A wealthy businessman with a reputation for being frugal, Peter Obi has emerged as a powerful force ahead of February’s Nigeria’s presidential election, energising voters with messages of prudence and accountability that are amplified by an army of social media users.

In a country that seems to always be on the lookout for a messiah to solve its myriad problems, young social media-savvy supporters have elevated Mr Obi to sainthood and are backing his largely unknown Labour Party against two septuagenarian political heavyweights.

The way he has attracted supporters seems to border on populism – a tag he and his supporters would denounce, but some of his rhetoric might be encouraging that.

“It’s time to take your country back,” he often says.

“[This election] is the old against the new,” he told the BBC.

His name is often trending on social media on the back of numerous conversations sparked by his supporters, instantly recognisable from their display picture of his image or the white, red and green logo of his party.

These are mostly urban under-30s who refer to themselves as the “Coconut-head generation”, because they are strong-willed, independent-minded and contemptuous of older politicians who, they say, have done little for them.

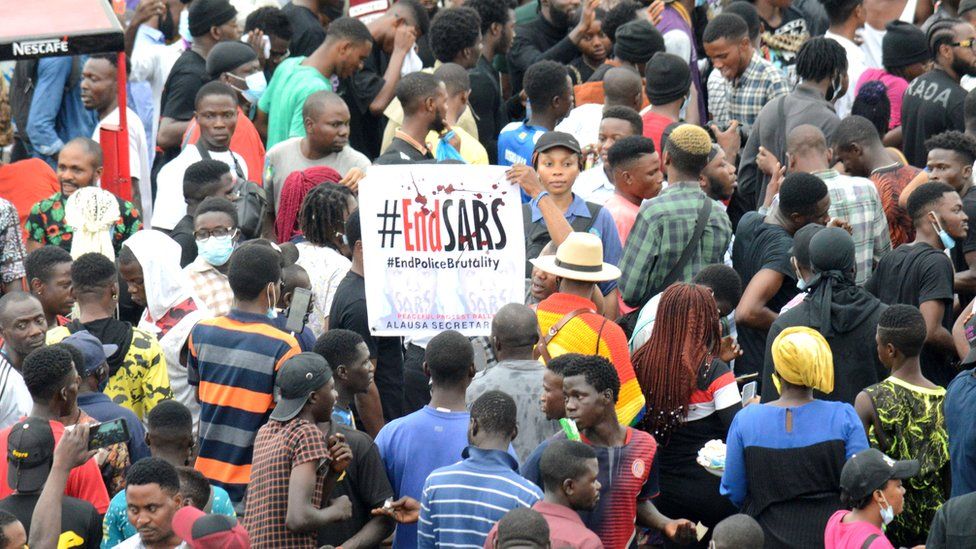

Many of them, like Dayo Ekundayo from the eastern city of Owerri, were involved in the EndSars protests that forced the disbandment of a notorious police department two years ago and also morphed into calls for better government.

Now, they are deploying the same strategies that mobilised hundreds of thousands of young Nigerians and raised millions of naira within weeks for the 61-year-old who they consider an alternative to the two parties that have dominated politics since the end of military rule in 1999.

“Which Nigerian politician has ever held office and has his integrity intact? I do not see any other logical option for young people in Nigeria,” said Mr Ekundayo.

He has already been involved in a march for Mr Obi, and is providing logistics and mobilising students for the campaign as he did during the EndSars protests.

But opponents say Mr Obi is a political impostor, one of many who spring up at election time with delusions of being a third force that will wrestle power from the traditional parties.

Many supporters of the main opposition Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and neutral observers agree he is head and shoulders above the other candidates, but say he lacks the nationwide popularity to win the election and have warned his supporters that they risk wasting their votes.

They believe he is a distraction from the common goal of removing the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) from office, and could split the opposition vote.

A devout Catholic from eastern Nigeria, they point to his lack of popularity in the Muslim-dominated north, whose votes are considered critical in winning presidential elections.

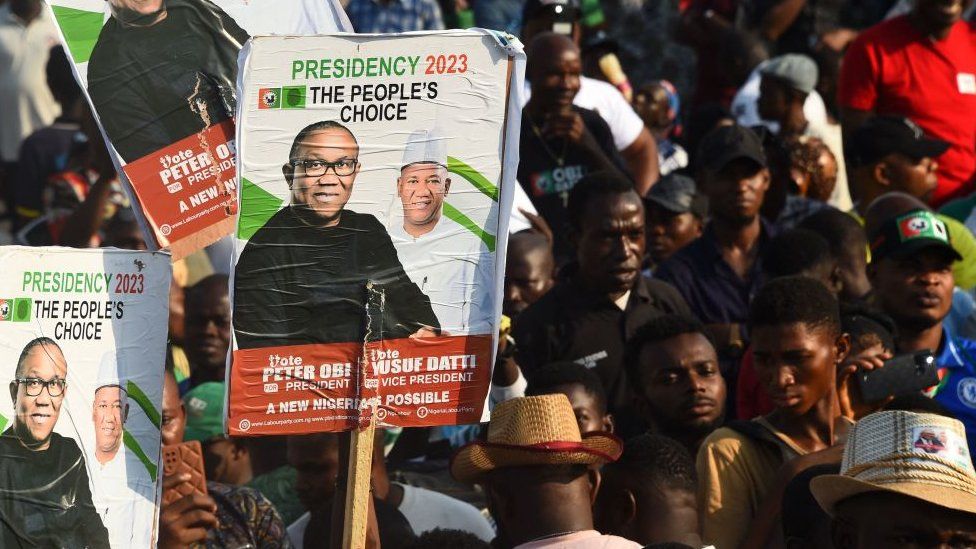

But Mr. Obi and his running-mate Yusuf Datti Baba-Ahmed have had strong showings at party rallies in the north, attracting large crowds in states where the popularity of the Labour Party was doubted – although such crowds can be hired by politicians.

His critics also question whether he truly represents a break from the corruption he routinely lambasts, pointing out that his name popped up in the leaked Pandora Papers which exposed the hidden wealth of the rich and powerful in 2021.

While he was not accused of stealing money, he failed to declare offshore accounts and assets held by family members, citing ignorance.

He was also accused of investing state funds, as governor, into a company he had dealings with. He denied any wrongdoing and points out that the value of the investment has since grown.

Mr Obi repeatedly says he is not desperate to be president, which is ironic for a man who has changed parties four times since 2002.

He dumped the PDP just days before its presidential primary in May and the party went on to choose the 75-year-old former Vice-President Atiku Abubakar as its presidential flagbearer.

Critics say he pulled out of the contest because he knew his chances of winning were slim but he cited wrangling within the PDP, where he was a vice-presidential candidate in 2019, for deciding to cross over to the Labour Party.

His supporters are also convinced that he was pushed out of the PDP because he refused to bribe delegates at the party primary and have coined the phrase: “We don’t give shishi (money)” as a buzzword for his famed frugality and his prudence in managing government funds in a country with a history of wasteful expenditure by public officers.

They regard him as an unconventional politician prepared to take on the APC and PDP behemoths seen as different sides of the same coin, who they accuse of dipping their fingers into the public purse.

There is also a religious and ethnic twist to his candidacy.

In a country where roughly half the population is Christian, his supporters hope that this will bolster his chances of winning, as after eight years of President Muhammadu Buhari they would not want another Muslim – the APC’s Bola Tinubu, 70, or the PDP’s Mr Abubakar – to take office.

And while he has downplayed his religion, Mr Obi has become a constant face at the large auditoriums of Nigeria’s Pentecostal churches, to rapturous receptions, and he has also singled out Christian communities in the north for visits.

This has drawn criticism from opponents who accuse him of bigotry and trying to create divisions through religion, accusations he has denied.

Some also support Mr Obi because of his ethnic background. Igbos make up the country’s third largest ethnic group, but Nigeria has had only one Igbo president, largely ceremonial, since it freed itself from British colonial rule in 1960.

Many Igbos accuse successive Nigerian governments of marginalising them and hope that Mr Obi will rise to power so that the south-east, where most of them live, would see greater development and so counter the pull of secession groups like the Indigenous People of Biafra (Ipob).

Critics say he is a supporter of Ipob, a group designated as a terror organisation by Nigeria, but he told the BBC that he is a firm believer in Nigeria and that his position on the different “agitations across the country” is to dialogue and reach a consensus.

He said Nigeria’s number one priority is the issue of insecurity because it has become an existential one “that must be dealt head-one decisively”.

“If you deal with it [security] today, you deal with inflation because farmers would go back to farms and that would reduce food inflation,” he said.

A philosophy graduate, he worked in his family’s retail businesses before going on to make his own money, importing everything from salad cream to beauty products, and baked beans to champagne, while also owning a brewery and holding major shares in three commercial banks.

You can normally recognise a Nigerian billionaire from a mile off but Mr Obi is thrifty and wears it as a mark of pride.

He is quick to point out that he owns just two pairs of black shoes from midmarket British chain Marks and Spencer, prefers a $200 suit from Stein Mart to a $4,000 Tom Ford suit, and always insists on carrying his own luggage, rather than paying someone else to do it for him.

Even his children are not spared his frugality. His 30-year-old son was denied a car, he said, while his other child is a happy primary school teacher – a rarity in a country where a politician’s name often opens doors to more lucrative jobs.

The OBIdients

Despite the financial controversy, his tenure as governor of Anambra state has become a reference point for his presidential campaign.

His supporters point out that he invested heavily in education and paid salaries on time – the simple things that most Nigerian state governors tend to neglect.

He also left huge savings in state coffers at the end of his two four-year tenures, another rarity.

But Frances Ogbonnaya, a university student in Anambra state when Mr Obi was governor, is surprised by the praises being sung in his name, describing his tenure as unremarkable.

“Who saves money in the face of hunger? Who saves money in the face of a lack of facilities?” she asked rhetorically.

But it is his reputation for frugality and sound management that has attracted a horde of supporters, known as OBIdients.

Some have been accused of cyberbullying and labelling anyone who does not vote for him in next year’s election an enemy of the state.

He responded with a tweet calling on his supporters to “imbibe the spirit of sportsmanship”, but it has done little to calm them down.

They are quick to remind anyone who tells them that elections aren’t won on Twitter, that data from the electoral body shows a jump in new registered voters, most of them young people.

But this is not the same as actually turning out to vote on election day.

With weeks to the election, there is no denying the momentum behind Mr Obi but cynics also point to the lack of a nationwide party structure to support the view that, while possible, an Obi presidency remains highly improbable.

“The structure that has kept us where we are, the structure that has produced the highest number of people in poverty in any country, the structure that has produced the highest number of out of school children, that is the structure we want to remove,” he said.

He retorted that his structure is “the 100 million Nigerians that live in poverty [and] the 35 million Nigerians who don’t know where their next meal will come from”.

If half of those turn out to vote him on election day, it might very well be all that he needs.