The psychological effects of going deaf as a child were unbearable. But after stumbling across a front-page headline, reading the news helped me discover new worlds

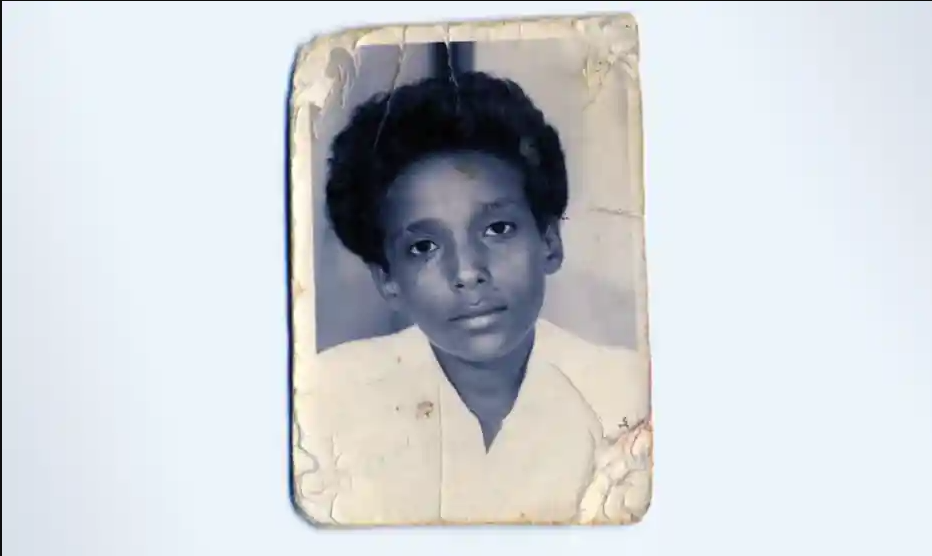

It was a long time ago, on a Friday afternoon, on a street in Khartoum. I was 11 years old, or perhaps 12 – I don’t know the date or year I was born. I was feeling very sad. I had spent the whole night before crying and shouting because a doctor had just told me that I’d never regain my hearing and prescribed a hearing aid. “Why me?!” Up until that moment, I’d had a faint hope that I would be treated in the capital and be able to hear again.

I had lost my hearing completely in my left ear and about 80% in my right ear, but this makes it appear better than it was: as a doctor once put it to me, I would just about be able to hear the roar of an aeroplane engine without my hearing aid if I stood next to it.

My hearing went after I fell ill with meningitis. We were living in Wad al Hulaywah, a village in Sudan, although I was born in Omhajer, Eritrea. After my father’s death, my mother, sister, brother and I were forced to flee the war of independence against Ethiopia. The village in Sudan had been turned into a makeshift refugee camp for Eritrean refugees.

The only doctor in Wad al Hulaywah was away on holiday, so a nurse tended to me. He mistakenly thought I had malaria and treated me as such. My pain got worse and worse until my family took me to a nearby village, Showak, a few hours’ drive away, where there was a Red Cross hospital. Since I couldn’t move, I travelled on my bed, which had been put in the back of a Jeep. When we arrived at the river crossing, I was moved to a boat, still in the bed, crossing the Setit, one of the branches of the Nile.

At the hospital, I was diagnosed with meningitis and admitted. By that time, I was unconscious. I remained in a semi-coma-like state for three weeks. When I woke up, the first thing I said was that I could not hear.

Back in Wad al Hulaywah, I saw traditional healers to no avail. I saw fortune tellers who predicted I’d hear again within a year. My mother hurried back from Saudi Arabia, where she worked, and took me to Khartoum to see an ear specialist. There, we stayed with some relatives, but even though they took me on shopping trips and strolls, I felt alone.

On that Friday in Khartoum, I was walking aimlessly down the street. I stopped at a newspaper vendor. The papers were arranged neatly on the ground, with a stone on the top of each paper. I bent down to read the headlines.

And then I bought my first ever newspaper. But why a newspaper? I don’t know – but I immersed myself in every single piece of news. Over the next few days, I bought lots of newspapers, so I could take them back with me to the village. In Wad al Hulaywah, there were no books. No libraries. No bookshops. No news vendors. There were barely textbooks in our school.

The psychological effects of deafness were unbearable. Initially, it was like a visible disability – I was popular in my neighbourhood and beyond as a hot-headed kid, and everyone talked about my hearing loss. But as time passed, they forgot about it, and it became an invisible disability. I hardly got any help.

But that moment with the newspapers transformed me from feeling sorry for myself, which I did for a long time, to finding ways to cope, showing me how to live in my inner world as well as the outer one. From that moment, I knew about another and faraway world, a world other than my immediate surroundings, I knew about its conflicts, sports and entertainments.

My analogue hearing aid was nothing but a loud microphone. Still, I went back to school. I didn’t hear much in the classroom, if anything at all. I pretended to hear. Sometimes, I said “yes” or “no” to whoever was talking to me. It was possible that I said yes or no to someone who asked me what my name was. And sometimes, I talked and talked as if not wanting to forget my ability of speech. I also became the best in my class in reading and writing.

Although I had no friends when my mother took us to Saudi Arabia a few years later, some students in my class became friendly with me so I could help them with their coursework or to cheat in exams. When I read, I concentrated on opinion pieces or regular columns by writers who always referred to European or American writers and thinkers you probably wouldn’t find in most Saudi bookshops. For a long time, I went to bookshops to see books, check names and titles. Soon, I had immersed myself completely.

When I arrived in the UK, I spoke no English at all apart from a few words, and had a knowledge of the alphabet. The next day, I saw someone reading the Sun. The headlines were in a large font. I tilted my head. I read slowly, letter by letter. I remembered that moment, that Friday afternoon, again. Since I knew I couldn’t rely on my hearing aid to learn the new language, I knew at once how I would start learning again.

The short story collection The Feeling House by Saleh Addonia is out now, published by Holland House.