“First we were enslaved. Then we were poisoned.”

That’s how many on Martinique see the history of their French Caribbean island that, to tourists, means sun, rum, and palm-fringed beaches. Slavery was abolished in 1848.

But today the islanders are victims again – of a toxic pesticide called chlordecone that’s poisoned the soil and water and been linked to unusually high rates of prostate cancer.

“They never told us it was dangerous,” Ambroise Bertin says. “So people were working, because they wanted the money. We didn’t have any instructions about what was, and wasn’t, good. That’s why a lot of people are poisoned.”

He’s talking about chlordecone, a chemical in the form of a white powder that plantation workers were told to put under banana trees, to protect them from insects.

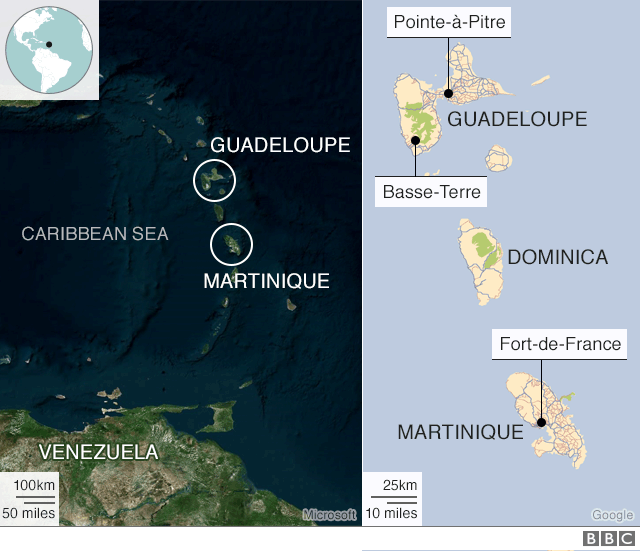

Ambroise did that job for many years. Later, he got prostate cancer, a disease that is commoner on Martinique and its sister French island of Guadeloupe than anywhere else in the world. And scientists blame chlordecone, a persistent organic pollutant related to DDT. It was authorised for use in the French West Indies long after its harmful effects became widely known.

“They used to tell us: don’t eat or drink anything while you’re putting it down,” Ambroise, now 70, remembers. But that’s the only clue he and other workers in Martinique’s banana plantations in the 1970s, 80s and early 90s had about the possible danger. Few if any were told to wear gloves or masks. Now, many have suffered cancer and other illnesses.

Chlordecone is an endocrine disrupter, meaning it can affect hormonal systems.

Following a detailed study of one of the world’s expert on Chlordecone, Prof Luc Multigner and colleagues conducted on Guadeloupe in 2010, he estimates chlordecone is responsible for about 5-10% of prostate cancer cases in the French West Indies, amounting to between 50 to 100 new cases per year, out of a population of 800,000.

Chlordecone stays in the soil for decades, possibly for centuries. So more than 20 years after the chemical ceased to be used, much of the land on Martinique cannot be used for growing vegetables, even though bananas and other fruit on trees are safe.

Rivers and coastal waters are also contaminated, which means many fishermen cannot work. And 92% of Martinicans have traces of chlordecone in their blood.

Ambroise, who worked with chlordecone for so many years, had an operation to remove his cancer in 2015. But he still suffers from thyroid disease and other problems that may be connected to chlordecone’s known effects on the hormonal system.