When British TV got its first female black reporter in 1968 some viewers strongly objected and she was sacked in less than a year. Now, half a century later, a British Journalism Award has been named in her honour.

Looking back, how does Barbara Blake Hannah feel about the way the country treated her?

“Too many times you buy a sandwich that you later realise had been spat in, or you’re walking down the street and are spat at yourself, or best case scenario, are told ‘[N-word] go home.’

“But when I roamed the streets as a reporter with a camera, no-one cared that I was black. They just cared about being on TV, that’s one reason why I loved the job.”

Barbara Blake Hannah was 24 when she first arrived in the UK to work as an extra on the 1965 movie, A High Wind in Jamaica. And when filming finished, she and a friend decided to stay.

“Britain seemed to be opening up with opportunities at that time. I was young, living in London during the swinging 60s. It was all so exciting,” she says.

She had plenty of journalism experience from Jamaica, having read the news on TV and written for a magazine owned by her father, Evon Blake, the founder of Jamaica’s Press Association.

But despite this, it wasn’t easy to get a job in the industry. She had to settle for temporary secretarial work “using shorthand and typing skills from training as a journalist”, but she didn’t stop applying for writing jobs, and eventually broke through.

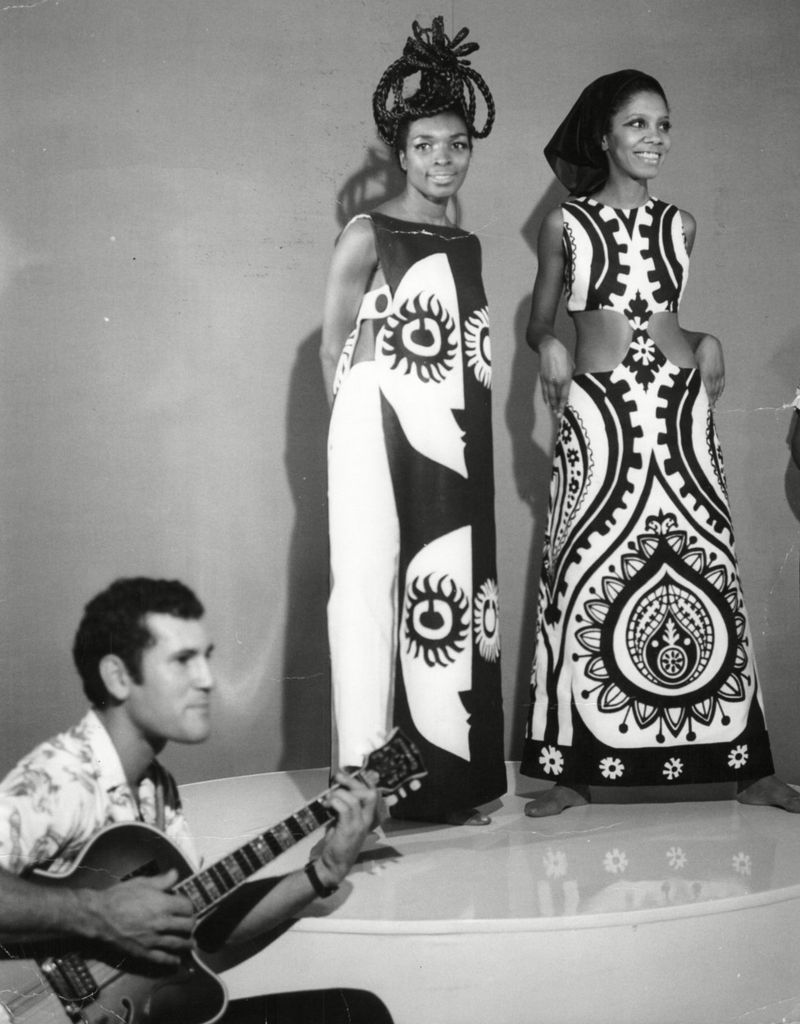

In 1966, Barbara Blake Hannah noticed the Sunday Times magazine was running a series on food around the world, so she got in touch and offered to write something on Jamaican cooking. “I was given a nice colourful page feature in my Jamaican costume,” she says.

This was followed by a number of other plum assignments, including interviewing the A-list entertainer Sammy Davis Jr – the only black member of Frank Sinatra’s Rat Pack – and Jacqueline Susann, author of a 1966 blockbuster novel, Valley of the Dolls, whom Barbara describes as “fabulous, a real superstar, like something out of Dynasty”.

Barbara also wrote for the now defunct West Indian World and Caribbean Times newspapers, and for Cosmopolitan and Queen Magazine.

“It was great to be a young journalist again. I made friends with other writers, we’d go out and about on Fleet Street. There was the Beatles, Jimmy Hendrix, the anti-war-in-Vietnam movement, the play Hair, the Supremes, Tom Jones, Cilla Black… It was fantastic.”

During the summer of 1968, Barbara heard about the launch of Thames Television. In true go-getter fashion, she wrote to them asking for a job, and was asked to audition.

“I was the most interesting, I could write a good script and I made them laugh,” she says. Her impressive French and Spanish skills, which she’d learnt at boarding school in Jamaica, didn’t go unnoticed either. She was immediately offered a contract on the daily evening show, Today, hosted by Eamonn Andrews.

But a black woman reporting the news was unheard of. This was five years before the UK was introduced to ITN’s first black reporter, Trevor McDonald, and more than a decade before the arrival of the BBC’s Moira Stuart.

The Times newspaper did a full-page spread on Barbara’s debut, but she wasn’t fazed.

“To me, it was just another job. I would get briefed in the newsroom, go out to film, come back to edit and be in the studio. I had already gone through the jitters of being on TV during my time in Jamaica, it was just really nice to be able to do what I enjoyed.

“I wasn’t famous like Twiggy, but I guess I was known by a few. It’s only nowadays I hear from people who say they or their parents watched me back then.”

Barbara reported on it all, from crime stories to the closure of the Beatles’ Baker Street shop, often called the Apple Boutique. She interviewed Sir Michael Caine, round-the-world sailor Sir Frances Chichester, and the “great beauty”, Bianca Jagger.

“Eamonn Andrews, though he was famous, was a lovely man and genial host. My colleagues didn’t treat me differently because I was black. In the office, I was just treated as another worker. It was a really great show to be on.”

However, nine months into her role, Barbara’s time at Thames Television came to a sudden end. Her journalistic skills and warm on-screen presence did not impress some viewers who could not see past the colour of her skin. A producer told Barbara that the station had received almost daily requests to “get the [N-word] off the screen”, and so they did.

“It was the most hurtful thing that happened to me because I was black, and trust me, a lot of things happened to me,” she says.

“It was almost as if I had been found to have a communicable disease. I had been so excited to get this job, and now I had to tell my friends I no longer had it, just because I was black. I hid myself in shame for a long time.

“I didn’t receive any compensation, an apology, nothing. I didn’t think of even asking for one, we black people weren’t protected [against discrimination] in the workplace – maybe later on paper, but definitely not in the practical sense.

“But you know what, even just an apology would be nice, 50 years later.”

Thames Television ceased to exist in 2003.

Six months later, Barbara was hired as a reporter for ATV in Birmingham. She says she couldn’t find a hotel in the city that would have her as a guest, so she commuted from London until she discovered she could stay at the YWCA. Some of her colleagues were also less than welcoming, using racial slurs to describe black people in her presence.

“They’d say things like, ‘If we are all so equal, then why didn’t black people create the Mona Lisa?’ But I didn’t speak up. I just didn’t know black history and art then, like Timbuktu and Tutankhamen.

“I remember at a party, a glass cut me and I bled a little. A girl exclaimed, ‘Oh look, it’s red!’ referring to the colour of my blood. Her friends roared with laughter. I was just so embarrassed. I wanted to hide.”

Ignorant and prejudiced attitudes like this seeped into the programme, Barbara says.

“I was once asked to swim a lap in a pool with one of the white reporters. I am a good swimmer, having swum in the Kingston Harbour race when I was 15, but because I was on camera that day I decided to keep my head above water, because I had straightened my hair,” she remembers. But the position of her body in the water as she swam breast stroke with her head up – less horizontal than the body of the other reporter, who swam front crawl – was then presented as evidence supporting a theory that black people can’t swim as well as white people.

The report actually opened with images of her perfect strokes in the pool, and a researcher commenting: “She’s much lower in the water at the back end.”

“I was shocked,” Barbara says.

Barbara on ATV

Some of Barbara’s ATV reports can be watched on the website of the Media Archive of Central England (search for Barbara Blake), including:

- The swimming report, where Barbara and a colleague interview an academic who thinks black children may be physiologically less capable of swimming

- Bad housing – Barbara visits a homeless family housed in a damp building on a former military base

- Barbara enjoys questioning female passers-by on the streets of Birmingham about their problems with poorly manufactured tights

One of the worst moments at ATV was when she was sent out filming on a bitterly cold day, only to be told later it was because Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell – fresh from his anti-immigration Rivers of Blood speech – had agreed to do an interview at the studio on condition that “the black girl” was not there.

“I was a little upset, but that was to be expected from him. He was a pretty scary man. Looking back, I wished I’d been around to ask him some very tough questions.”

ATV ceased broadcasting in 1982.

Barbara was glad when her six-month contract came to an end. She then moved behind the scenes, working as a researcher on the BBC documentary series, Man Alive, after much encouragement from editor Desmond Wilcox during a job interview. “It was the best job I had in TV. People were pleasant and we did some really nice stories, including a one-hour documentary at the Cannes Film Festival, which opened the door for me to go back to Jamaica.”

After the documentary aired, she was asked to help promote the 1972 movie, The Harder They Come, starring reggae legend Jimmy Cliff – often described as Jamaica’s first feature film. For Barbara, it seemed like the film was calling her home, and she decided to move back to Kingston later that year.

“The film blew my mind. It showed me a culture and country that I didn’t know existed. The reggae and the Rasta world, which wasn’t part of the life I’d experienced there before. I felt that was an opportunity for me to see a new Jamaica. The real Jamaica,” she says.

She continued working on films and attended film festivals around the world, including one in Iraq hosted by President Saddam Hussein. She also wrote books, including Rastafari – The New Creation, inspired by her new religion, and her 1982 memoir on her time in Britain, Growing Out: Black Hair and Black Pride in the Swinging Sixties. She continued reporting for Jamaican publications, and interviewed the likes of Cuban President Fidel Castro and UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson – annoying the latter with questions about Rhodesia’s declaration of independence.

From 1984-1987, Barbara served as the first Rastafari senator to sit in the Jamaican parliament. It was during this period that she gave birth to her only child, a son.

“He tells me every day, ‘I’m so proud of you mummy.’ We’ve had some hard times together, but we made it through.”

Barbara has only visited the UK three times since 1972, for very short spells. This included a 1983 trip to make the documentary Race, Rhetoric, Rastafari for Channel 4, which explored Rastafari beliefs and race relations in England.

Now 79, watching the UK from afar, she says it seems clear to her that systemic racism remains a problem.

“People still have the same attitudes,” she says. “Look at how shocked people were when Harry, the most loved member of the Royal Family, married a black woman.”

But she was excited by the recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations, including the toppling of the Edward Colston statue by demonstrators in Bristol.

“When I saw that statue come down I thought, ‘Oh my goodness!’ I just had to smile and clap. I am part of a generation that was brought up to humbly obey and accept racism, so I am glad to see our next generation are not putting up with it any more.”

Barbara’s accomplishments continue to be recognised on both sides of the Atlantic. In 2018, she was honoured with the Order of Distinction by the Jamaican government for her contribution to culture.

In the UK, the Press Gazette this year introduced a Barbara Blake Hannah Prize to its annual British Journalism Awards. It is to recognise emerging journalists from black, Asian and other ethnic minority backgrounds and will be awarded for the first time in December. Barbara has ensured that the winner will receive a free trip to Jamaica, if the pandemic allows.

Barbara hopes the award will help address the lack of diversity in the British media. According to a 2016 Oxford University survey, only 0.2% of journalists in the UK are black, despite black people making up 3.3% of the population.

If you include Asians and other ethnic minorities too, there is still a disparity, though not quite such a large one; 6.3% of journalists come from one of these backgrounds, compared with 14% in the general population.

“What happened to me 50 years ago has now turned into something that will recognise and create opportunities for young black journalists today. This is the most rewarding thing to have come out of my career.

“I want those who hear my story to know we still have a long fight ahead of us, but remember you have the same right as anyone else to be where you are. Don’t allow yourself to be stereotyped. Be confident in yourself. Fight for yourself to be included.”