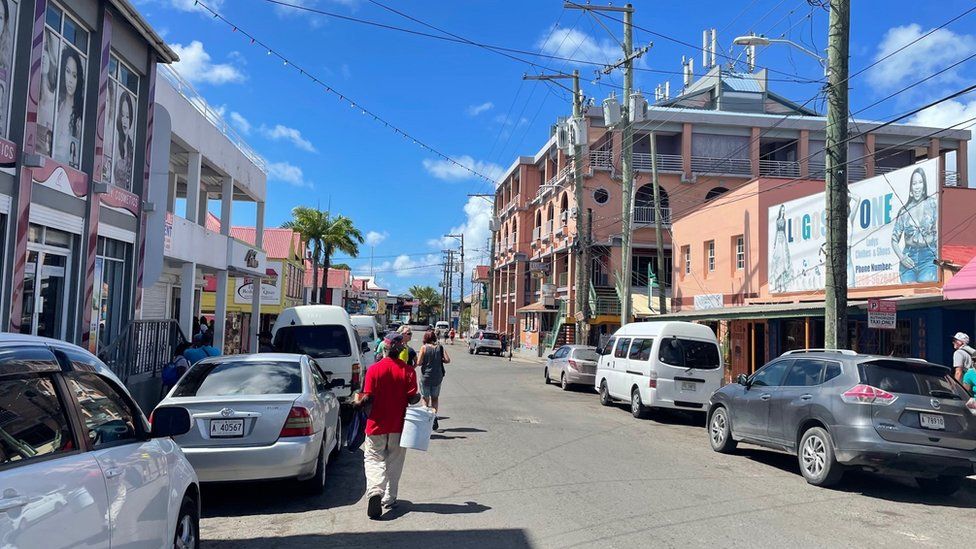

How did more than 600 Cameroonians come to find themselves stranded on a Caribbean island that many of them had never heard of? Journalist Gemma Handy reports from St John’s in Antigua.

Daniel fights to hold back the tears as he recounts the day his two younger brothers were shot dead by militia during a trip to the market in his native Cameroon.

They are among more than 6,000 people to have been killed amid a bitter secessionist war that has been raging for six years in the Central African country.

Hundreds of thousands more have been forced from their homes since violence broke out in 2017 between security forces and Anglophone separatists who say they face discrimination in the majority French-speaking nation.

Daniel’s despair intensifies as he explains how he faces life imprisonment or death should he return – and pleads with the authorities not to send him home.

He was hoping to reach the United States, which last June offered temporary protected status to Cameroonians already in the country, and where he had planned to flee under the radar.

And neither is Daniel, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, alone.

He is one of more than 600 desperate Cameroonian migrants to have instead found himself stranded on a tiny island of 94,000 people in the Eastern Caribbean via what appears to have been an unscrupulous people-smuggling operation.

Some forked out as much as $6,000 (£5,000) on charter flights marketed on social media by bogus tour companies pledging to organise immigration logistics as part of the package.

Most of those who have unwittingly ended up in Antigua – an island some of them said they had never heard of before – say they had only expected to stay for a few days before being taken to South America, from where they had planned to make their way north to the US.

But when the transport failed to materialise, they were stuck in Antigua with no money left to fund their onward journey.

The fiasco erupted in the wake of attempts by the government of Antigua and Barbuda to establish a direct air route between the twin isle nation and Central Africa.

Three centuries after Antiguans’ ancestors were first forced onto slave ships from Africa to work on brutal British-owned sugar plantations on the island, many welcomed new linkages with the motherland. The first charter flight touched down – fittingly – on Independence Day on 1 November with a water cannon salute.

Within weeks, however, at least three more charters operated by another carrier mirroring its operations arrived in the country bearing throngs of Cameroonians escaping persecution.

According to official figures, 637 Central Africans remain on the island, with depleted finances due to the hefty fees forked out for the December and January flights.

Many are staying in ramshackle homes with sparse utilities at very low rents or cheap guesthouses, while they try to scrabble together funds to continue their journey.

It has created a complicated situation for Antigua and Barbuda which is more used to welcoming tourists than refugees. What most residents are united on is sympathy; to what extent the situation should impact the local landscape with its limited resources less so.

“The government needs to resolve this matter both for the poor people of Cameroon and for the poor people of Antigua,” aviation entrepreneur Makeda Mikael tells the BBC. “Opening up the mid-Atlantic as a migrant route could ruin tourism in the Caribbean.”

The government previously declared its intention to repatriate the refugees. It has since announced a U-turn on humanitarian grounds.

Information Minister Melford Nicholas said a skills audit will be carried out on the migrants to “determine the benefits” of allowing them to stay.

“As the economy continues to expand, we’re going to need additional skills,” he told a press conference. “We will give them accommodation and find a way to give them legal status here.”

He added that the government hoped islanders would “embrace and have an open heart” to the Africans.

Some have done just that, assisting what they see as their ancestral brethren with food, money and a place to stay.

But the government’s stance has not been welcomed by all. Opposition politicians staged a demonstration on 7 February demanding an inquiry into how the situation arose and a consultation on what should happen next.

In the meantime, incoming charter flights from Central Africa have been suspended. Governor General Sir Rodney Williams recently reiterated the government’s pledge to help their African “brothers and sisters”.

He said the country was “committed to protecting all residents from exploitation and harsh treatment”, adding that “no foreign national, except for criminals, should fear deportation”.

Antigua and Barbuda is not the only Caribbean country affected by an influx of Cameroonian migrants.

A few hundred miles away in Trinidad, five Cameroonians awaiting repatriation were granted an 11th-hour court injunction on 16 February preventing the move after intervention by the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR.

Precisely how they reached Trinidad remains unclear but they shared similar stories of arbitrary arrests, torture and death threats in their homeland.

What started as peaceful protests in October 2016 by professionals protesting about discrimination against English-speaking Cameroonians escalated into a bloody conflict when government military forces cracked down.

There are now several armed separatist groups across Cameroon’s two Anglophone regions burning down entire villages and targeting any institution that represents the state, including schools and hospitals, Amnesty International researcher Fabien Offner says.

“It’s definitely one of the worst human rights situations we are covering in the African continent,” Mr Offner tells the BBC.

“Everyone is running for their lives,” Daniel concurs. “Those who are very poor don’t know where to go, they don’t have money to fly away. If some of these children can run to Antigua they should let them.”

Edith Oladele is an Antiguan who used to live in Cameroon.

“Cameroonians are generally a very peace-loving people. They’re just trying to make a better life for their children and families,” she says.

“When we go over there we are welcomed with open arms as the descendants of slaves who’ve come back home. I am praying these people will be able to stay here.”