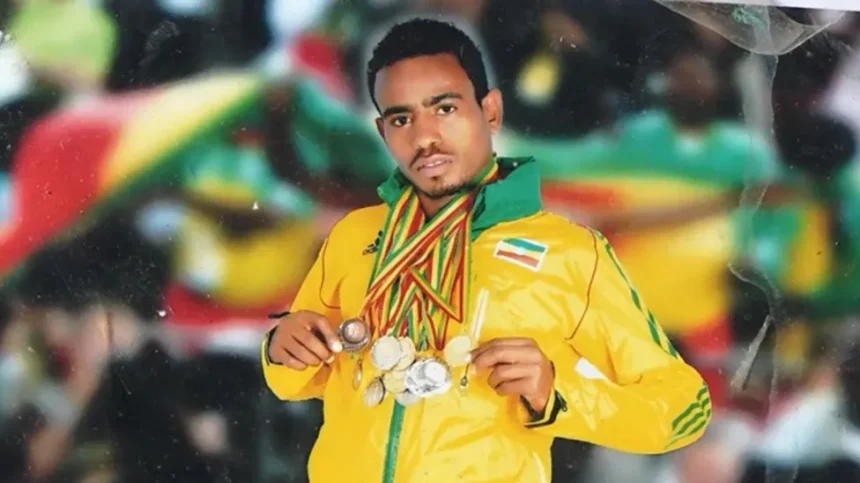

Redae Gebreyesus could have been representing Ethiopia at the Paris Olympics, but his life was cut short by civil war.

The talented middle-distance runner was killed in late 2020, not long after the conflict in Tigray broke out in November of that year.

Tigray, the East African nation’s northernmost state, has always been a vital part of Ethiopian athletics, with a third of the country’s track team currently competing in the French capital hailing from the region.

According to his coach, Gebreyesus had the potential to be part of that squad – had it not been for the bloody two-year battle between Ethiopia’s government and forces in the region.

“Redae, without any doubt, wouldn’t have just been selected but he could have won medals,” Getye Mekuria told BBC Tigrinya.

“He could have been better than the rest of the athletes. His death is considered as Ethiopia losing one eye.”

Fighting ended when the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front signed a peace deal brokered by the African Union in November 2022.

But a study by Ghent University estimates that up to 600,000 people have died because of the war, with over two million displaced and nearly 900,000 forced to flee as refugees.

In the town of Edaga Arbi, some 25km from the border with Eritrea, Gebreyesus’ mother still mourns the loss of her son.

“I lost everything,” said Hadera Seyum from her home.

“However, I have his children. Had he had no children, I would have considered myself as having nothing.”

A potential ‘icon’

Gebreyesus trained at Tigray’s main athletics facility in Maychew and won medals competing across the region.

He was inspired by Hagos Gebrhiwet and Letesenbet Gidey, fellow athletes from the region who have won bronze medals at the Olympics over 5,000m and 10,000m respectively.

“I remember he started (training) in 2006,” said his teary-eyed mother.

“He would run right after school before he came home. He’d also wake up early in the morning to train.

“He said he would reach the highest level. He promised he would change his family.”

Gebreyesus, described as a respectful family man who worked in construction and could craft pieces of farming equipment out of metal, was at home when soldiers attacked his village on 19 November 2020.

As his mother and sister ran away, he stayed behind to help the Tigrayan forces defend their land.

That was the last time his family saw him.

Gebreyesus’ widow, who met her husband through athletics before they were even teenagers, now cares for their children and her mother-in-law.

“He would have been an icon to his country,” said Timnit Aregawi.

“He was brave, not only for his family. He means everything to me.

“I am almost not alive after his death.

“I’m exposed to disease and problems. I’m psychologically damaged, I’m traumatised.”

Military casualties

The fighting may have ended more than 20 months ago but the emotional and physical impact of the Tigray war, which caused famine-like conditions, is still clear across the region.

Like every part of life, sport was affected, with $1.7m (£1.35m) worth of damage estimated to have been done to training facilities.

The head of the state’s athletics body says the conflict has claimed the lives of around 100 athletes, coaches and administrators.

“Many of them would have reached international competitions,” Kidane Teklehaymanot told the BBC.

“They could have been a source of economy for their families and their country.”

Teenager Belaynesh Yaya was another athlete who had a bright future on the track.

Her brother Habtamu Yaya described athletics as a “culture” in their district, Endamekoni, explaining that Belaynesh “learned it from her ancestors”.

“I strongly believed she could represent her country,” he said.

“She would have made the team for the Olympics this year. My dream was to see her in international races.”

The 18-year-old hoped to emulate Ethiopian Olympic champions Meseret Defar and Haile Gebrselassie, but reality sent her in a different direction.

Needing money before the conflict broke out, she joined the regional military – against her father’s wishes.

“I was not happy,” said Yaya Gebresamuel.

“How could a father allow his child to enter into a fire? I strongly preferred to see her in athletics than the military.”

She was involved in fighting around her family’s home village and told her father that friends of hers had died.

“I insisted on pulling her out but she’d rather die than retreat,” Gebresamuel recalled.

“All the family begged her but yet she refused.”

The runner was eventually killed fighting alongside the Tigrayan forces.

Her family are yet to see her burial site.

Back on track

Like Gebreyesus, coach Mekuria also trained Belaynesh Yaya in Maychew.

“She was like my daughter. She was disciplined, she was innocent,” he said.

“They were training intensively day and night. They were hard-working.

“We were not expecting war and not thinking they’d join the military.“

Maychew’s track has helped produce Olympic medal winners for Ethiopia, stars like Gudaf Tsegay, who took bronze in the 5,000m at the 2020 Tokyo Games and is the reigning 10,000m world champion.

Tigray’s next generation of athletes are back training in Maychew, despite the dilapidated condition of some of the facilities.

Huge cracks run along the walls of the training centre and plaster has dropped off many surfaces.

One of the hopefuls who has returned, Fikr Solomon, remembers better days and his friend Redae.

“What made Redae unique was when we woke up early in the morning he started our day with jokes.”

While the long-term impact on Ethiopian athletics remains uncertain, there is no doubting the human cost of the war in Tigray.