From sleeping rough in Paris to being cast as a slave three times in five years, the Shazam! star is no stranger to hardship. Will Hollywood finally give him the great roles he so clearly deserves?

The extraordinary story of Djimon Hounsou began in the 70s with a weekly hunt for five empty Omo detergent sacks. The prize on offer: one free ticket at the local cinema in Cotonou, Benin. The recycling scheme made the cinema the place to be every Wednesday, when Hounsou and his schoolmates had the afternoon off, so tracking down the packages was a priority: asking family, door-knocking neighbours and riffling through rubbish. Regardless, every Wednesday afternoon, the cinema was rammed.

“You’d have the theatre packed all the way to the bathroom; all kids,” says Hounsou. “I remember vividly: sometimes you would be in the back of the theatre and you couldn’t see the screen. But you could hear it. These were cowboy films coming from America and all you could hear were the shoes and the spurs. The sounds were like a dagger; it really pierced your inspiration.”

Hounsou began to dream of becoming an actor. “The dream was just so big that I went all the way to America and forgot that I didn’t speak English!” he says.

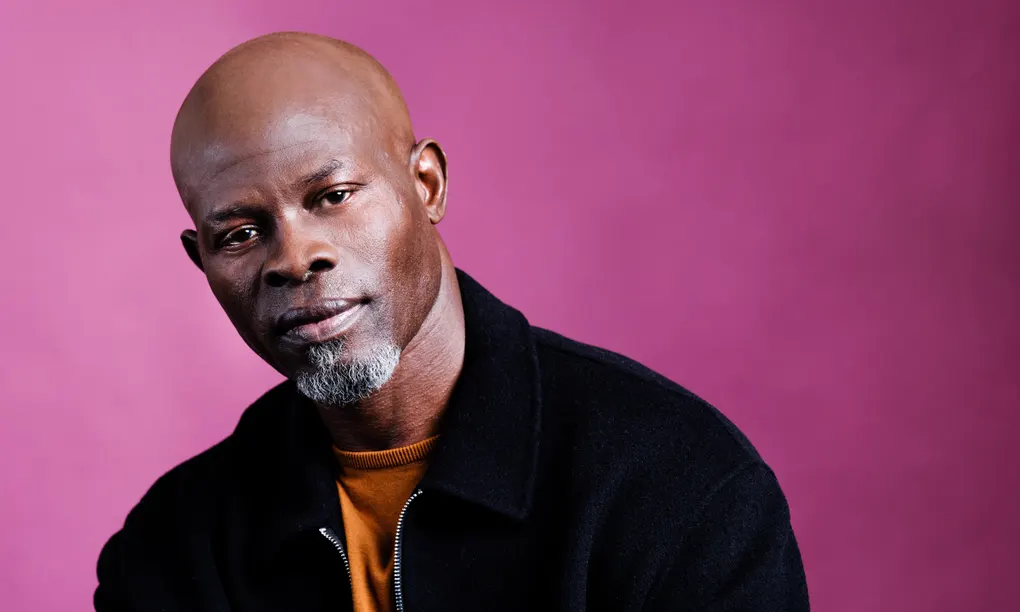

Today, Hounsou’s dream has brought him to London to discuss his latest role, the Wizard in DC’s latest superhero instalment, Shazam! Fury of the Gods. He is 58, but his distinguished, grey goatee is the only mark of ageing. He sits on the sofa with almost regal poise, hands clasped in his lap. Before we start, he pulls the recorder closer; he speaks with a soft, low rumble, at times barely a whisper.

For Hounsou, realising his dream has been a constant struggle. His story wouldn’t be out of place on the silver screen, moving from his family home in Benin to living on the streets of Paris to becoming the first Black African actor to be nominated for an Academy Award. He has been a fixture of critically acclaimed dramas and big-budget blockbusters for more than 25 years, but there is the feeling that in a different, more open, era of film-making, he might have gone even further.

Hounsou describes his early life as “not the best childhood you could wish for a young man”. The youngest of five siblings, he was an introvert, but embraced the escapism of performing in school plays, all the while keeping his grander thespian ambitions hidden from a family with more middle-class aspirations.

Early on, his mother and father, both cooks, moved to Ivory Coast for work, leaving one of Hounsou’s brothers to raise him. At 12, it was decided that Hounsou would go to Lyon, France, to live with his older brother Edmond, who had become a French citizen. “It’s a different environment that taught me so much, but it also ripped me apart,” he says. “I was extremely lonely. There was nobody I could connect to. You’re in a completely foreign environment, an environment that is seen to not care much for your kind.”

His brother was “just barely surviving”; Hounsou, who had obtained a student visa, was often left on his own. “We ended up living in a room half the size of this” – we are sitting in a modest hotel room – “just with a narrow bed and no shower and no bathroom.”

By 19, Hounsou knew he was never going to work in an office – he wanted to make movies, or at the very least get into professional boxing, his second passion. He told his brother he was going to leave school. “Long story short, he reported back home to our parents.”

Hounsou was ordered to return to Benin (his parents had since moved back) for a dressing down. He did, but made sure to get a return ticket. “I got off the plane and I could see the face of my mum and I was like: ooh, this is about to be a rough three months!” he says. “They were just really mad and disappointed that they sent their son all the way to Europe, to white-men country, and I came home with some fucked-up ideas about being a boxer or making movies.”

They also weren’t happy about him insisting on going back to Lyon. “I really had to stand my ground and challenge anybody to come and get the return ticket off me.” When he did return, his boxing hopes were quickly extinguished after he endured a few knockouts. His relationship with his brother soured and he was kicked out of the apartment.

Hounsou didn’t hang around. He moved to Paris, but acting work was hard to come by (“I felt the racism was quite heavy out there back then”). Before long, his student visa had expired. “Not only am I homeless, but I’m also illegal,” he says. “It was almost impossible to live and to find a job in France at the time. So that’s how I ended up on the streets.”

He slept on park benches. During the day, he would ride the Métro for warmth, or hang out by the Pompidou centre, sleeping in its library. One day, while in the adjacent square, he was approached by “a very feminine gentleman, who was like: ‘Oh, you have a cool look; I have a friend who’s a photographer who’s looking for really cool faces,’” says Hounsou. He took the man’s card, but he didn’t have the money to make the call. He was worried about the man’s motives, but, when he came back, “the desperate need to eat or to be in a warm shelter made me follow him”.

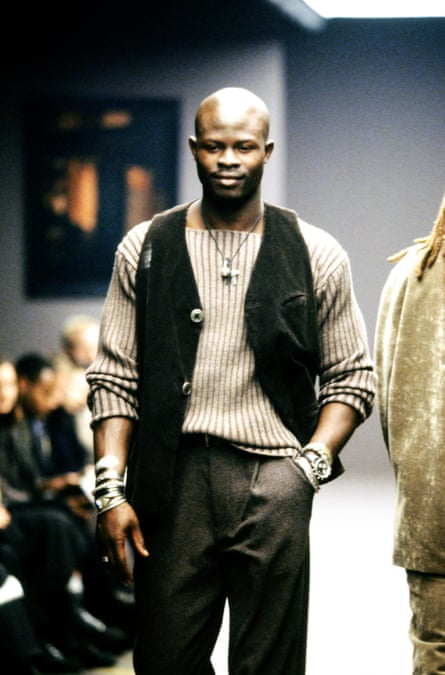

The man’s offer was legitimate. A shoot was organised the same day; within the week, he was auditioning to be a model in front of the legendary designer Thierry Mugler.

“He immediately saw me and was like: ‘This is who we’re looking for. This is the man.’” It was an alien, stressful environment. Mugler’s assistant took pictures of Hounsou in different outfits, including some leather underwear.

Did he feel uncomfortable? “Oh, for sure, I was very uncomfortable and not sure if this was a disservice to my manhood,” he says. “But at the same time, certainly, Thierry Mugler could feel I was very timid about this setting and was a gentleman who put me at ease.”

Hounsou enjoyed success as a model in Paris. After 18 months of being homeless, sleeping rough even during his first few jobs, he finally secured an apartment. As well as Mugler, he collaborated with the likes of Iman, Naomi Campbell and the celebrated photographer Herb Ritts. But it wasn’t his passion. “I certainly didn’t feel like I belonged in that world,” he says. So, at 22, he moved to Los Angeles, despite his limited English.

“All I knew how to say was: yes, hello, good morning, thank you, yes sir,” he says. A visiting friend mocked his Hollywood ambitions. “‘Acting? But you realise you don’t speak the language?’ For somebody else to point it out was like a slap in my face,” he says. “I was so hurt; from that point on, I refused to tell anybody my dreams.”

Undeterred, Hounsou continued modelling in LA and taking parts in commercials, to make enough money to pay for his acting and diction classes. He landed roles dancing in music videos for Janet Jackson, Paula Abdul and Madonna, as well as picking up small film roles.

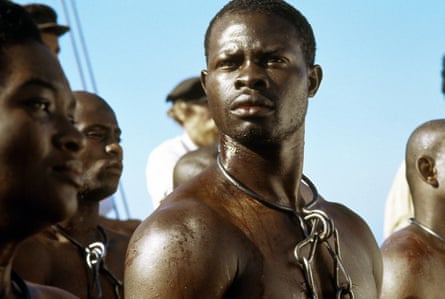

Then came his audition for Amistad, Steven Spielberg’s 1997 historical drama about an uprising on a 19th-century slave ship. The casting director asked if he spoke any African languages. He did: his mother tongue, Goun. He was asked to deliver the audition in it. “I was taken aback, because I had spent so much time trying to articulate this in English.”

Later, he was called in to meet Spielberg. “And I was like: ‘Whoa, what the fuck!’ And my life changed dramatically after that.”

Amistad was Hounsou’s Hollywood calling card. The New York Times said his performance gave the film “a strong visual focus as he radiates extraordinary presence and fury”. But despite the widespread acclaim, one body that failed to notice his performance was the Academy. His co-star, Anthony Hopkins, was nominated for best supporting actor, but Hounsou was overlooked.

That must have been infuriating, I say. “Yeah. Maybe I was early. If my movies had come out today I definitely would have gotten an Oscar already,” he says.

Hounsou was at least nominated for his later performances in In America (2002) and Blood Diamond (2006), although in the latter Leonardo DiCaprio received a nomination for best actor while Hounsou had to make do with a nod for best supporting actor, despite the film focusing on his character’s story.

“I felt seriously cheated,” he says. “Today, we talk so much about the Oscars being so white, but I remember there was a time where I had no support at all: no support from my own people, no support from the media, from the industry itself. It felt like: ‘You should be happy that you’ve got nominated,’ and that’s that.”

He was frustrated with the limited parts Black actors were being offered. He played a slave three times in five years (in Amistad, Gladiator and The Four Feathers). Does he still find the industry limiting?

“I’m still struggling to try to make a dollar!” he says. “I’ve come up in the business with some people who are absolutely well off and have very little of my accolades. So I feel cheated, tremendously cheated, in terms of finances and in terms of the workload as well.

“I’ve gone to studios for meetings and they’re like: ‘Wow, we felt like you just got off the boat and then went back [after Amistad]. We didn’t know you were here as a true actor.’ When you hear things like that, you can see that some people’s vision of you, or what you represent, is very limiting. But it is what it is. It’s up to me to redeem that.”

Hounsou lives in Atlanta with his partner Ri’Za and his one-year-old son, Fela (he has another son from a previous relationship). Since Blood Diamond in 2006, he has mostly played bit parts, sidekicks and henchmen in various action and superhero franchises, including Marvel, DC, Kingsman and Fast & Furious.

It is not how he would want it. The reason for taking so many smaller roles, he says, is to assert himself as a “man of today” and “to prove that I can speak the language. I may not speak perfectly like an American with an American accent, but I don’t need to be all-American,” he says, slipping into a pretty good all-American accent.

It must be particularly aggravating, considering how hard he has worked just to get his foot in the door. “I still have to prove why I need to get paid,” he agrees. “They always come at me with a complete low ball: ‘We only have this much for the role, but we love you so much and we really think you can bring so much.’”

“Viola Davis said it beautifully: she’s won an Oscar, she’s won an Emmy, she’s won a Tony and she still can’t get paid. [She added a Grammy in February.] Film after film, it’s a struggle. I have yet to meet the film that paid me fairly.”

But there are positives on the horizon. He is crossing his fingers for a part in the Gladiator sequel, while he was given far more screen time in the Shazam! sequel – in the kind of comedic role he has rarely been given. “Out of them all, the DC universe has a level of respect,” he says. “There wasn’t much to the role at first and I did it and it was fun. But the second time around it was a little more respectful.”

Finally, Hollywood is starting to value him. “From time to time, they themselves make the point of saying: ‘We should give him more, he’s a little underappreciated.’ I think they recognise that themselves,” he says, before brushing it off. “Hey, it’s the struggle I have to overcome!” Considering what Hounsou has already overcome, you would be foolish to bet against him.