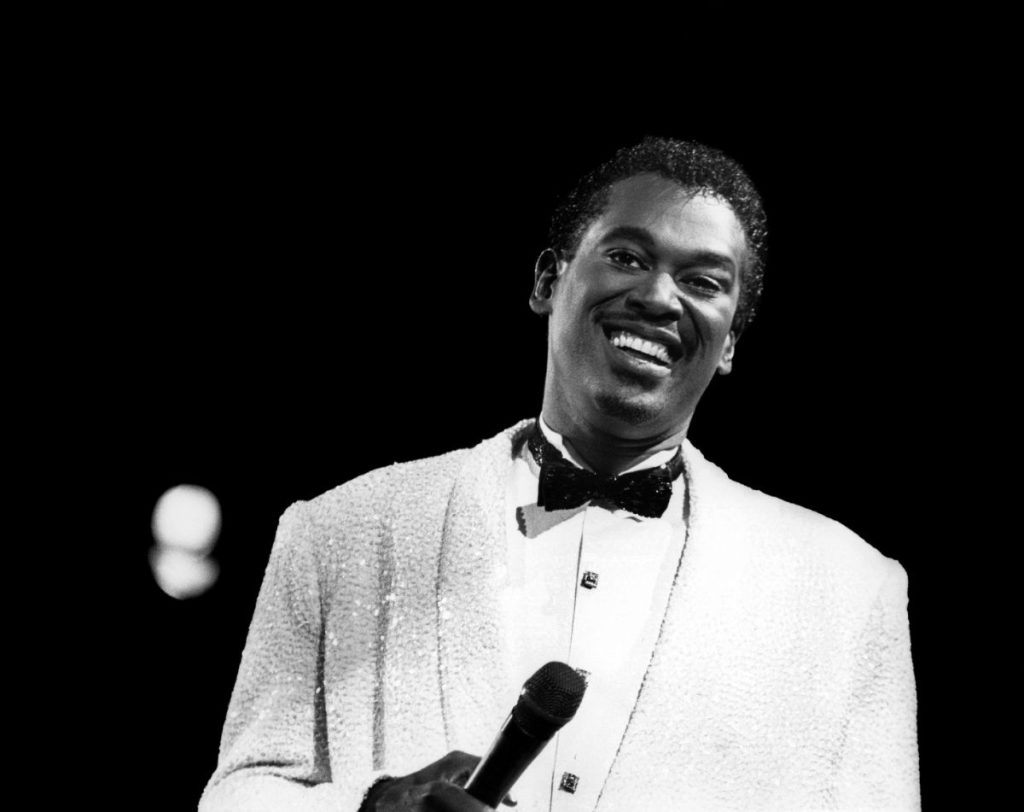

A new documentary looks back on the career of a singer whose undeniable talent wasn’t always enough for a limited and image-obsessed industry

Luther Vandross is R&B music’s tragic hero – a soulful soloist who was most popular while singing backup for rockers, a strict disciplinarian who could control everything except his weight, a hopeless romantic who died alone, miserable and far too young.

It’s a sad story revisited in Luther: Never Too Much, a new documentary currently in limited theatrical release that is expected to begin streaming early next year. Directed by the biographical film-maker Dawn Porter, produced by Jamie Foxx and arranged by Robert Glasper, the 160-minute film is a stark reminder of the aversions and prejudices that stalled Vandross’s breakthrough and ultimately broke him.

Stardom should have happened so much earlier for Vandross, who really did have it all: songwriting chops, producing knack and a velveteen vocal clarity and dexterity to rival Whitney Houston. But record execs refused to see past his dark skin and overweight physique. The stigma had Vandross at once determined to succeed and self-conscious about stepping into the spotlight.

A native New Yorker, Vandross convinced his friends to form a group – but relegated himself to a background role. Still, there was no missing him when the group appeared on the first season of Sesame Street, where Vandross helped set the groovy template for children’s songs. Despite continual rejection from record labels, Vandross dropped out of college to pursue his music dream. On a lark, he wound up in the studio session for Young Americans and was vibing to the project so hard that David Bowie hired him to sing backup and arrange the vocals.

Vandross’s work on the refrain for the titular song alone should have had industry bigwigs reconsidering him as a leading man. Instead, it typecast him as a premier background singer and led to more lucrative work in advertising. His first jingle, for Gino’s Pizza, is where Vandross conceived of a ghostly vibrato that had the control room erupting with excitement. “This is gonna end up being his thing,” Deborah McDuffie, the producer on the commercial, recalls in the doc. “We were thinking [about] it in the control room, but he was thinking [about] it on mic. ‘Oh I’m not doing this in any more jingles’ – and he never did.”

Record execs weren’t just hung up on Vandross’s looks. To their ear, his sound was out of tune with R&B; at the time he was attempting to go solo in the late 70s, the genre was dominated by Gamble and Huff – the Philadelphia music factory behind the O’Jays, Lou Rawls and other unapologetically macho acts. It took Roberta Flack firing Vandross from her tour out of a desire to see him fulfill his destiny as a solo artist for him to finally go his own way.

He invested a chunk of his earnings and called in favors from Whitney’s mother, Cissy Houston, the Grammy-winning composer Marcus Miller and other super-talented friends to cut the demo for Never Too Much – the buttery groove that effectively changed the tone of R&B music going forward. In the doc, Miller, who plays bass on the record, remembers reading the sheet music for the first time and thinking, “this is a quirky little bassline”. It made the song recognizable from the first note.

But even as the hits kept coming, Vandross was pigeonholed as R&B – or “African-American”, as Clive Davis says flatly in the doc. The coded language, explains the acclaimed music journalist Danyel Smith, was typical of an industry that saw music as a racially bespoke commodity and packaged it that way. Epic Records, Vandross’s label, marketed him exclusively to Black audiences; it hardly mattered that suburban white women were crazy about him, too.

Vandross maintained his dreamboat status through wild fluctuations in weight, a public struggle that became comic fodder everywhere from Eddie Murphy Delirious to Spike Lee’s Kings of Comedy. When people weren’t snickering over Vandross’s weight, they were speculating about whether he was gay – a lifestyle that would have clashed with his carefully crafted romantic persona.

Porter does an admirable job of wrestling with this in the doc; she fits footage of Vandross and defenders arguing for his right to privacy around a bombshell clip of Patti LaBelle – a famous Vandross friendship that started with him launching her official fan club in high school – outing Vandross 12 years after his death. “I loved, loved, loved that song Any Love before I worked for Luther,” says Max Szadek, Vandross’s personal assistant. “But once I started working for Luther, I could see that the desperation described in that song was real. And I hated that song after that because it always reminded me that he wasn’t seeking love. He was seeking any love.”

Vandross sought it most openly from the music industry. He was nominated for a Grammy nine times before winning one for Here and Now in 1991. When rap music stormed the pop charts at the turn of the century and a new generation of Black male R&B singers adopted tougher guises in response, it seemed as if Vandross’s lifelong dream of winning a Grammy and topping the US pop charts would never happen. Then in 2003, after leaving Epic for Davis’s J Records, Vandross scored his first official mainstream hit with Dance with My Father – but there was no wallowing in the success. Not long after the song’s release, Vandross suffered a stroke that scorched his singing voice and briefly confined him to a wheelchair. Two years later, in 2005, he died at age 54.

Decades on, Vandross endures as a timeless crooner whose vulnerability and sincerity set the standard for male R&B vocalists, practically an endangered species now. In the documentary, Vandross gets due credit for his role in breaking the color barrier in the music industry – where, ultimately, he made truer classifications for himself: adult contemporary, quiet storm. As much as it hurts to see Vandross cross over so late, the film softens the blow by proving why the public affection for him has only compounded since. “If we were able to talk to Luther at the time as fans,” says Foxx, reconsidering the Vandross punchlines, “we would’ve said, ‘Whatever weight you are. We don’t care. We just love you.’”