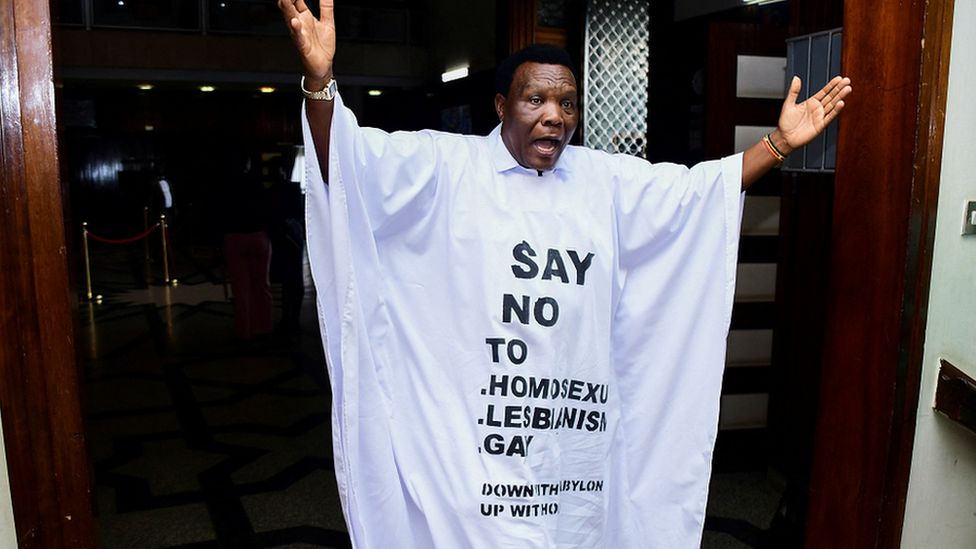

Uganda’s parliament last week passed one of the world’s toughest laws against homosexual activities, prompting widespread condemnation. If signed into law by the president, anyone who identifies as LGBT could face life in prison.

It also threatens the existence of the handful of refuges where LGBT people have sought shelter after being kicked out of home. The BBC got access to these secret shelters and spoke to residents about their lives and concerns.

Ali had kept his sexuality secret but was outed after he was arrested when Ugandan police raided an underground gay bar in the capital, Kampala, in 2019.

“My father said: ‘I never want to see you again. You’re not my child. I can’t have a child like you,’ says Ali, whose name has been changed to protect his identity.

Despite the obvious trauma of this experience the young man, in his mid-20s, speaks in a gentle, calm way.

“He was searching for me to beat me but my mother told me to hide. I did not have a plan, but I knew I had to leave home.”

His story of stigmatisation, violence and fear provides a glimpse into the lives of LGBT people in Uganda.

Gay sex is already outlawed in the country, but the new Anti-Homosexuality Bill goes even further.

The measure, still awaiting presidential assent before it becomes law, prescribes life in prison for anyone identifying as a sexual minority, as well as the death penalty for child sexual abuse committed by homosexuals. Raping a child under 14, or if the offender is HIV-positive, already carries the death penalty but this is rarely carried out.

It may also result in the closure of any shelter where people have gone to seek safety, as it defines as an offence anyone who leases a property “for the purpose of undertaking activities that encourage homosexuality”. They also could be interpreted as a brothel.

After fleeing his home four years ago, Ali was told about a place where he could live in relative safety that also provided meals and made efforts to find jobs for homeless gay men.

The former restaurant worker had only been there for a few months when the coronavirus lockdown began.

“In 2020, the shelter was raided by the police. We were lined up and the public called to stare at us, mock and humiliate us. People were spitting on us,” Ali tells the BBC.

He and over 20 other men were arrested, charged in court for violating pandemic restrictions on gatherings, and sent to prison.

“When we arrived in prison, some of the inmates already knew our story. They had read about it in the newspapers. We had to deny that we were homosexual to stay safe,” he explains.

His sociable demeanour belies the trauma he says he suffered while incarcerated.

“A warden who had seen the details of our case file ordered other inmates to beat us. He joined in too. Some of my friends were burnt in their private parts with firewood coals. We were beaten for about three hours, with wires and planks of wood,” he says, displaying the scars on his arms.

Uganda Prisons Service spokesperson Frank Baine denies that the men were assaulted while in detention. “When they were there, they were not known as gay [men]. Nobody tortured them and according to the officer in charge, there were no torture marks. They went on remand until they were bailed out,” he tells the BBC.

The government later dropped the charges against the group, and they were released after 50 days. Ali moved into yet another shelter.

Over 20 such homes exist across Uganda, operating with varying levels of secrecy.

“We normally have about 10 to 15 people in a shelter at any time,” says John Grace, the coordinator at the Uganda Minority Shelters Consortium.

Many LGBT people find safety and a sense of belonging in these temporary homes. But even here, danger is never far away.

Ali describes how he was attacked one evening in November last year.

“A group of young men started following me and shouting: ‘You gays, we are going to kill you.’ I did not respond and kept walking. One of them hit me on the head from behind.

“When I regained consciousness, I was in hospital and had bruises all over my face and a big wound on the back of my head.”

I was taken to the shelter, which he has called home for the past three years, through back roads to a neighbourhood in the north of Kampala. The residents are cautious about revealing the location.

There is a forlornness to the bungalow, which the owner seems to have set up initially as a family home, with its paint chipping in several places. It stands in a gated compound shaded by giant mango and jackfruit trees, beneath which clothes hang on a line to dry.

Aside from the kitchen which is overflowing with dishes, nearly every other inch of space on the inside, including the garage, has been converted into bedrooms. In what should be the living room, housemates lie or sit among mattresses, bedding, mosquito nets and half-packed bags with personal effects strewn all over the floor.

The sense of chaos is a direct result of the possibility of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill becoming law.

“After the bill was passed, the landlord told us to move. The manager of the shelter has said that we should have everything ready for when he finds a new house,” Ali tells the BBC, standing among disassembled triple-decker bunk beds.

But prospects are not good.

“In the event that the current shelter occupants are kicked out by the landlord, we do not have any viable options,” admits John Grace from the shelters’ umbrella group.

Furthermore, the future of the organisation is under threat.

“If the bill is signed by the president, we could face legal persecution, violence, discrimination and stigma for availing safe housing to homeless sexual minorities as well as identifying as sexual minorities ourselves,” John Grace adds.

Among the other house occupants is Tim – not their real name – whose parents stopped paying for university tuition after they were outed. Their father, a pastor, completely cut them off.

Tim recalls the lowest point.

“I did sex work, sleeping with different men just to have something to eat. Some nights I felt disgusted with myself. I would go to the shower and scrub myself like 10 times.

“I saw no future for myself – I had lost my family, lost an education, lost a sense of direction.”

Tim became a victim of cyber harassment on the day the Anti-Homosexuality Bill was debated in parliament.

“People were sending me messages, saying: ‘See what is going to happen to you?'”

“Some of us were beginning to recover a bit of our mental health. Now it scares me that a place like this could be tagged as a brothel. I feel like we had a wound that was beginning to heal and now it has been scratched open,” Tim tells the BBC, looking crestfallen.

“I doubt that we can regain any sense of dignity now because of the hate that has been piled on us.”

Uganda is already among 32 African countries that criminalise same-sex consensual sex between adults.

The bill has been widely condemned internationally, with the US saying it might consider sanctions against the country, and the European Union stating that it is against the death penalty in all circumstances.

Local and international activist groups have also joined the outcry.

When asked what he plans to do if the shelter is unable to find a place to relocate to, Ali’s voice cracks and he hangs his head.

“The only thought on my mind is: ‘Where will I go?'”

“Everyone is saying we are not normal, that we are not human beings. But this is what I am. I have contemplated going back home, but my father would never let me back into his house,” he says.

To find some grounding, Ali holds onto his Muslim faith.

“I know God is the one who created me and he knows why I am gay. So I continue to pray. Even now [during Ramadan] I am fasting,” he says.