Most boxers will tell you the punches don’t hurt as much as the blows they take outside the ring.

Frequently being forced to take fights at the last minute, rarely being paid what you were promised and then finding your manager was working for the opponent. Those are the kind of setbacks that might fuel the anger, rage and bitterness known by many in the sport.

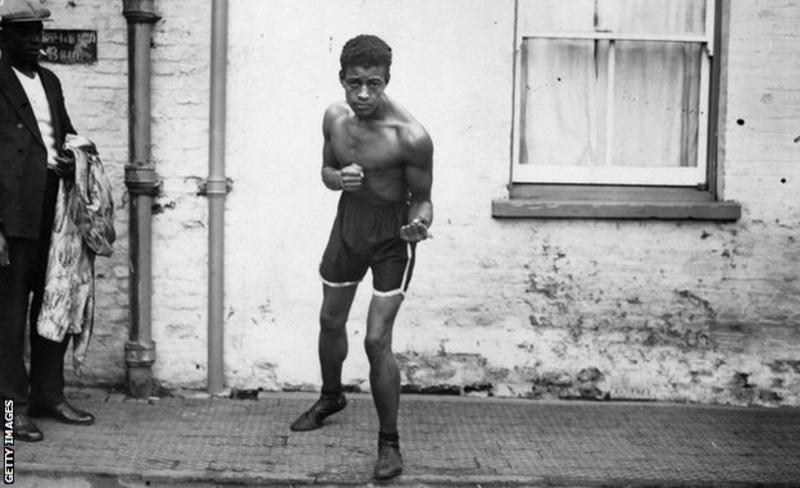

So, imagine being Len Johnson, a retired middleweight boxer with more than 100 fights behind him, entering Manchester’s Old Abbey Taphouse pub after a tough day driving buses around town on a September night in 1953.

Len Johnson, then in his early 50s, was teetotal but he was ordering a round for his friends. Whatever optimism, banter and conversation the group had brought to the establishment was swiftly brought to a close in one moment. He was refused service and thrown out because of the colour of his skin.

It wasn’t the first time the boxer had been discriminated against for being black. But Johnson fought back, just as he had done his whole career.

The eldest of four siblings, Len Johnson was born on 22 October 1902 in Clayton, Manchester to a father from Sierra Leone and a mother from Ireland.

His introduction to boxing came after he got into a fight at work and his dad, Billy, took him to watch a local bout. Johnson didn’t immediately take to the sport, and it was to his surprise that his father signed him up to fight a couple of weeks later.

He had little knowledge of how to box, let alone how to prepare, but he trained as best he could. His mother provided an old clothes line which he skipped with.

The contest took place in 1921, at the Alhambra Theatre in Openshaw, Manchester. His opponent was fellow local teenager Jerry Hogan.

The inexperienced Johnson came out on top, with a third-round knockout, but it turned out there was a bit of luck involved.

“Jerry shoved his chin on to my hand and down he went for the count. I really had no idea how I knocked him out!” Johnson is quoted as saying in Boxing’s Uncrowned Champion, Rob Howard’s book about him.

That first unlikely victory – lucky or not – was just the beginning.

Len Johnson’s father had been a boxer – and both gained experience from fighting in ‘booths’ at travelling fairs, accepting challenges from the public. These ’bouts’ would not last long, but at the time were a considered a useful way to hone your craft.

This was how Len Johnson acquired the defensive skills that would become his trademark. Over time, he developed into a fundamentally sound boxer who managed to avoid a lot of blows and countered well enough to end 36 of his 93 wins by knockout.

In the ring, after a faltering start that almost prompted retirement, he became an opponent that people were happy to avoid. His breakthrough came in 1925 when he defeated the reigning British middleweight champion Roland Todd twice in seven months.

That same year, he also beat Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis, a boxer who Mike Tyson once described as “probably the greatest fighter to come out of Britain”.

These victories should have been the springboard for a sustained period of domination and success, for Johnson.

But they weren’t. They were non-title bouts, and there was only one reason why.

The British Boxing Board of Control’s ‘rule 24’ stated that both contestants for one of their titles needed to have been “born of white parents”.

The rule, given government backing when introduced in 1911, remained in effect until 1948. That same year, Dick Turpin became Britain’s first black boxing champion, beating Vince Hawkins on points in front of 40,000 people at Villa Park. Turpin’s brother Randolph would in 1951 become world middleweight champion, defeating Sugar Ray Robinson.

Johnson wasn’t the only successful fighter who found himself locked out of the sport’s elite during that time. About 30 miles up the road in Liverpool there was a Guyanese boxer named Ritchie ‘Kid’ Tanner who was considered as good a featherweight as any, but never fought for the biggest prize.

The lack of acceptance for black boxers wasn’t only a British issue either. At the start of the 1900s, the United States had responded with anger at the notion that the best heavyweight was a black man.

Jack Johnson – no relation to Len – endured such hostility during the seven years he carried the title of world champion from 1908 that he was eventually forced to flee his country because of a racially motivated conviction. He was pardoned in 2018, 72 years after his death.

Len Johnson was also forced into an escape. In 1926 he left Britain and spent six months in Australia, beating Harry Collins to win the Empire middleweight title (it would now be considered the Commonwealth title).

Johnson said the experience did him “the power of good”, although a triumphant return to Britain did not follow. He was informed his title win wasn’t recognised in his homeland. It was one of the many factors that led to his disillusionment with the boxing world.

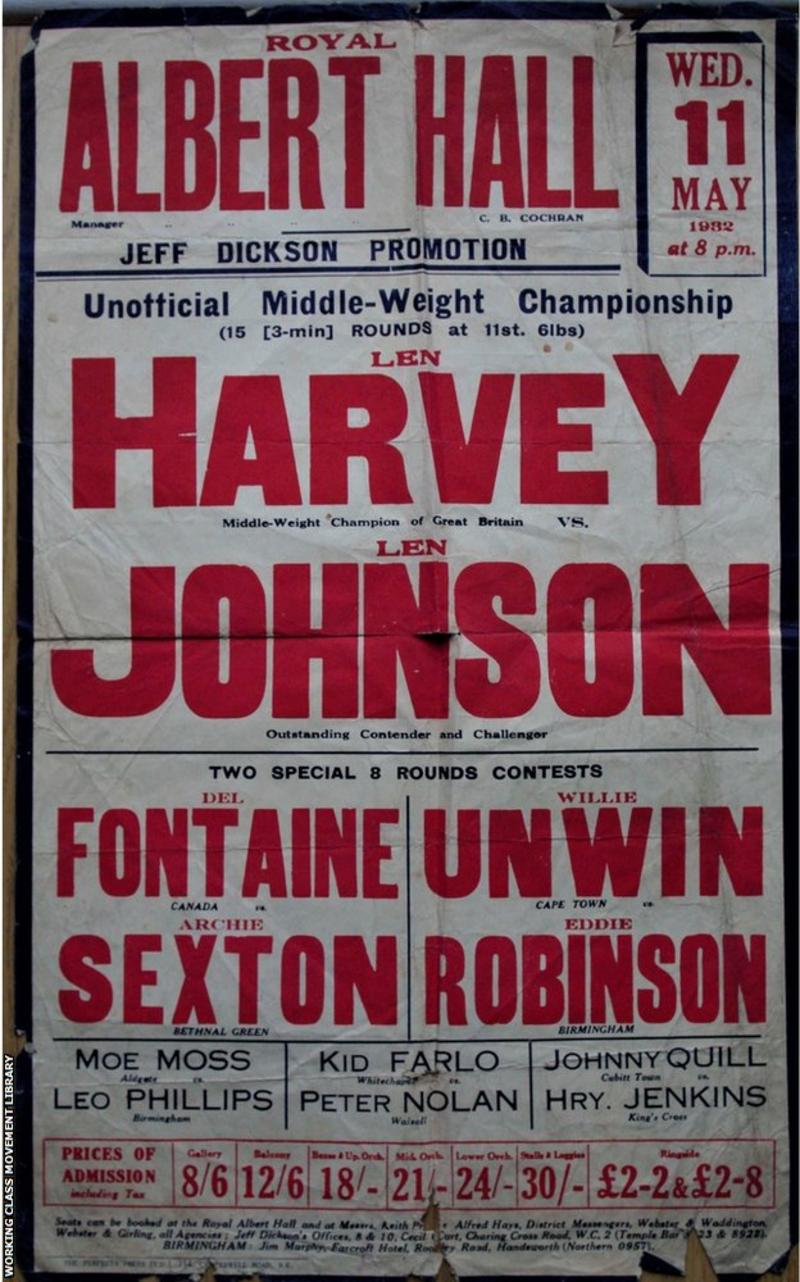

“I’m barred from the Albert Hall and the national sporting club. In fact, whenever there is big money I’m kept out of it,” Johnson said in 1930, as quoted in Michael Herbert’s book about him, Never Counted Out.

“The prejudice against colour has prevented me from getting a championship fight. I feel now that there is no use whatever going on with the business.”

Johnson’s professional career was drawing to a close. His final fight came in 1933.

His affinity with the sport continued until the outbreak of World War Two, and he would still occasionally fight in the booths at travelling fairs.

But now the second act of his life was starting. One with a political punch.

Towards the end of the war, Johnson had joined the Communist Party. He was active in the community in Moss Side, Manchester, and frequently intervened in cases involving racial discrimination.

He had also been one of the local representatives at the influential Pan-African Congress of 1945, hosted in his home city.

During his boxing career, Johnson was very much considered a “local hero” in his community, as author Herbert explains.

“They’d all stay up when he had his big fights at Belle Vue,” he says. “They’d wait until his taxi brought him home and there’d be a big cheer.

“The people of Manchester did respond to him – and he was able to get prominent people in the city, the Lord Mayor, to sign petitions or support campaigns.”

After retiring from boxing, Johnson had also become close with Paul Robeson, the American NFL player, singer, actor and political activist. Robeson encouraged Johnson in his activism and desire to end the racial discrimination he had suffered, inside and outside the ring.

One of Johnson’s great successes came amid the fallout from him being banned by the aforementioned Old Abbey Taphouse, just south of Manchester city centre, in 1953.

“Len and best friend Wilf [Charles], went away to the mayor, got in all the press and brought around 200 people down [to the pub] with them,” Rachele Evaroa, co-director of The Old Abbey Taphouse, explains.

“As a result, the landlady served Len, even though he didn’t drink, which meant the colour bar got overturned in loads of other pubs in Manchester. It was a real landmark moment.”

Johnson was never able to turn that success into a sustained run in the political sphere, however. Despite his persistence, he ultimately failed in his pursuit of a position on Manchester City Council.

Johnson died in 1974, aged 71. His struggles and successes might speak of a different time, but there is also a great relevance with the present day.

The Old Abbey Taphouse is now a community pub, where the legend of Johnson and Wilf is celebrated. This October, during Black History Month, it is hosting a conference where members of Johnson’s family are expected to attend as well as historians and actors who appeared in Fighter, a play about his life.

There is also a campaign for a monument be built in his honour, in the city he helped change.

Supporters speak of the recent success behind a similar movement in Plymouth, where crowd funding raised £100,000 to erect a statue of Jack Leslie, the footballer who in 1925 was dropped from the England team when selectors discovered he was black.

Deej Malik-Johnson, the co-founder of Black Lives Matter Manchester, has led the push by spreading the word about Johnson and managing an online petition.

“He was always there supporting people,” Malik-Johnson says. “Like so many, he was doing what was right but not getting the rewards for it. For him to finally get that recognition would be huge.”

Manchester actor and fellow campaigner Lamin Touray is a member of Moss Side Fire Station Boxing Club, where it is believed Johnson briefly worked.

“He’s relatively unknown in Manchester and relatively unknown in the UK,” Touray says. “He should be a national treasure.

“He’s had nearly 130 fights, winning 93. He is essentially the British Muhammad Ali – so the fact that we don’t know who he is, it’s shocking.

“He was a fighter in and out of the ring and I think that’s what’s really important to remember.”

Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham feels Johnson’s story “absolutely needs to be told and celebrated”, while the leader of Manchester City Council, Sir Richard Leese, is also open to the idea of a monument in the city.

“I think it would be great to have a statue of Len Johnson in Manchester,” says Sir Richard.

“My colleague Luthfur Rahman, who is our executive member for statues, is doing a review and look at what we’ve got and what we haven’t got so that we do have public representations that really do represent the whole history of the city.”

The boxing booths taught Johnson to take on all comers, whoever the opponent, and that filtered through into all areas of his life.

Although denied his place as a champion in sport, no one can deny his legacy, which continues to inspire today. Maybe that’s no surprise for a man who was ahead of his time.