When Jerald Walker was a boy, his school principal called him into his office and asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up. “My answer was: ‘A god,’” Walker recalls, laughing. “He thought I was kidding but I was serious. When he asked again I said: ‘Captain Marvel.’ Because I thought about comic book heroes. I couldn’t think ‘doctor’ or ‘writer’ or any of those things. I had never once given any thought to what my adulthood would be.”

Walker wasn’t even sure he’d have an adulthood. He grew up convinced that the world would end in 1972, when he would be eight years old. According to the prophecy, fire and brimstone would rain from the skies, people would be running in the streets in panic, covered in boils, their faces melting. But as members of the Worldwide Church of God (WCG), Walker and his family would be saved – and magically transported to a place of sanctuary, probably Petra, in Jordan. “The bad news was that there wouldn’t be a future, but the good news was: ‘You don’t have to worry about it. Everything is laid out for you.’”

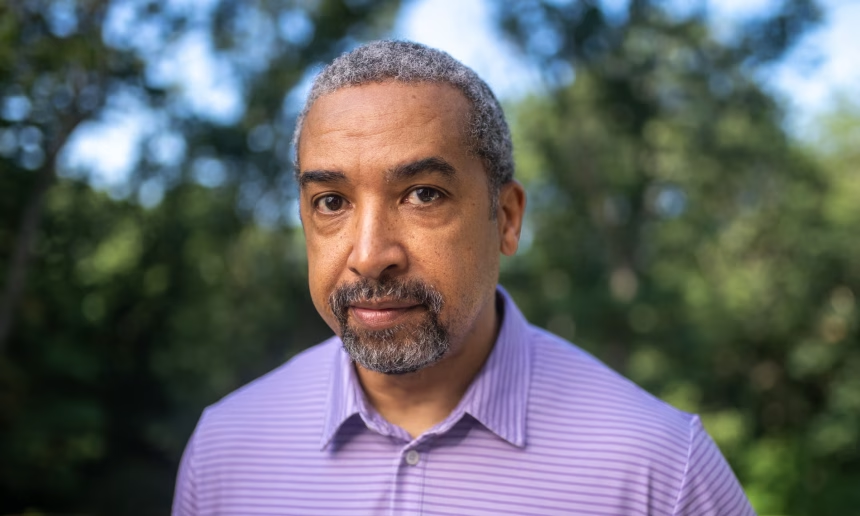

It took Walker, and many others, a while to realise that the WCG was the textbook definition of a doomsday cult. And a white supremacist one at that – which, somehow, his black parents seemed to be fine with. It took even longer for Walker to get over his upbringing and become the writer and professor of creative writing he is today. The experience “ruined my youth”, he says over video call from his Boston home. “We thought we were chosen for salvation, but we were chosen for ruin.”

Walker knew his family was different from the start. “We didn’t celebrate Christmas or Halloween; we didn’t celebrate our own birthdays. Most people we knew went to church on Sundays; we went on Saturdays. We weren’t supposed to socialise with people who weren’t in the church,” he says. “We tried to keep it concealed as much as possible, but it came out in ways that we simply couldn’t prevent.” At school, when other kids were making Christmas decorations in class, Walker and his twin brother James would have to sit by themselves doing something else. “We would say: ‘It’s against our religion,’ which was the phrase we used all the time.” Most children assumed they were Jewish, he says, which was easier than having to explain the truth.

I don’t recall ever wanting to go to church. I would be shaken up for many hours afterwards

“I hated not celebrating these things. My favourite day of the year was the day after Christmas. Because that was the farthest day away from the next Christmas.” Halloween was also painful, because to Walker, dressing up looked like fun, but when trick or treaters came to the door, “my father would wave his Bible and say: ‘This is a pagan holiday and God shall punish you for it.’ The next morning, as was the tradition for people who did not give out candy, our house would be covered with garbage and eggshells from people throwing things at it.”

There was another reason Walker’s childhood was different: both of his parents were blind. His father fell down a flight of stairs when he was 12 and developed a blood clot on his brain, which deprived him of his sight. His mother was blinded in one eye as a baby as a result of folk cures for glaucoma, including cow’s urine and cigarette ash. Then, when she was nine, she was hit in the other eye by a piece of wood and lost her sight entirely.

Both of them led as active lives as possible. They would often rely on their six children to be their eyes – guiding them in the street, helping them to read or choose clothes. Walker’s father worked as a counsellor for people with visual impairments; his mother was not employed, though raising six children was work enough. The family was poor – partly as a result of giving 30% of their earnings to the church – but they were never destitute, he says. When he was six they moved to Chicago’s South Side – then a prosperous white neighbourhood.

Having blind parents did have its advantages. “When we saw an opportunity to get away with something, we did it,” says Walker. “When my mom served vegetables, which we weren’t fans of, we would pretend to eat them but put them in the garbage. But then my mother got wise to that, and after dinner she would reach into the garbage and pull up a handful of carrots and peas and say: ‘OK, who did this?’ So we started dumping our vegetables behind the refrigerator – which was not good because over time that presented some problems too.” His parents had not lost their sense of smell.

Walker’s parents’ blindness and their susceptibility to the WCG were not unrelated, he believes: “One of the benefits of this church was that we were told when Christ returned, the people who were chosen would have their afflictions fixed … If you’re the parents of six children, the possibility of one day seeing their faces is a strong incentive to join any number of outrageous organisations.”

The WCG was founded by an Iowan evangelist named Herbert W Armstrong, who built up his following in the 1930s via radio broadcasts, his magazine, the Plain Truth, and later via television. At its peak the church had more than 100,000 members.

Walker and his family rarely saw Armstrong in the flesh but they consumed his television and radio bulletins weekly. Then there were the apocalyptic, two-and-a-half-hour sermons every Saturday. “I don’t recall ever wanting to go to church,” Walker says. “I recall being shaken up for many hours afterwards. At night, you relive the sermons and the scary things.” And if the sermons failed to conjure up enough terrifying images, the graphic illustrations in WCG’s literature did the rest. “When you’re in a doomsday cult, the main way to keep everybody in line is fear.”

In retrospect, Armstrong’s views on race were no less horrific. “He said that black people were an inferior race to white people, and he cited biblical scripture to prove it,” Walker explains. “He made it quite clear to his converts that white people were made in the image of God, that black people were put on Earth to be their servants, and that heaven would be segregated; even though we were going to be saved, we would not be with white people. We would be sent to Africa or some place.” The WCG was also segregated on Earth. Its membership was more than 90% white, but Walker’s church was all black. Even at mass WCG gatherings, the black congregation would be kept separate from white people. Interracial marriage was forbidden.

“The irony is that even though it was a white supremacist segregationist church, the black people who were chosen felt special,” says Walker. “Even though we accepted our inferiority to white people, because we thought it was biblically ordained, we still, nonetheless, felt that we were superior to other black people.”

Walker vividly remembers the buildup to doomsday: 1 January 1972. The family had been stockpiling tins of food in the basement, just in case their escape to a place of safety was delayed. But when the fateful day arrived, of course, nothing happened. Armstrong sent a newsletter to the congregation. “He said: ‘I never said it definitely would be 1972. The reason why it hasn’t happened is because we haven’t completed our work on Earth yet. God has kept me here because he wants me to spread the word to try to save more people before he returns. I can only spread the word more if I have more money; please send your cheques to …’ And so that’s what we did.”

For the next few years, Armstrong continued to shift the doomsday deadline, taking each global conflict and disaster as confirmation that the end was imminent, “and we would keep waiting for him to be correct. As a kid I was disappointed, but also relieved that he was wrong.”

The breaking point for most came with a 60 Minutes exposé on the WCG in 1979, which detailed Armstrong’s lavish lifestyle, his alleged financial improprieties and a power struggle between Armstrong and his son, Garner Ted Armstrong, whom he had excommunicated (Garner Ted later formed his own church). “We got a really good sense that this was not a legitimate church, that he was not the Messiah, that he was a conman and we were all dupes,” says Walker. He stopped going to church and his parents did not force the issue. They also stopped going shortly after, as did the rest of the family.

Walker’s elder brother Timmy had already checked out a few years earlier. “His view was: ‘The world is full of conmen; we ought to be conmen, too.’ And so he started selling drugs and committing petty crimes.”

Walker followed in his footsteps. At 14, he had been identified as an able student and offered a place at a better school, but to his regret, he had turned it down – half-wondering if it was a trick being played by the devil. At 16 he dropped out of school altogether. “I wanted to fully commit myself to my delinquency,” he says. He began heavily consuming alcohol and marijuana, and later, cocaine. In parallel with his descent, Chicago’s South Side had turned into a crime-ridden ghetto by this time. He was doing menial jobs just to buy more drugs. “I was very, very confused and depressed. For so many years, I had been convinced that I would die and then be reborn. Then to find out: nope, you’re just like everybody else. And now you’ve got to get on with your life. I didn’t know what to do.”

The wake-up call came when he went to buy coke one night from his friend Greg, who had just become a dealer. As he was about to go up to Greg’s apartment, he says, “a figure emerged from the shadows, and a man took a gun out and put it to the side of my head. He said: ‘This is a robbery,’ and he started to frisk me, but the joke was on him. I was there to get drugs on credit. I didn’t have any money.”

He proceeded to score the drugs (this was by no means the first time he’d been mugged). Later that night, back in his own apartment, his brother Timmy called and told him that Greg had been found dead in the alley – doubtless shot by the same man who had attempted to rob Walker. “So there I was, 22 years old, high on the drugs of my dead friend, trying to figure out how I had escaped that fate,” he recalls. “My apartment was on the 16th floor of this rundown building, and I gave serious thought to simply opening the window and pitching myself from it. Instead, what I tossed from the window was the cocaine. I decided that something had to give and I had to do something with my life.”

It was a long, slow journey from there to where he is now. On the train to his menial job, cleaning human waste from test tubes at the hospital, he would see young people getting off at the stop before, which was for the University of Illinois. One day he got up the nerve to follow them. He went into the library, pulled out a book and started to read, “waiting for someone to come tap my shoulder and say: ‘What are you doing in here? You’re one of the followers of the Worldwide Church of God,’ and just kick me out. It didn’t happen.”

He kept on going in and reading. He then applied to enrol but, having dropped out of high school, he lacked the qualifications, so he went to community college instead. When he randomly took a course in creative writing, his teacher told him he had talent and that he should set his sights on the renowned and highly competitive writers’ workshop at the University of Iowa. The teacher, named Edward Homewood, mentored Walker, and even drove him to Iowa to visit the campus. Walker realised he could never afford the tuition fees, but Homewood told him: “‘You just worry about classes. I’ll pay for your degree.’ I was stunned by that.”

Two years later, he was accepted to the Iowa writers’ workshop. As Walker puts it, one elderly white man – Herbert W Armstrong – ruined his life, and another one put it back on course.

Walker’s first book, Street Shadows, chronicling the “thug life” he had lived, was well received, and as a result, he says, people started asking about his earlier childhood. “I spent many, many years avoiding the topic, because I didn’t want to revisit it. But it just so happens that when you’re a nonfiction writer, the material is finite.” His memoir, The World in Flames, was published in 2016. “Revisiting that time was difficult and painful,” he says. “I didn’t like writing the book. I didn’t like reliving any of that. I didn’t like doing the publicity events.”

How does he feel talking about it now? “It’s not painful. It’s upsetting, it’s infuriating. The story I mentioned about not going to a school that could have changed my life in positive ways upsets me. I get upset at my parents, even though I can understand why they did what they did. It angers me to know what happened to my brother Tim.” Tim died of a heart attack aged 47, after struggles with addiction; the rest of his siblings are alive and generally well. His father died aged 65 and his mother died four years ago. “I just think of all the lives that could have been different, better, had we not been chosen.”

Walker’s own life is at least in a good place now: married, with two grownup sons, teaching and writing. He’s come through it, he says, “and the further I get away from it, the better I am”.