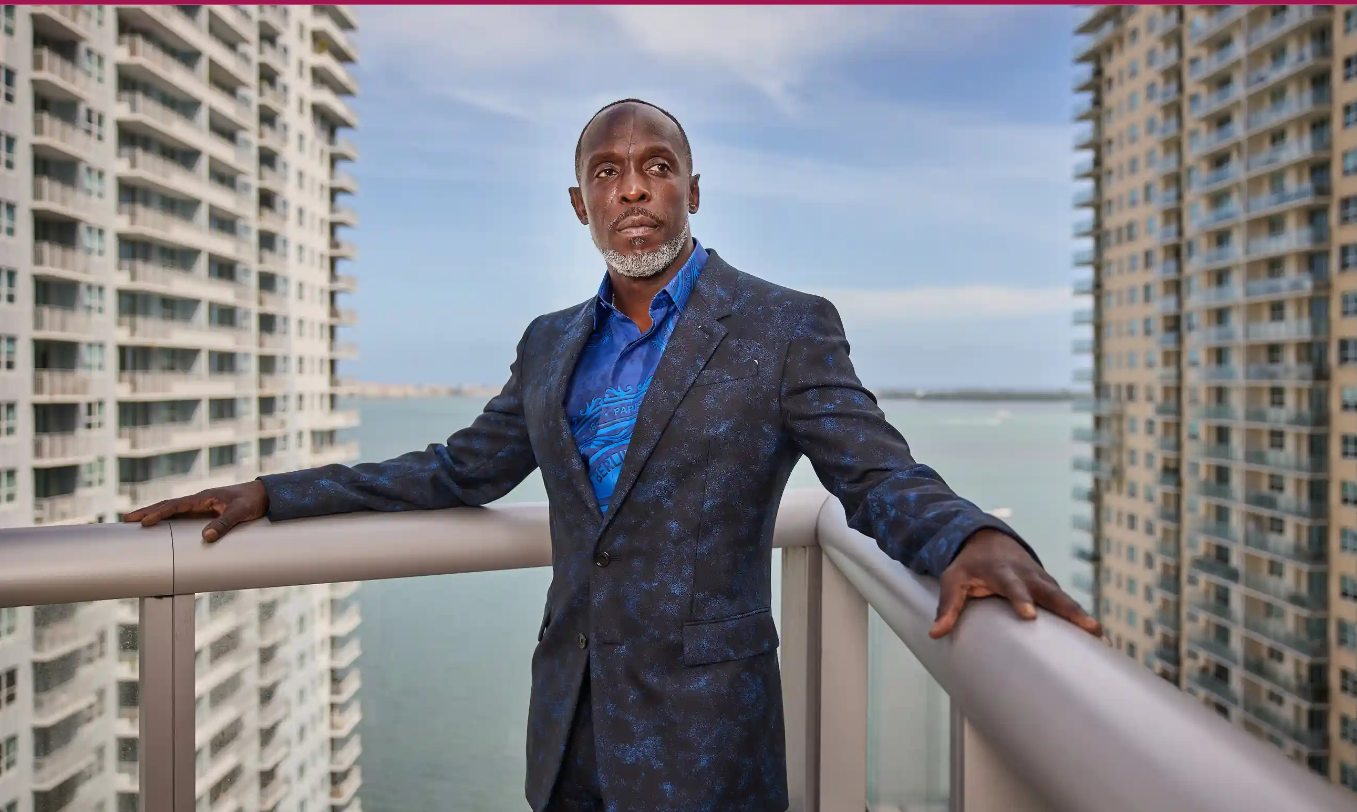

After leaving school, against the wishes of his family, Michael K Williams began working as a backup dancer and model, working with 90s cultural icons including Madonna and David LaChapelle. His film debut came in Bullet (1996) opposite Tupac Shakur, but his real break came when, after a single audition, he was cast as Omar Little in HBO crime drama The Wire …

If it looks real to you, it feels real to me. On The Wire, Omar’s tenacity and swagger were based on people I knew and grew up with – including my childhood friend’s brother K-. But his pain, his raw nerves, I didn’t have to look anywhere for that. I was built out of that stuff.

Omar Little was described as a guy from Baltimore who robs drug dealers, though he doesn’t sell or use. He’s gay, doesn’t hide it, and operates as something of the Robin Hood of his community. To play Omar, I tapped into the confidence and fearlessness of people I’d known growing up. I’d held guns before, but never in preparation to use one, and I didn’t want to be one of those dudes holding their gun all sideways. Concerned about my tiny wrists I asked K– to show me the proper way to hold one.

I practised at it, over and over. Omar had to look like a guy who knew how to use a gun. Without that detail looking real, nothing else would have flown. You can have the whole neighbourhood yelling: “Omar coming!” and running for cover, but if I walked out there holding that shotgun like I didn’t know what I was doing, I’d get laughed off the screen.

As for Omar’s homosexuality, it was groundbreaking 20 years ago, and I admit that at first I was scared to play a gay character. I remember helping my mother carry groceries to her apartment and telling her about this new role that I booked. I knew from the jump he was going to be a big deal. “This character is going to change my career,” I said. “But the thing is … ” I hesitated. “He’s openly gay.”

“Well, baby,” she said, “that’s the life you chose and I support it.” She hadn’t embraced the arts or my interest in them, but to me, that was her version of encouragement. I think my initial fear of Omar’s sexuality came from my upbringing, the community that raised me, and the stubborn stereotypes of gay characters. I made Omar my own. He wasn’t written as a type, and I wouldn’t play him as one.

A new, more potent fear dug its way into my mind: this dude is a straight-up killer. He strikes fear into the heart of anyone in his path. But everyone knew I wasn’t that guy. I was 35 years old when I started on The Wire but carried that scared childhood self close; he lingered under my skin, just below the surface. So the self-talk got fierce: there is no way you can pull this off. You have nothing to pull on. There’s nothing remotely you have in common with this guy.

The change came when I stopped trying to bring myself to Omar and started doing the opposite. I dug into how he was like me, tapping into what we had in common. Omar is sensitive and vulnerable and he loves with his heart on his sleeve. You can say what you want to him – it rolls right off – but don’t you dare mess with his people. He loves absolutely, fearlessly, with his whole entire being.

After clicking with that, I understood him completely. I came up with the narrative that his vulnerability is what makes him most volatile. When he cries and screams over his lover’s tortured and murdered body, screaming in the halls of the morgue and hitting himself in the head, that looks real because it felt real to me. When Omar goes after Stringer Bell and everyone else responsible, he is driven by love and loyalty.

I also loved how Omar is the opposite of the stereotypical hood types. He isn’t about the cars, clothes and women. He doesn’t fit into any of the boxes people might try to stuff him in, whether that’s morally or sexually or something else. In so many ways, he stands alone. But he also feels pain, especially when his loved ones – Brandon and then, later, Butchie – are killed in these horrific ways. Both times the pain cuts even deeper since they are killed because of him, to send a message to him, because his enemies can’t get to him. That’s a particular kind of hurt.

That’s the flip side of getting into a character; you wake up that sleeping beast, those actual memories, those real emotions. I meditate on painful things all day long for a scene and when it’s over, it’s little wonder I’m tempted to go off and smoke crack. Drugs had long been a smokescreen, a cocoon, a means for me to hide from the real. In character, sometimes things get too real for me. I don’t “disappear” into a character; I go through him and come back out. But when I come back out, I’m not the same.

As the years went on, I got out of my own head and came around to see that The Wire was bigger than Omar, bigger than Mike Williams, bigger than Baltimore or even just the Black community. David Simon knew what he was doing. The show, which added to its world each season, was creating a portrait of America.

I remember the day toward the end of season three when we shot the scene where Omar kills Stringer Bell. It ate at me, and I avoided Idris Elba, who played Stringer, all day. I was troubled by it, the message. Why is this the way two Black men settle their differences? It bothered me, especially since Stringer was making his way through college, setting up in real estate, trying to get out of the game. And I had to kill him.

I talked to the writers about it, about why that had to happen. Dramatically, for story purposes, I understood. But as a Black man who felt he was representing his community, it bothered me. There was a larger problem than maybe I could articulate at the time. But it stayed with me.

The Wire was real in the sense that those characters whose lives were in the street could be killed off at any time. That’s how it really is. Guys like Stringer Bell get killed. Guys like Omar Little get killed. The realism of that world demanded that Omar too meet his fate. So when the time came for him to go, I’d had enough preparation. But it was not easy.

Omar is killed unexpectedly, buying a pack of cigarettes, by a young kid in the streets. It’s not played for dramatic effect – there’s no slo-mo, no music. It’s even early in the episode; it’s just something that happens, just as it would really happen. (Even his body tag is mixed up at the morgue.) The actor who played the shooter, Thuliso Dingwall, was 10 or 11 at the time. We rehearsed it, but during the run-through we didn’t set off the squib, that small stick of dynamite on my clothes. The first time he saw the effect go off was when we were rolling; that scared look on his face you see on screen is the real human being, the real little boy going into shock. He drops the gun and is freaked out; that’s not acting. We all stepped right into the real there.

After they yelled cut, he started crying, bugging out. “Is he all right? Is he all right? Michael?!” I had to console him. We had to wait a while to make sure he was OK to finish the scene. Other setups were needed, and I had to lie there in that pool of blood. I’d died on screen before – and I would again – but lying there, as Omar, was different. It felt like the end of something.

During a break that day, I went to the trailer and one of the wardrobe people, Donna, came in to change my shirt. She saw me sitting in front of my vanity mirror, headphones on, spacing out, listening to Tupac’s Unconditional Love. I was going into a dark place and she could see it all over my face. “Unh-uh, no,” she said, “we’re not doing this today, Michael. We are not doing this today. Snap out of it.”

I met her eyes and came back, but I couldn’t avoid it for ever. It was strange energy on the set that day. People were trying to avoid having any feelings about the show coming to an end. People had come to like me and adore Omar, and there was this resistance, like no one wanted to allow themselves to feel.

Omar’s death was also the death of something that had grown inside of me, something I’d grown inside of, merged into. That was a crippling realisation. I remember thinking that if I wasn’t Omar any more, then who was I? I had defined my worth through this fictional character, and now I was just Mike again. I felt stripped, lost, emptied out. It was like this darkness crept in on me during the end of that show.

As the final episodes of The Wire aired in 2008, a young senator, Barack Obama, was running for president. In an interview, he said Omar Little was his favourite character. The comment was picked up: clearly, Obama knew all about Michael K Williams. But deep in the grip of addiction, Williams had not heard of the “Harvard-educated dude with the African name and dark skin who might become president”. Soon, though, their paths would cross …

In March I was invited to a town hall Obama was doing at the Forum in Harrisburg, near my mom’s house. I’d just come off a three-day cocaine bender and was whacked out of my mind. Shooting a movie in Rhode Island, I threw on a sport coat and jumped on the Amtrak and went down to Philadelphia. I got to this packed auditorium and one of the female campaign volunteers found me, pinned a Hope button on me, and took me by the arm.

I was in the back searching for my family when a campaign worker got on the stage and announced over the loudspeaker: “Michael Kenneth Williams has just endorsed Senator Obama for president of the United States!” The room went crazy and the next thing I knew all this Secret Service had circled around me and I was like: what is happening? It was surreal.

After Obama’s speech, his campaign staff invited me and my family to come downstairs to meet him. After we all got cleared, we went through and waited for him to walk in. I was intimidated, meeting the future president of the United States. He was not just the frontrunner at the time but a global celebrity, and it was wall-to-wall people down there. He came down the steps and my cousin’s wife greeted him. “Senator Obama, I understand that you watch The Wire and you’re a fan of Michael K Williams and he’s here to … ”

“Where Omar at?” Obama yelled out. “That’s my man! The man with the code! Where’s he at?” He found me in the sea of the crowd and grabbed me, gave me the homeboy handshake into a hug and pulled me in. “What’s good with you, man?” he asked.

“G-G-God bless you, bro,” I managed to stutter out. I couldn’t even put my words together I was such a mess. Obama shook my hand, and I could see it in his eyes. He was like, I don’t got time for this. He kept it moving. I was not in my right mind. I told people I was nervous, but I actually had lockjaw from too much cocaine.

I wasn’t yet in the headspace to even make sense of meeting Obama, much less make use of it. I would meet him again a few years later – when I was more ready to embrace the kind of influence he had, and accept the kind of influence I could have. But not that day. I was nowhere near ready yet.

In the summer of 2016, my documentary series Black Market and HBO’s The Night Of started airing within about a week of each other. Both shows explored issues of class, marginalised communities, criminal justice and underground economies. I was doing press for both simultaneously, so a lot of the questions were on these topics and I wanted to be able to answer. By this point I had hooked up with the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] to be its ambassador for smart justice, but it was mostly a campaign where they used my face. I didn’t know yet what I needed to know, and it felt like time to grow up.

“Will you help me figure this out?” I asked Michael Skolnik, a film producer turned activist whom I met through Boardwalk Empire. “I got people going back in my family, friends, my nephew Dominic has been locked up for 18 years. Jimmy’s got nine life sentences. This shit is personal to me, and I gotta do it right.” Michael agreed and we started to meet every week or so to talk about things I could do. I didn’t want to be just a face. I wanted to get my hands dirty. Or, depending how you look at it, clean.

The capper was a meeting in September 2016 at the Obama White House among some heavy hitters: former attorneys general, major CEOs, religious and civil rights leaders, and other big-name activists. Obama was in his last year – the home stretch – and his administration had been doing important work in criminal justice reform.

There’s nothing like getting invited to the White House to make you feel like an impostor. Once the excitement wore off, that familiar voice kicked in: who do you think you are? I thought of all the things I didn’t know. I thought about my mother, who complimented me about first being on Obama’s radar. But the end of that conversation? The last thing she said? “You know, when you’re in these rooms, son, just smile and nod your head. Don’t try to talk.”

Just getting invited to meet the president means you must’ve done something to earn it, but I didn’t feel that.

“Yeah, but I’m just an actor,” I said to Michael. “Why do they want me to be there?”

“C’mon, Mike,” he said, “this isn’t just about being on TV. This is your personal life.”

“Yeah, but, I don’t … What do I know about this?”

“A lot,” he said. “More than most people. You’ve lived it.”

The White House meeting was about 25 people in the Roosevelt Room, a windowless space with a fireplace, oil paintings and that grand wood table; I felt like I’d stepped into a history book. Michael must’ve sensed my nerves because he came over to me while we were waiting. “Relax, Mike,” he said. “Remember what they say: those closest to the problem are closest to the solution.”

Oh shit, I thought. The lightbulb went on in my head. Maybe I do know something.

Besides, I couldn’t have hidden if I’d wanted to. They put me right in the middle of the table, across from an empty chair and I knew who was going to sit there. Obama came out of the Oval Office into the room and began taking ideas from everybody. He mostly listened and Valerie Jarrett took notes.

When it was my turn, I spoke on what I knew. “This is very personal to me,” I said to the room, trying to squash the nerves, feeling all those eyes on me. “My nephew Dominic has been in prison for 18 years, for a crime he committed as a teenager. He’s mentoring men twice his age, and I want to honour him whenever I speak on this. Growing up, I saw family members, friends, locked up, killed, and have seen how this affects communities like mine, poor communities of colour.”

Later on, I thanked Obama for all the clemency work he was doing and asked him what he planned on doing for the female population that was incarcerated, because up till then it had mostly been men. It was really the first time I realised I had agency, a voice, a life experience that mattered. That’s what I could bring to the table. I could use my visibility not to score drugs or get a table at a restaurant or even make myself feel better but to actually contribute. Do something.