Hadizatou Mani-Karoau was sold off to a local chief, aged just 12, to become a wahaya or “fifth wife”.

“It was a terrible life. I had no rights; not to rest, not to food, not even to my own life,” she tells BBC 100 Women from her home in southern Niger.

Wahaya is a prevalent form of slavery in her region, where wealthy men buy young women for sex and domestic work for as little as $200 (£170) and make them fifth wives to circumvent Islamic law, which allows for a maximum of four wives.

Ms Mani was sold in 1996 and spent 11 years as a slave.

But her ordeal didn’t end there. After being freed in 2005 and marrying a man of her choice, her former enslaver sued her for bigamy and Ms Mani was sentenced and jailed while pregnant.

Eventually, more than a decade later, her conviction was overturned. Hers was a landmark case in Niger, where slavery has persisted despite continued efforts to outlaw it.

Now Ms Mani lives her own life in Zongo Kagagi, a town in Niger’s southern Tahoua region, and campaigns for other women to understand their rights and escape slavery.

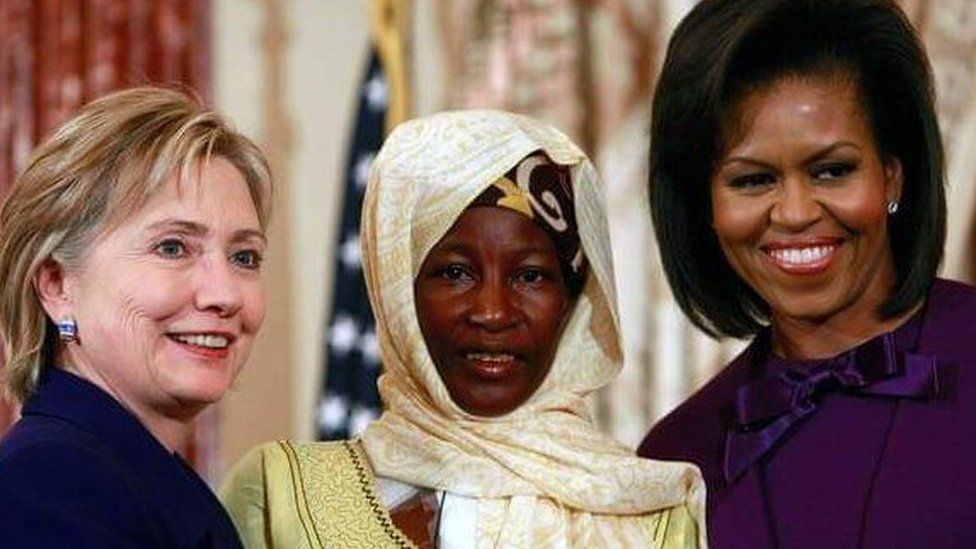

She is one of the women featured on the BBC 100 Women list, which each year names 100 inspiring and influential women around the world. This year the list is honouring the progress that has been made since its inception 10 years ago.

Ms Mani’s case was instrumental in getting legislation changed in her home country.

Yet despite court rulings, and Ms Mani’s campaigns, more than 130,000 people are still enslaved people in Niger today, according to Global Slavery Index figures.

The extra wife

“Fifth wives” are enslaved by wealthy men in the region, and are also given away as gifts under an associated practice known as sadaka. Both wahaya and sadaka are considered forms of sex trafficking.

These fifth wives are, in essence, concubines enslaved to their master, the master’s legal four wives – whom he would have married in accordance with Islamic law – and their children.

They are subjected to mental, physical and sexual abuse, are frequently denied food and other basic necessities, and forced to work doing house chores, tending to livestock and cultivating crops.

This was Hadizatou Mani-Karoau’s life after she was bought in Niger and taken across the border to Nigeria.

She says the influential chief “got a good bargain” for buying her and seven other women and girls at once. The transaction was made without her or her parents’ consent.

A vicious cycle of abuse saw her run away back to Niger on more than one occasion, but each time she would be captured and brought back to Nigeria to face even harsher punishment.

“He would say that he could do with me as he pleased because he bought me just like he bought his goats,” she says.

She was raped and forced to bear her enslaver’s children.

The wahaya practice dates back several centuries and is deeply entrenched in society.

French colonisers banned it in the early 20th Century, but frequently just ignored it rather than prosecuting the perpetrators.

In 1960, under Niger’s new constitution, slavery was once again outlawed on paper – but allowed to continue in practice.

The country eventually took a significant step in 2003 by formally defining wahaya and criminalising it under the penal code.

Following this ruling, Ms Mani was granted her certificate of freedom and in 2005 she walked out with her two children and two fellow wahayou, to live again as a free person.

But when she went on to marry her current husband, a year later, her former enslaver took her to court and sued her for bigamy, maintaining that she was still married to him.

The ‘triangle of shame’

Ms Mani was found guilty of bigamy and sentenced to six months in prison – a ruling that would be overturned only in 2019.

However, she also went on to file a case against the government of Niger at the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), that led to a landmark judgment.

Judges ruled that Niger had broken its own anti-slavery laws by not convicting the man who enslaved her, and failed to uphold its legal responsibility to protect her.

She was awarded $20,000 (£17,000 or 10,000,000 CFA francs) in 2009, which the government of Niger paid.

Ms Mani was aided by Niger’s anti-slavery organisation Timidria and British NGO Anti-Slavery International in her fight for justice.

Timidria Association president Ali Bouzou says slavery is still rife in the regions of Konni, Madaoua-Bouza and Illela, an area they have branded “the triangle of shame”.

“There are entire villages in ‘the triangle of shame’ where more than half the population is made of wahayou,” he says.

Some prosecutions are taking place in Niger, under the anti-slavery legislation.

Between 2003 and early 2022, there have been 114 slavery complaints, Mr Bouzou says, out of which there were 54 prosecutions and six convictions (four of these were suspended).

But this legal battle is far from won. Those found guilty of slavery-related offences are supposed to receive jail sentences of between 10 and 30 years, but recent convictions have been much shorter, at under 10 years.

Experts are calling for broader measures to tackle the issue. Mr Bouzou’s organisation recommends that traditional chiefs – who are often behind the practices – should be stripped of their powers. It is also calling for efforts to challenge the widespread misconception that wahaya is in line with Islamic law.

Meanwhile slavery remains a global problem.

Prof Danwood Chirwa, Dean of Law at the University of Cape Town and chairperson of the United Nations Trust Fund on Contemporary Forms of Slavery, says slavery has been on the rise in recent years and made worse by the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

He quotes a 2022 report by the International Labour Organization, the International Organization for Migration and Walk Free that shows that there are 50 million people living in enslavement globally, with seven million of those being from Africa.

“The war against slavery has become difficult because African countries do not legislate against it in all its forms in their individual territories, despite fulfilling their international obligations,” says Prof Chirwa.

Today, Hadizatou Mani is a happily married mother of seven children between the ages of one and 21.

She has helped many women, including her own sister, escape slavery and live free and productive lives.

“I especially teach these women about their freedoms as safeguarded by the law,” she says.

“I do not regret a single thing that happened to me… It wasn’t in vain, my plight highlighted the issue of wahaya to the world.”