As a child he knew both love and violence; as an adult, both recognition and rejection. The writer talks about his marijuana-dealer father, his clashes at the BBC and the police stop-and-searches that drove him out of London

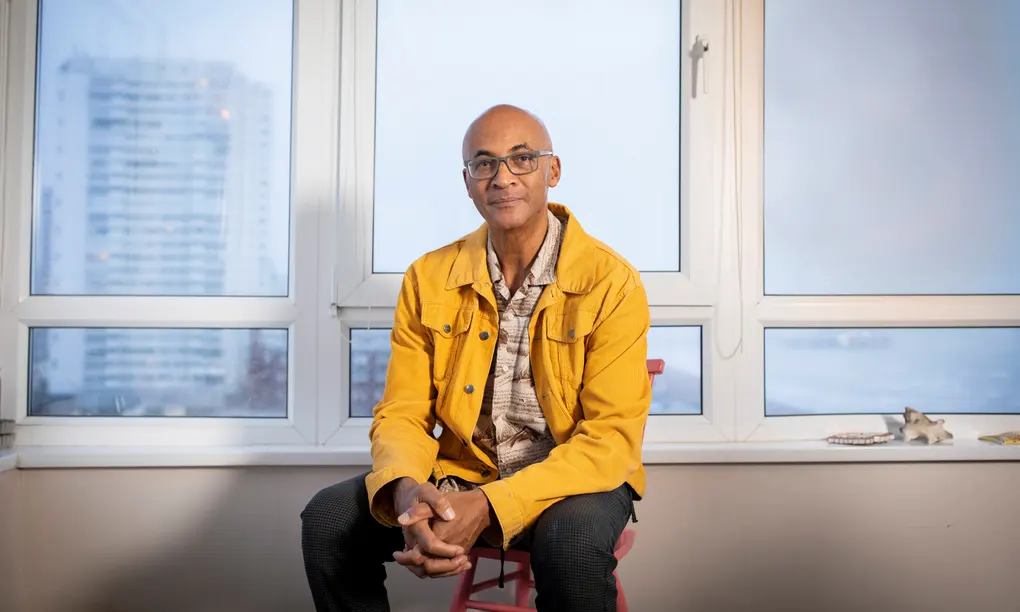

Colin Grant describes himself as a British historian and writer, but one with a Jamaican will and inclination. What he means by this becomes clear over our 90-minute conversation in his Brighton seafront flat. Discussion centres on questions of identity: why do working-class parents often fear their middle-class children, why do former colonies continue to fetishise “Britishness”, and why does he think spelling black with a capital “b” is political correctness gone mad? “I think it ratifies this idea that your so-called race precedes you … In Jamaica, we say: ‘All a-we is one.’”

When it comes to arguing the semantics, Grant is even and surgical, which is apt for a man who turned his back on a promising medical career to pursue writing. But he is also mischievous and stubborn, traits that he has surely inherited from his parents, who share top billing in his new memoir, wonderfully titled I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be.

“I’m glad you like the title,” he says. “I’ve been nervous about it. I’m not saying I dislike being black. I’m just saying that being black comes with certain kinds of challenges.”

It is particularly provocative given the audience for his books and journalism is overwhelmingly white: was it a direct challenge to many of his readers? “Well, yes. But hopefully it’s going to provoke them to think about what that sentiment might mean. It’s introducing people who may not be familiar with the life of a black person to some of those challenges.”

In any case, Grant feels he is now brave enough, “or old enough”, at 61, to quit being nervous about how his writing will be perceived. Instead, he wanted to give the reader, regardless of their race, what he calls “the black nod”: “that subtle and secret signal one black person would give whenever they saw another on any British street,” he writes in the book’s opening chapter. “If people get it – they get it. I’m not going to dilute it any more,” he says.

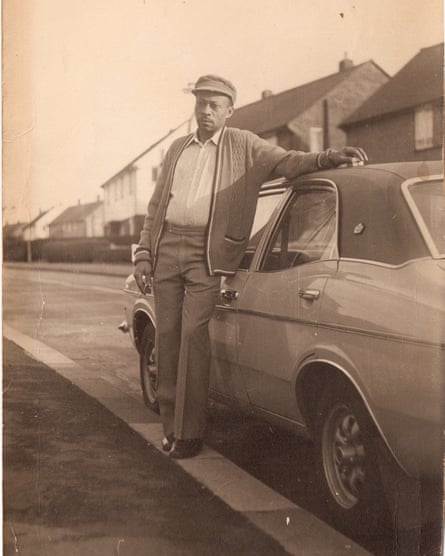

While the title – and Grant’s tough talk – might sell his book as a polemical state-of-the-nation manifesto about race and identity, its setting is specific and personal: Luton in the 1970s, a complex, multiracial landscape populated by engaging characters. The most notable of which were Grant’s mother, Ethlyn, a Caribbean matriarch with a “martyrdom complex”, always on hand to provide love and maternal support to her seven children; and his father, Bageye, a charismatic ganja dealer with a violent temper and the belief that fatherly wisdom should be accompanied by “the belt”.

Bageye (so-called for the permanent bags under his eyes) was a “world class beater”, says Grant, although his perspective now is that his dad was probably trying to do him a favour. In his book, he writes: “The logic was simple: we were under surveillance in Britain. If his ‘pickney’ didn’t absorb the lessons of the proportionate ‘licks’ meted out by him, then we were liable to suffer the malicious consequences of a far more punitive state.”

While curating his 2019 book Homecoming, on Caribbean migration to Britain, Grant heard again and again of people who received this kind of punishment as children in the 1970s and 1980s. It is troubled logic: better I beat my kids with love than the police beat them with hate. But it speaks to the paranoia and fear that stalked black Britain during the era. “I don’t know whether my father would have intellectualised it in that way,” says Grant. “I think his beatings were just born of ignorance and frustration. Bageye was a tyrant who ruled through trauma and pain.”

I ask if he ever felt guilty about revealing the trauma his father inflicted in such a public way. Grant has six siblings and his pain is presumably shared and complex. Plus, as he notes in the book’s introduction, “Jamaicans are the most litigious people on the planet.” “Well, you can’t libel the dead!” he chuckles.

The trauma contained within the book is frequently accented with humour, and you can imagine him laughing while recalling his days as a 10-year-old bagman for his father, cheerfully handing out ganja to all his loyal customers. “I will say that my education was funded by marijuana. I think he came to Britain with his love of ganja intact and he thought he was providing a social service!”

Ethlyn showed Bageye the door when Grant was 13, but he remained at St Columba’s, a private school in St Albans (“It was a Catholic school and I think my mother shamed them into giving me a free education”). He went on to be head boy, before studying medicine in London.

In truth, though, Grant never had an appetite for a medical career. His father had sat him down at the age of 10 and told him he would be a doctor. Fear and ignorance prevented him from ever really questioning the idea.

His days as a medical student did, however, lead him to his wife, Jo Alderson, whom he met when their mutual friend Victor – now Lord Adebowale – invited them both to a literary cabaret.

Four decades on, they have three adult children, Jazz, Maya and Toby, and live together in this flat with a wonderful view of the coast – little wonder that Dickens would stay in this block during his many seaside excursions to work on his novels. Was it Brighton’s literary history and abundance of grungy writers’ cafes that inspired the move from London?

“I came because I got fed up with being stopped and searched in London by the police,” Grant says. In his book, he recounts being stopped while returning from a late shift at the BBC for “having cobwebs on his bumper”. He notes the paradox of being black in Britain: at once invisible in the upper echelons of parliament or the professions but also in danger of being “hypervisible, especially to policemen on the street, when all you wanted to do was to go about your business unmolested”.

Although Grant’s freelance night shifts in the newsroom would lead to an enviable career at the BBC as a TV script editor and radio producer, the most painful chapter in his memoir is about his time there: Grant has the record for the most disciplinary hearings ever brought against a BBC employee (four). One of the vague charges was: “a pattern of behaviour which might be regarded as aggressive [and] can be perceived as hostile, in terms of your tone of voice or body language”. It is hard to know the truth of it – whether his face just didn’t fit. “Even my worst enemy – I wouldn’t wish a disciplinary hearing on them,” he says.

His goal in the chapter was not just to rub salt in a few old wounds (no names are really named) but to “show that the BBC is a microcosm of society … You’re on trial for not really being part of the tribe.”

While his British core still bristles with pride at what the BBC represents and the role he played within it, he harbours animosity about the way it chewed up and spat out a generation of talented people of colour. “The BBC is an amazing institution but it’s full of extraordinarily timid people that lack the courage to put their head above the parapet and say: ‘Something’s wrong.’” (The BBC declined to comment on Grant’s allegations.)

The experience also taught him that he was more Jamaican than he had realised: “Maybe I was a bit ‘kissing my teeth’ and ‘raising my eyebrows’, but what’s become clear is that there’s been this huge disparity in the ways that people are paid; women are paid less than men … and it’s like, with the passage of time, the veil’s come off.”

He notes that, while there have been some notable successes for the BBC since his departure in 2018, including Small Axe and I May Destroy You, the numbers are limited.

“I always argue that the reason there are so many versions of Dickens or Arthur Conan Doyle is because a lot of the time these white commissioners are wanting to recreate their childhood,” he says. With the 75th anniversary of the Empire Windrush’s arrival in the UK in mind, he suggests that Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners is ripe for adaptation. He says the kind of characters that populate Selvon’s books are something he wanted to incorporate into his own: “wonderful, individualistic, colourful Caribbean men and women”.

Grant sees the Windrush anniversary as a great opportunity to celebrate the contribution of Caribbean migrants, and “to recognise that actually it’s a shared story … People often argue that there’s no such thing as black history. There’s history.” It could, he says, be “a very unifying moment – a chance to say: ‘This is British history,’ and not confine it to one month in October”.

Unfortunately, it will probably descend into an excuse for race-baiting headlines and machine gun shrieks of, “What about the white working class?” As Grant says: “There is a feeling among certain rightwingers of, ‘When are they going to be satisfied with what we’ve given them?’” He resists defaulting to an easy denunciation of the bad guys, instead harking back to his favourite Caribbean phrase: “All a-we is one.”

Ultimately, buried in Grant’s title is not bitterness about his own lot but angst about whether he has made the most of the opportunities afforded him by the sacrifices of others. Woven throughout is the understanding that his parents had to do the heavy lifting to make his life easier; they were black so he didn’t have to be. His admiration for the way his mother channelled her own sense of dislocation into maternal support makes for one of the book’s most moving chapters.

On a trip to Jamaica with her, he was struck by the ease with which she communicated. “Growing up with her in Luton over the years, I’d observed how she became so fed up with English people saying ‘Pardon?’ to her whenever she opened her mouth that, after a while, she stopped speaking altogether,” he writes. “Conscious of her accent, whenever the phone rang, Ethlyn no longer answered but just handed the receiver to me – her child interpreter/translator. Now she spoke freely, as if restored to her mother tongue.”

“I wanted to show that, yes, there is this colour, this joie de vivre among Caribbean people, but it sometimes comes at a cost,” he says. “The idea that you’re going to better the lives of your children, educationally and maybe financially, at the expense of the kind of rich emotional life that you might have had if you’d remained back home in the Caribbean.”

Grant has used his knowledge and passion for black history to give his children an education that is still largely absent from British schools. “My kids can quote chapter and verse about Marcus Garvey, Bob Marley, Peter Tosh … and by exposing them to this notion of history of black people, including Bageye, I’ve reached both the older generation and the younger generation too.”

While the main event of Grant’s memoir is inevitably the reckoning with his forebears, his focus now is on ensuring there are opportunities for a new generation of writers of colour. Grant is director of WritersMosaic, a division of the Royal Literary Fund, and he namechecks gal-dem and the Everyday Racism Book Club as being part of a rising tide of young writers and activists.

“What’s happened over the last few years is unstoppable; the good genie is out of the bottle,” he says. “And there’s no way they’re gonna put the stopper back in.”