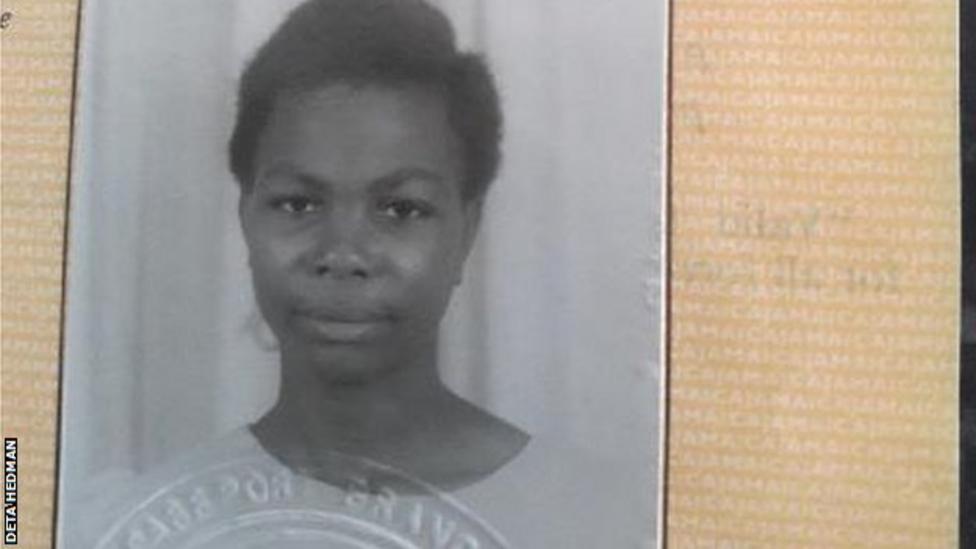

It all started in the house at the top of the hill. The highest of five homes on a road in Castleton, Jamaica is where the darts journey began for Deta Hedman. A journey that established her as one of Britain’s most successful female darts players.

When asked how she first got into the sport Hedman lets out a low, easy laugh. She is 60 years old and it was quite a while ago, you know.

It’s the laugh of someone who has earned the right to playfully mock younger journalists trying to pry into the past.

But there is a reason Hedman is sharing her story now. A BBC Sport survey found that one in five elite British sportswomen had experienced or witnessed racism and almost a third had been trolled on social media.

Hedman is one of the faces behind those statistics.

Making her way up in a predominantly white sport as a black immigrant in 1970s England came with untold hardships.

And the abuse hasn’t gone away.

When Deta Hedman was two years old, her father left Jamaica and her mother followed shortly after. She did not see them again until she was 13.

The experience wasn’t uncommon at the time.

Like many other members of the Windrush generation, Hedman’s parents travelled to England in search of work and a better life for their children.

Hedman and her five siblings were left behind, moving from house to house between family members until they eventually settled with their maternal aunt in the house on the top of the hill.

She describes Castleton as “not even a village, more a collection of houses jotted about” and has no trouble remembering the place where she lived.

The house was made of wood with a zinc roof and a veranda. In the evenings, a paraffin lamp and candles were the only source of light.

When she was there, every day began at the creek.

With no running water or electricity in Castleton, Deta Hedman would walk a mile with a bucket, back and forth until she had enough water for the whole family to drink.

Every week would follow a similar pattern. From Monday to Thursday she went to school, travelling to the creek before or after lessons to collect water or wash clothes.

Fridays were spent at the farm. The whole family would set out at 3am on the long journey with their horse, mule and donkey to collect produce for her aunt to sell at the market on Saturdays.

On Sundays, a lorry laden with blocks of ice would arrive in Castleton. Deta Hedman and her siblings would await its arrival and rush home to bury their treasure before it melted – a makeshift fridge in the ground.

“It was hard in Jamaica, that’s all I can say,” Hedman recalls.

“We were a poor family. You got the education – you could learn to read and write. The rest of it was just surviving the best we could.

“As kids you didn’t think any different because that’s what your life was so you just get on with it. You adjusted to what you had.”

That would become something of a mantra for Hedman – “just get on with it”. Sometimes, it was all she could do.

When Hedman’s parents first arrived in England they struggled to find somewhere to live.

Many landlords would not rent to a black couple and when they found one that would, prices were high.

But they established a home in Witham, Essex and gradually began to bring their children over when they could afford to.

The beginning of her English childhood came as a shock to Deta Hedman, who along with two of her brothers was the last of the family to move in 1973.

She had never owned a coat but soon became convinced of the necessity as she stepped off the plane into the bitter cold of a British January.

The memory brings forth another warming laugh. “When I arrived I remember I had this little dress on. Oh my god I was so cold,” she says.

“Where we were it was warm all the time. Our winter was like English summer.

“Because I came from Jamaica where it was predominantly black people, when I did arrive and saw all the different colours and different hair, I found myself staring.

“I remember when I saw my first snow, I went out in it and picked it up. It was ice. Ice was a luxury for us in Jamaica.”

Deta Hedman arrived speaking Jamaican patois and she would often have to help translate what her brother was saying for teachers at school.

She says her exams “went by the by” as she struggled to make the transition from a Jamaican education to an English one.

But it was what she had been doing after school that would come to determine the course of her life.

Hedman’s older brother had come to England years before her and was married with children by the time she arrived.

She used to babysit for him and when he got home from his night out, they would play darts. As younger sisters often do, Hedman refused to leave until she could claim some victory. At first, she just wanted to win a leg.

“I just think he let me win a leg so I could go home,” she jokes.

Once she was old enough, or – she admits – tall enough to pass for 18, she went to the pub and played there.

Sunday afternoons once spent waiting for the ice lorry in Castleton were now passed at The Crown in Witham. Hedman would put her name on the chalkboard and wait her turn.

“Those were the days,” she says. “They were good times.”

Deta Hedman, her two brothers and a friend would travel around Essex playing at different pubs. She says they were the only black people who did so at the time.

According to Hedman, they did not encounter discrimination locally because of the number of black families living in Witham.

“The racism really came once I ventured out into the world of competitions,” she says.

In 1984, a 25-year-old Deta Hedman was invited to join a super league, which involved travelling more to compete, and then got picked to play for the county.

During the week she worked fitting kitchens and on the weekends she and other players got in the car and went wherever the competition was.

It was exciting – first Ilford and Romford in east London, then further afield to Norfolk or Hampshire.

She met new faces, but even in friendship encountered ignorance. It did not always provide a safe haven from discrimination.

“I used to be called ‘the 6ft Mars bar’,” she says. “They all thought it was fun but inside it used to grind on me.

“There were a few times I used to say to people that I didn’t really like being called that.

“They would stop it but then somebody else would say it and you would just think, ‘what the hell. If it makes them happy let them get on with it’.

“At the time what could you have done?” she continues. “Not a lot really. You just take it on the chin.

“I used to just play my darts and let my darts do the talking.”

In 1987, at the age of 28, Hedman began playing in British Darts Organisation events – national tournaments organised for semi-professional players.

In 1990, she reached the Women’s World Masters final for the first time. Four years later, she won the competition.

She won another major, the Finder Masters, in 1996 and reigned as women’s world number one for three years between 1994 and 1997.

But by then, she had taken enough.

Having just started a new job at Royal Mail, Hedman said she was quitting darts because of work commitments.

She admits now that exhaustion from the racist abuse she received in the sport played its part too.

Her friends persuaded her to return and after five years she began to compete again. Not, she points out, because she was giving in to her friends’ demands. In fact, she had had enough of making decisions based on how other people viewed her.

Deta Hedman has fought to overcome a feeling that has held back too many women in history. She is not here to please.

“Sometimes you just think, ‘oh for God’s sake’,” she says. “I thought to myself why should I give up?

“It’s something I enjoy. If you don’t like me then that’s your problem. I’m not here to please you. I’m here to play a game that I enjoy. I won’t be pushed out by someone. I just tried not to let them grind me down.”

Hedman’s fire is inspiring and it could mislead you into thinking she has solved all her problems.

But of course she has not, because they are society’s problems and they are far from solved.

She took another break from darts in 2007 and when she returned in 2010, it seemed nothing had changed.

At events in the Isle of Man and Prague, spectators made blatantly racist comments about her. She heard the first one and her partner the second.

“You think: ‘Really? In this day and age?'” Hedman says.

“I just take it in my stride, if they say it in front of me I confront them. If I hear somebody say something and I don’t know who it is I can’t do anything about it.”

Forty-six years after taking up the sport, Hedman is still captain of the England Ladies team.

Having been runner-up three times in 2012, 2014 and 2016, she continues to chase a BDO World Championship title and is working to bring the next generation through as an ambassador for England Youth Darts.

The abuse continues.

After losing a World Championship match in 2019, Hedman was targeted via email and on Facebook. She was racially abused and was told by one person that they hoped she died of cancer.

But Hedman won’t be stopping.

“I am a fighter,” she says. “I don’t give up.

“If I like something and I want to do something, I will climb mountains to do it. When I get there and I’ve achieved it then I’ve done it so it’s basically: in your face.

“That’s my mentality and if somebody tries to put me down I will not sit down until I get the better of them.

“That’s what drives me.”