Yassin Fatty, a traditional practitioner of female genital cutting in the West African nation of Gambia, became the first to be convicted there. But her case led to a backlash and a popular campaign to make it legal again.

There were young girls, sitting nervous and excited in new clothes under the afternoon sun. There were musicians, dancing and plates of food. There were old handmade knives and bright new razor blades.

For the 30 traditional practitioners of female genital cutting, who swayed to somnolent melodies in their matching print dresses, the event was a little like the mass cutting parties that they and their ancestors had held for centuries, in the forests of the tiny West African nation of Gambia.

These women were prominent practitioners in their communities, and cutting girls provided them with an income and respect.

But this party, in 2013 in the town of Wassu, signified the renunciation of their calling. The women carried signs that read: “I have stopped female genital mutilation,” below a drawing of a girl’s tear-stained face. One by one, they stepped forward and swore never to cut a girl again. One by one, they dropped their knives and razor blades down on a red cloth embroidered with cowrie shells.

For these women, it was the end of an ancient, socially important, and to many, horrific practice.

Or was it?

One of the 30 cutters present that day, a grandmother named Yassin Fatty, would over a decade later become the first Gambian cutter ever to be convicted of female genital mutilation.

Gambia passed a law banning the practice in 2015, but for years, the law was not enforced, and many Gambians continued to support it. When Mrs. Fatty was arrested for cutting girls and convicted last year, there was a nationwide backlash against the law.

Then Mrs. Fatty got caught between two men: a celebrity imam who wanted to make cutting legal again, and an anti-cutting activist with perhaps mixed motives.

A veteran cutter

We traveled to rural Gambia in July to meet Mrs. Fatty. We found her napping, at noon, on a mat in the shade in her family homestead in Bakadaji, the village she was born in. At 96 years old, she had earned the right to nap. For decades, she was her family’s mainstay, growing all the rice they ate and keeping her sons, their wives and their brood of children in line. But now she was tired, and her legs hurt.

We moved to a room to talk, her son and grandsons sitting around us.

“Now, my only job is to eat,” she said, her eyes twinkling. Then she turned to Mariama Souso, her adopted daughter, and inquired when her next meal would be.

Girls have always been cut in Bakadaji, a tight-knit village in Gambia’s Central River Region where teens sit under trees trying to load their WhatsApp messages, men zoom off on their motorbikes to go fishing, and the muezzin calling the faithful for afternoon prayers, despite his valiant efforts, often manages to attract only a knot of old women.

And for decades, Mrs. Fatty — whose age is apparent not in her barely wrinkled skin but in her earlobes, split and scarred from long-departed earrings — was the one who cut them. Thousands of them.

“We found the practice here,” she said. “Our parents did it.”

She always cut the girls in an outdoor bathroom, she said, and immediately after, brought them to the rough-walled, unpainted room we were sitting in. We looked around. Worn fabric hung from the entrance in place of a door. The only furniture was a simple wooden bed and a bench covered in a piece of cloth, embroidered with the words “I love you.”

In Gambia, female genital cutting usually means removing the clitoris and part of the labia minora, and sometimes sealing the vagina shut except for a tiny hole. To outsiders, it seems unspeakably cruel.

But many Gambian villagers see girls who are not cut as unclean, and unreligious. These girls often become social outcasts. No man will marry them. Nobody will eat their cooking.

But Mrs. Fatty believed that the consequences of not being cut went much further than that. She asserted, against all medical evidence, that by cutting girls, she was also protecting their health. Uncut women are more likely to suffer and die in childbirth, she said, and are more likely to get sexually transmitted infections. (The opposite is true.) And then there was the sexual desire of women who still had clitorises, which many people in Bakadaji thought was a huge problem.

“If a woman is not cut, she’s always ready for sex,” Mrs. Fatty said, with a hint of a smile. “She can do it from morning to night.”

From his spot on the packed dirt floor, one of her grandsons, 24-year-old Abdoulaye Cham, piped up. Cutting girls prevented them from cheating on their husbands, he said. “A lot of young men travel and leave their wives here,” he added.

Another grandson, 23-year-old Masanneh Cham, dressed in skinny jeans, put forward a different argument, one espoused by several influential imams and their flocks, and spread on Facebook and WhatsApp.

“Whoever fights female circumcision is fighting God,” he said.

The lion man of Gambia

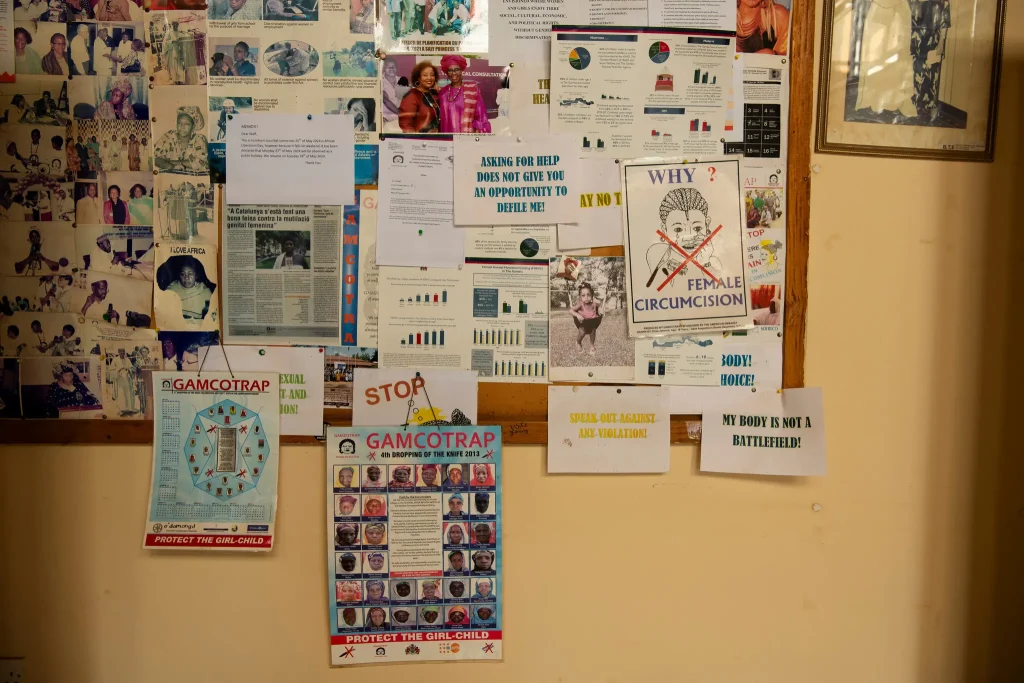

When Mrs. Fatty’s grandson cast opponents as godless, he had someone in mind. This was Momodou Keita. Mr. Keita was a heavyset, often affable man in his 50s with a liking for Coca-Cola, known for his decades fighting female genital cutting. He zoomed around the Central Rivers Region on his motorbike, persuading cutters like Mrs. Fatty to stop, and take part in the dropping-the-knife events held by the organization he worked for, the Gambia Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, known as GAMCOTRAP. In a series of evening interviews at our guesthouse, he told us how he worked.

He had signed up hundreds of cutters over the years, he said, pulling posters featuring their faces, like mug shots, from a leather folder he always carried. Each woman was given money to start a business, as an alternative income source. Mrs. Fatty got cash to start a bakery, operated by her youngest son, which made the family good money, especially during the holy — and carb-heavy — month of Ramadan.

Before she attended the dropping-the-knife ceremony, Mrs. Fatty was shown a video about the consequences of cutting for women’s health. She attended a few days of an awareness-raising program on cutting organized by GAMCOTRAP, with the blessing of Bakadaji’s village chief. But beyond that, there was little attempt to change her mind.

After he recruited and educated the women, Mr. Keita had informants keeping tabs on each of them. He was proud that none of the women, according to him, had ever gone back to cutting — and took much of the credit.

“I am the lion man of The Gambia!” he said in one of our interviews, after detailing his credentials in the fight against cutting. “I am the gorilla of The Gambia!”

He and Mrs. Fatty had, in the years since her renunciation ceremony, struck up an unlikely friendship. Mr. Keita often stopped by her house. He shot the breeze with her and her sons. He drank glass after glass of attaya — sweet, frothy green tea.

“It was just casual chat, he never asked about circumcision,” Mrs. Fatty said. “I even gave him chickens, sometimes.”

But then, in late 2022, Mr. Keita said, his informants told him something was brewing in Bakadaji. Mrs. Fatty was going to cut eight girls, they said. He immediately drove to her home, he said, to warn her not to proceed.

“Proper monitoring is on you,” he remembered telling her. “You will be arrested.”

“She said, ‘Me? I will never ever do it,’” he recounted.

But on Jan. 16, 2023, an informant called again. The cutting was going ahead that morning, the informant said. Mr. Keita jumped on his motorbike.

When he arrived at Mrs. Fatty’s home, babies were screaming inside.

He had come too late. Mrs. Fatty had already cut two baby girls. He saw a woman running across the field away from the house, a third baby in her arms, but he couldn’t catch her.

He turned to Mrs. Fatty.

“I told her, for these girls, this thing will not end between us,” Mr. Keita said.

Then Mr. Keita called the police.

Cutting in secret

As the moon rose one evening, we walked through Bakadaji’s alleyways, stopping at two family homesteads full of children and young teens playing raucously, eating dinner, cuddling with their fathers and disappearing into clouds of soapsuds as their mothers washed them before bed.

Even after the dropping-the-knife ceremony, Mrs. Fatty had secretly cut girls, she and family members told us. Over the years she had cut every girl in these two homesteads, their parents explained, except one — a 2-year-old girl named Nyara Kebbe, who played quietly in a pink bathing suit. This was the girl who Mr. Keita had seen in the arms of her fleeing mother but was unable to catch.

Mrs. Fatty had been given a bakery to lure her away from cutting, which, it was assumed, she practiced for the income. But Mrs. Fatty said that for her, cutting was a belief, and the threat of prosecution meant little to her.

“Even if you bring a bag of money, I won’t stop what I found my grandparents doing,” she said. “I don’t do anything just because I’m told to by outsiders. I listen to myself.”

And she claimed that although she’d attended the 2013 dropping-the-knife ceremony, she didn’t drop her knife or make any vow — a claim contradicted by GAMCOTRAP staff who were there.

Experts say that many practitioners are now cutting in secret, and cutting younger girls, who are less likely to remember. In 1991, Gambian girls were cut on average at age 4; now, they are usually under 2, U.N. estimates show.

Despite the millions of dollars spent by U.N. agencies and American and European donors on programs to curb cutting in Gambia over the past three decades, and even though it has been illegal to cut girls since 2015, there has been almost no change in the rate of cutting, which stands at 73 percent of girls ages 15 to 19.

Dramatic change takes decades, said Claudia Cappa, UNICEF’s lead expert on global trends in cutting. “It’s a social norm. It links to identity, it links to sexuality,” she said. “These things don’t change overnight.”

Gambia’s first convicted cutter

When the police arrived, they arrested Mrs. Fatty along with the mothers of the two babies Mr. Keita found, screaming and bleeding, in her house. The babies were treated in the hospital and slowly healed, though the permanent damage was done.

The whole family was worried about Mrs. Fatty, who was released on bail but was bewildered, and could barely manage the arduous motorcycle trips to report at the police station.

And they could not believe how, in their view, Mr. Keita had turned on them.

To the outside world, Mr. Keita looked heroic — the man who had dedicated his life to fighting cutting, who dramatically caught Mrs. Fatty in the act, and thus, according to him, saved several girls from being cut.

But Mrs. Fatty and her son Abdou Cham now say that Mr. Keita was a fraud. He never cared about cutting or protecting girls, they said, and told them to take the money from the Westerners who funded GAMCOTRAP while doing as they pleased — something Mr. Keita denied.

“Circumcision cannot be eradicated in this area,” Mr. Cham remembered Mr. Keita telling his mother. “You can do this in secret. Nobody will find out.”

The way they saw it, Mr. Keita was interested in nothing but money — and that was why he had latched onto a Western-funded organization campaigning against cutting.

At the police station, as Mrs. Fatty waited to be booked, Mr. Keita confirmed their suspicions, Mr. Cham and two male relatives said. He approached them, they said, telling them he could “kill the case” in exchange for a bribe. They complied, and gave him money then and more two weeks later — a total of 5,500 dalasi, about $80, they said. Mrs. Fatty’s adopted daughter and devoted caretaker, Ms. Souso, said she saw the money change hands.

In an interview, Mr. Keita vehemently denied soliciting or taking any bribes.

But an official familiar with the case, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid reprisals, confirmed the family’s account.

Mr. Keita was charged with obtaining money under false pretenses, but the charges were later dropped. Mrs. Fatty’s family was advised to bring a civil suit instead, as the police did not consider the matter to be a criminal one, according to the official familiar with the case.

And Mr. Keita did not kill the case. That August, Mrs. Fatty and the two mothers stood trial. All three pleaded guilty. All three were convicted and fined 15,000 dalasi each (about $215).

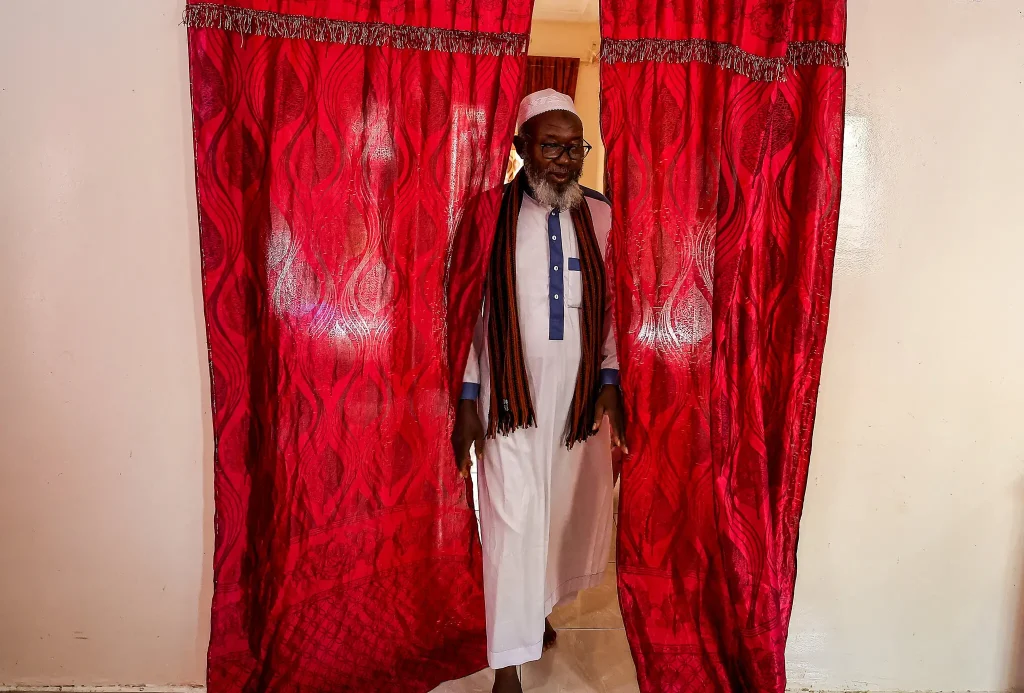

The celebrity imam

The costs of the whole affair — the fines, the alleged bribes, and the gas costs of traveling to and from the police station and court — almost bankrupted Mrs. Fatty’s family members, who mostly work as subsistence farmers.

But the trial also attracted the attention of a powerful distant relative.

Abdoulie Fatty, one of Gambia’s best-known imams, was outraged when he heard what his 96-year-old cousin had been subjected to.

The right of Gambians to cut girls was a cause Imam Fatty had long and loudly espoused. He falsely claimed that female genital cutting carries no health risks. He called those trying to stop it enemies of Islam. And he accused the West of imposing its culture on Gambia.

With several Gambian lawmakers, he started campaigning in earnest for the country’s Parliament — or its Supreme Court — to decriminalize cutting, using Mrs. Fatty’s travails as a rallying cry.

The resulting national debate sometimes verged on culture war, and had some surprising effects in conservative Gambia, which is 96 percent Muslim. In urban areas, people were suddenly speaking openly — in person and online — about clitorises and women’s sexual desire.

Imam Fatty himself went on a talk show on Kerr Fatou, one of Gambia’s best-known websites, to suggest that men rub their wives’ nipples as an alternative to clitoral stimulation.

In villages like Bakadaji, and families like Mrs. Fatty’s, steeped in tradition, Imam Fatty’s message added to the impression that cutting was sanctioned by Islam — something many Muslim clerics and scholars say is not true.

The imam changed the financial fortunes of Mrs. Fatty’s family.

He visited her in Bakadaji, paid all three women’s fines, and relayed donations from some of his followers in the United Kingdom, which they used to build a cinder block wall around the back of the homestead, where Mrs. Fatty usually cut girls.

The support of such a prominent figure emboldened Mrs. Fatty. But her arrest and trial had weakened her, and though she talked a good game, her family doubted she would ever have the strength to cut again.

It would be the end of a long era. Mrs. Fatty inherited her vocation from cutting practitioners on both her mother’s and her father’s side.

Now, she said, “I’m the only one left.”

But she confided something before we left Bakadaji, as evening deepened, as men came back from fishing.

She pointed to Mariama Souso, her adopted daughter. She has chosen her as her successor.