The colonial era put a whirl spin on true cultural identities by teaching schoolchildren in English, ignoring Kenya’s several languages including the widely spoken, Kiswahili. By the time of independence, mother-tongues were at risk of fading into history’s past. But one man, Dr. Henry Chakava set out to translate African books and educational material written in English to give children access to all languages spoken in Kenya.

“At that time, there was no publisher publishing in English locally, there was no publisher publishing in Kiswahili and there was no publisher publishing in the local languages.”

In 1972, Henry Chakava graduated with a double first and was about to pursue an academic career abroad. To kill some time before beginning a scholarship-funded study, he took a temporary job in Heinemann Publishers which had opened a new office in Nairobi.

It was a decision with lasting consequences.

“Well it changed my life in the sense that I was supposed to be at Heinemann for about three or six months and I stayed there forever.”

Henry Chakava became the first ever Kenyan editor at Heinemann. In the 1960s, Heinemann had developed the African Writers’ Series championing the work of writers such as Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiong’o. But until that point it had all been written and printed in English. When Heinemann ceased to publish the African writers Series, Henry Chakava took up the East African regional list and played a crucial role in changing African publishing.

“We had decided consciously to launch the Kiswahili series from the books which were published in the African Writers series. So it was when people started seeing books appearing in Kiswahili that they said ‘well we can give you some original works which you can also publish in the same series’. We were receiving a lot of manuscripts coming in and in fact, more than we could handle. So my job was to go through all these manuscripts and come up with a few that we could consider for publishing.”

Kiswahili or swahili is widely spoken in many countries through Eastern, Central and Southern Africa. Historically it was the language of commerce which accounts for the number of words borrowed from Arabic, Persian, and even Portuguese picked up from traders sailing up and down the coast. In fact the first known written examples of it are in the Arabic script but European colonialists introduced the Latin alphabet and standardized the Kiswahili which did help to cement it as a tool for international communication.

When countries in the region gained their independence, it made sense to promote Kiswahili as an official language of government and education. But English remained dominant.

“There were a lot of white people around. For example, in secondary school I was educated by white people. Most of the teachers there were white and even in the civil service we still had quite a number of white people. In fact as I entered publishing, I also found a lot of white people in the industry. So in the 60s’ it was a transition between white people to the black people. There was what we call ‘Africanisation’.

Henry Chakava decided very early on that publishing in Kiswahili whilst groundbreaking in itself didn’t go far enough. So he decided to start publishing in other regional languages too.

“I felt that all these languages were important and they needed to be given their rightful place. Language is our culture, language is the best way to express ourselves, you grow in language. So it is very very important for one to learn to write and to speak in their own mother tongues first.

My first three years of primary school were taught in mother tongues and I was able to grasp my mother tongue completely before I could start with Kiswahili and then English. If a child is introduced to education in a foreign language as the primary language of learning I think that they completely lose grip of their culture. They get lifted into an environment which is not theirs.

I think they lose their identity completely. They don’t have that wholeness of their personality. Why do they start speaking their different languages before they master their mother tongues? African languages are important and they need to be taught, they need to be developed and it doesn’t take too much to give them room to just reveal themselves.”

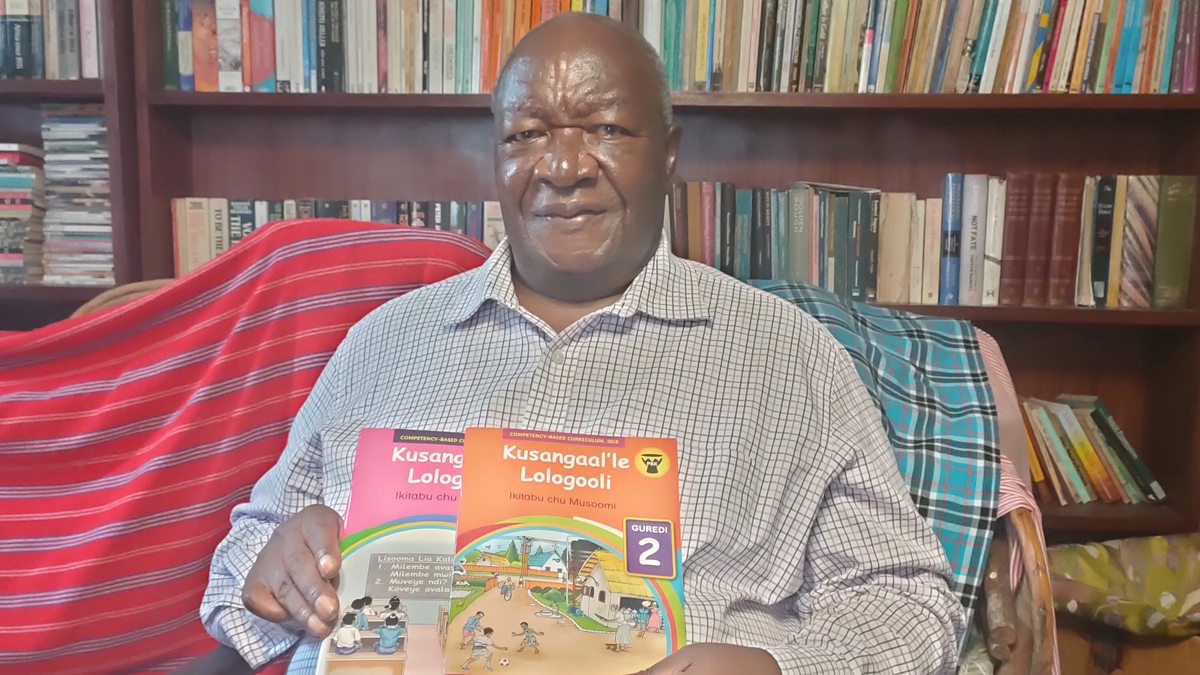

Henry began producing books and other educational material in several of Kenya’s languages including his own.

Whilst the government encouraged the learning of mother tongue in early education, there were no textbooks, no curriculum, nothing to introduce a child to the written form of their own language, even in Kiswahili either. But it wasn’t just in early education that there were discussions about writing African languages.

In the mid-70s, Kenya’s most famous writer and Henry’s former university Professor, Ngugi wa Thiong’o made what was seen as the political choice to write primarily in his mother tongue, Kikuyu. It was deeply controversial. Kikuyu is spoken by one of the large groups in Kenya. Ngugi was writing plays and pieces about corruption and political misconduct and in a language that ordinary people could understand.

Henry was publishing them and they soon both fell foul of the authorities.

“I was there with him from the beginning; all these discussions we had together. Some that he wrote would never have seen the light of day had I not published them,” Henry Chakava said.

Ngugi was detained by the authorities shortly after beginning to write in Kikuyu because it was considered that radical and subversive to write in his own language.

“After Ngugi left detention I gave him space in my publishing house; I gave him a chair and desk and he was sitting and doing his writing. Books that he wrote like ‘Ngaahika Ndeenda’ which means ‘I will marry when I want’ he wrote them in my office and it was considered very dangerous to publish him.

“In fact, it was very dangerous to associate with him.”

“I was also tortured in fact because of my stance on publishing Ngugi. I was attacked at my gate and beaten up. I knew. I knew it had something to do with the authorities. They would ring me and they would threaten me and tell me not to continue to publish Ngugi. They would come and collect all the books in stock, they’ll take them away and I will still bring in some more. I think that emphasizes what language can do because while he published in English he was not considered so controversial.

I didn’t fear. I actually feel I wasn’t exposed to so much danger until it happened but I didn’t want to stop. I continued. I believed that I had to publish those books, they needed to be published and who else will publish them?”

Henry Chakava’s experience proves how important speaking the authentic language of the people is. If it wasn’t it wouldn’t have been so politically dangerous.

“That is the contradiction because if the politicians seeking office they use the authentic languages to campaign, but when they go to parliament they start speaking english,” he laughed.

Dr Henry Chakava has been frequently called the “Father of Kenyan Publishing” and in 2006 was awarded by the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development for his contributions to African publishing and the promotion of African Literature and culture.