because I was seeing… our founder… our mother locked up in some glass container. And for 120 years, she’s been yelling out. She needs to be back home,” she told the BBC’s The Comb podcast.

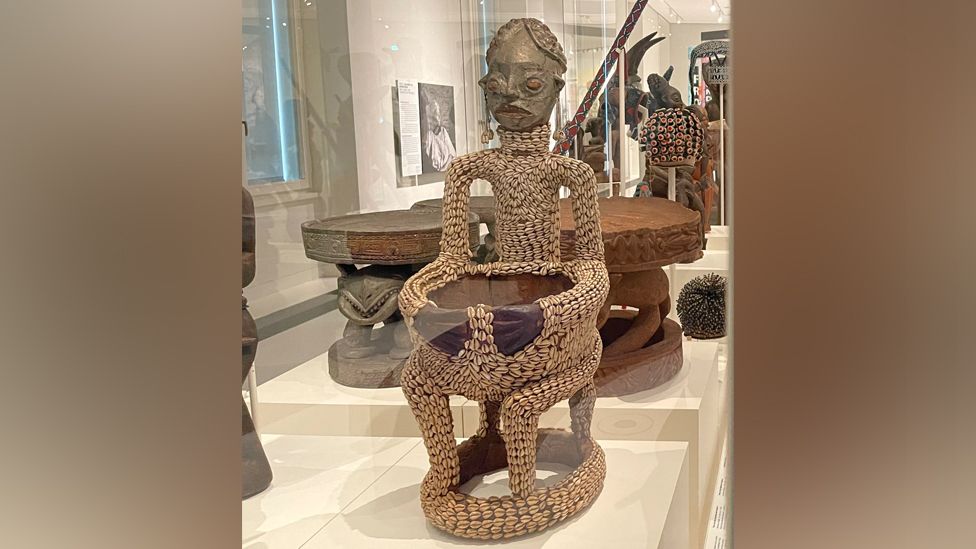

The centuries-old statue – known as the Ngonnso – was on display in a museum in the German capital, Berlin, thousands of miles away from “home” in Cameroon.

It had been in Europe since it had been taken by a German colonialist at the beginning of the last century.

In 2018, Ms Njobati made a promise to her grandfather – to bring back the Ngonnso, which embodies the history and identity of her people.

Three years later she was face-to-face with Ngonnso, a wooden carving less than a metre in height and covered in sea shells. But the effigy was in a glass cabinet.

Her journey to try and fulfil the pledge to her grandfather would take her across continents and ultimately change her life.

It was also a quest that would serve as an inspiration for others working for the return of artefacts looted in the colonial era.

Ms Njobati’s mission to bring back the stolen statue began after she moved from Cameroon’s English-speaking North-West region to attend university in a French-speaking area of the country,where sharp divisions remain between those areas which were part of the British and French empires.

She says the move was a difficult one and she struggled to assimilate. She felt that she did not fit in and yet she was in her own country – the fracture that she experienced was defined by colonialism.

Ms Njobati said she began to examine who she really was, after stripping “off all the colonial cultures, all the colonial legacies that I have inherited”.

Faced with her own identity struggle, Ms Njobati returned home to seek advice from her grandfather, who had experienced his own identity crisis.

It turned out that he regretted not embracing his Nso heritage and choosing to become a Presbyterian pastor rather than a community leader.

“I saw someone also who feels disconnected from his own identity and his own culture.”

Her grandfather not only expressed sadness about what he had lost but also what the Nso had lost both culturally and materially, including the Ngonnso.

According to Nso tradition, Ngonnso was the founder of their kingdom, which dates back to the 14th Century.

Following her death, her statue took on great significance. It was seen as a cultural cornerstone for the Nso.

In 1902, the Ngonnso was taken by German colonial officer Kurt Von Pavel and donated to Berlin’s Ethnological Museum.

Despite various requests to have the statue returned, the Ngonnso has been in Germany ever since. Ms Njobati recalls her grandfather expressing his desire to see the statute returned to Cameroon.

“He clearly mentioned to me that he wishes that Ngonnso should come back, so that he can see Ngonnso at least before passing on.”

It was then that Ms Njobati made her promise to bring back the statue – not only for her grandfather but also as a way to reconnect to her Nso heritage.

She began by researching all she could about the Ngonnso and the previous unsuccessful efforts to have her returned. Over the years, various letters had been sent to the German authorities.

“The Nso people didn’t really know whom they were talking to. They would just sign letters to anyone in a position to help,” she said.

Ms Njobati decided to take a different approach.

“I thought to myself: ‘Restitution is part of a bigger conversation, confronting the colonial past.’ How about we have these conversations as loud as these crimes were committed?”

She started with what she called a “grassroots awareness campaign”. She held meetings in community halls and churches and met people one-on-one.

She also marshalled the power of the hashtag #BringbackNgonnso online.

Through Twitter, Ms Njobati was able to make contact with the Ethnological Museum where the statue was held.

In 2021, when she learnt that the Ngonnso was to be displayed at a new museum, the Humboldt Forum, Ms Njobati flew to Berlin to protest outside, together with a number of other activists.

It was during this visit that Ms Njobati was able to see the Ngonnso statue for the first time.

By this time the campaign to bring back the Ngonnso was gathering steam both online and offline.

Award-winning Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche was among those speaking out about the Ngonnso, and the plight of the Nso.

Ms Njobati’s activism was paying off.

A meeting was arranged with her and Hermann Parzinger, president of The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, a body that oversees 19 museums and collections including the Humboldt Forum.

During that meeting Ms Njobati handed him a restitution request.

That conversation was especially difficult for Ms Njobati as she had learnt that same day that her grandfather had passed away without seeing the Ngonnso returned.

“When I received the call from my mother, my heart sank into my stomach. I was like, not now, we are this close, just hold on. It just got me really, really broken.”

Despite struggling to come to terms with the loss of her grandfather, Ms Njobati felt compelled to continue her campaign.

In the months to come, things began to slowly shift.

For years, the museum had insisted that the Ngonnso was their legal property but now they issued a statement acknowledging that it was taken under violent circumstances.

It was a step in the right direction.

Ms Njobati was then told that a decision about the Ngonnso was imminent. She flew back to Germany and learnt that after 120 years, the statue was to be finally returned.

For Ms Njobati, the decision was an emotionally charged moment.

“I was like: ‘Finally, this is happening. Not just for me, for the Nso people, for Cameroon, and for all of Africa.’ I cried.”

Looking back, Ms Njobati says her interactions with the German authorities helped shape her campaign.

“It’s a tough discussion for the people we now call the perpetrators, because also these people didn’t commit the crimes themselves. And sometimes, we can be very hard on them.

“I made up my mind that I’m going to approach people as human beings first, and then as the institutions they represent second. And I think that worked really well.”

Although a date is yet to be set, plans are now under way for the Ngonnso to be returned.

Ms Njobati sees this as a personal victory and also a wider one for her country and the continent.

“I think that this is a big win for Cameroon as a whole, because this also lends a hand to other communities that are seeking restitution.”

Ms Njobati says that the campaign to bring the Ngonnso home has not only helped her fulfil her promise to her grandfather but it has also brought her closer to her Nso heritage.

“I feel very fulfilled. I’m able to even find closure with the fact that I lost my grandfather. I feel at peace with myself.”