There’s no doubt corruption hinders economic development. For Africa, corruption is rife and it has completely eroded trust between the public and the continent’s leaders. While there are countless initiatives and organisations already fighting against corruption on the continent, not much progress has been made.

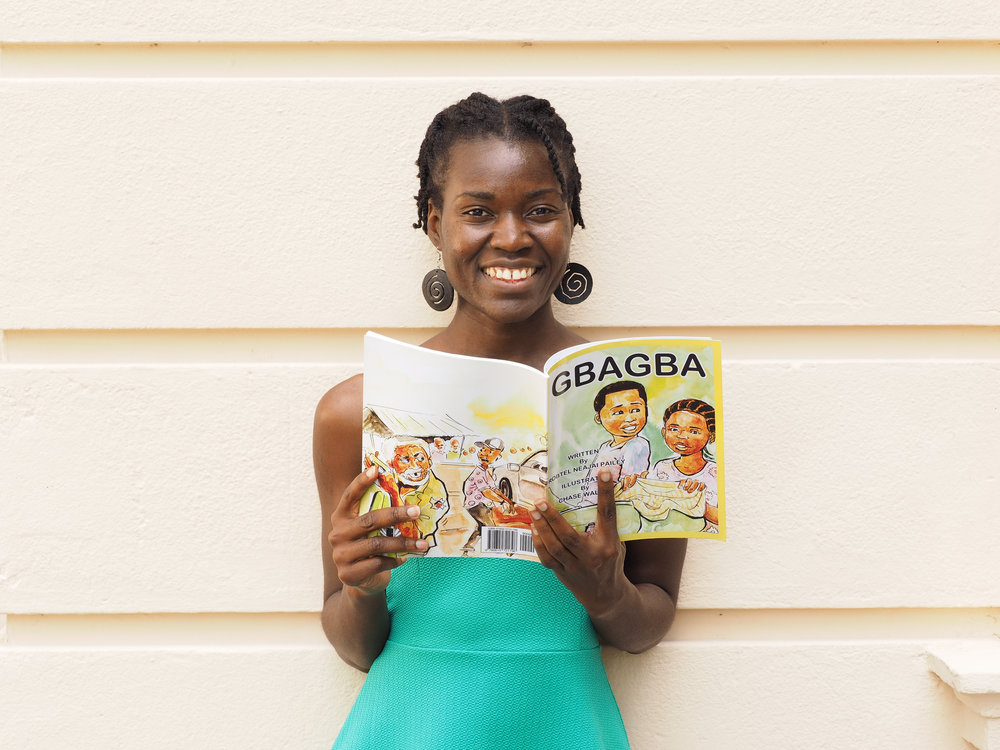

One writer, a children’s novelist, Robtel Pailey believes there is one more way that people involved in the underworld of corruption can be brought to book. She says children are the ‘untapped resource’ of the continent in the fight against corruption.

“I want to bring children to activism because I think children are an untapped resource in the fight against corrution and I think quite often we disregard them in these adult conversations we have about integrity and transparency and corruption and I actually think they are a resource that we are not actually using which is why I wrote the children books.”

Her first book, titled, Bagba which loosely translates to ‘corruption or trickery’ in Bassa, a local Liberian dialect, follows the story of two children who go through experiences on a journey to the capital, Monrovia where they witness things relating to acts of corruption.

“It focuses on the vices of society.”

Her second book focuses on the virtues of society and is titled Jaade which loosely translates to integrity and honesty in Bassa.

“For this one, I really just wanted to focus on the virtues and I think it is important for children to have model behaviour that they can follow and emulate.”

With her two children’s books, she says she wants to help children vocalsie their thoughts on corruption because it is not something they are totally unfamiliar with like adults assume.

“I wanted to give children the verbal tools to really question the ethical codes of the adults in their lives,” she says.

“Quite often we tell children to be truthful and honest but we don’t model that behaviour in the everyday. We instead train children how to be dishonest, we socialise them to be untrustworthy and I think that’s a travesty because I think children have the inherent ability to tell the truth without fear or favour.”

As a literary activist, Robtel believes that corruption should be fought with local languages instead of pure English because it has a huge impact on how information and knowledge is received; something she noticed from another African author, Ngugi Wa Thiongo.

“We almost put the word corruption in ‘linguistic prison’, this is something that I borrow from the Kenyan novelist because when we use the word corruption we are not using it in our own local languages but when you say the word ‘bagba’ it has much more force than the word corruption.

When you use the word jaade, it has more force than the word integrity.

I think it is very important for us to go back to our local languages to describe both virtues and vices in society. I think it’ll force us to think about it much more differently.”

However, not everybody has been on board with the idea to help children understand corruption. Some have said it is too heavy, but she strongly disagrees.

“I’ve done workshops for Jaade in about 12 different countries; some of which are in Africa and the rest outside, and children already know what corruption is. For me, these two books are giving them the tools to articulate it in a way that we can understand.

People ask me why I am targeting children in my stories because they can’t change policy and the response that I give is that the purpose of this is not to change policy.

We have enough policies and regulations on the books on the continent and outside the continent. What I’m interested in is changing values, changing norms, changing the way people interact with one other through very dubious means.”

Her two books, Bagba and Jaade have been adopted by the Ministry of Education in Liberia to be used in grades 3 through 5 (for 8 to 10 year olds in Liberia). The intention Robtel says is to take the books all over the continent and the world.

The Ghana Education Service has incorporated Bagba, the first book, for primary three. She is waiting for responses from other education boards across the continent.

Some of the countries she approached were Kenya, South Africa, Niger, Chad and Cameroon so the processes have already started.