The sister of a 16-year-old boy who drowned while swimming naked at a Christian holiday camp in Zimbabwe run by child abuser John Smyth blames the Church of England for his death.

“The Church knew about the abuses that John Smyth was doing. They should have stopped him. Had they stopped him, I think my brother [Guide Nyachuru] would still be alive,” Edith Nyachuru told the BBC.

The British barrister had moved to Zimbabwe with his wife and four children from Winchester in England in 1984 to work with an evangelistic organisation.

This was two years after an investigation revealed he had subjected boys in the UK, many of whom he had met at Christian holiday camps run by a charity he chaired that was linked to the Church, to traumatic physical, psychological and sexual abuse.

The 1982 report, prepared by Anglican clergyman Mark Ruston, about the canings said “the scale and severity of the practice was horrific”, with accounts of boys beaten so badly they bled, with one describing how he needed to wear nappies until his wounds scabbed over.

Despite these shocking revelations, mainly involving boys from elite British public schools, the Ruston report was not widely circulated.

A decade on, aged 50, Smyth had established himself as a respected member of the Christian community in Zimbabwe. He had set up his own organisation, Zambesi Ministries, with funding from the UK – and was meting out similar punishments at camps that he marketed at the country’s top schools.

Ms Nyachuru says her brother’s trip had been an early Christmas present from one of his other sisters, who had picked up one of Smyth’s brochures and been impressed with all the activities on offer for the week.

As she looks at an old photograph of Guide, she says he was the youngest of seven siblings, and the only boy: “He was very loved by everyone.

“A lovely boy… Guide was due to be made head boy the following year,” she remembers, adding that he was “an intelligent boy, a good swimmer, strong, healthy with no known medical conditions”.

But within 12 hours of him being dropped at the camp at Ruzawi School in Marondera, 74km (46 miles) from the capital, Harare, on the evening of 15 December 1992, the family received a call to say he had died.

Witnesses say that like all the boys, Guide had gone swimming naked in a pool before bed – a camp tradition. The other boys returned to the dormitory, but Guide’s absence was not noticed – which his sister finds surprising – and his body was found at the bottom of the pool the next morning.

His family rushed to the mortuary but Ms Nyachuru’s shock was compounded by confusion when she was stopped by officers from viewing his body: “They told me: ‘You can’t go in there because he is indecently dressed.’

“It was only my father, my brother-in-law and our pastor who went in and put him in the coffin.”

Nakedness appears to be something Smyth was fixated on at his camps. Camp attendees have told of how he would often parade around without clothes in the boys’ dormitories – where he also slept, unlike other staff members.

He would also shower naked with them in the communal showers and the boys were ordered not to wear underpants in bed.

“He promoted nakedness and encouraged the boys to walk around naked at the summer camp,” a former student who attended a camp at Ruzawi in 1991 told the BBC.

But his jocular manner put many of them at ease, he said.

“Smyth was very friendly, laid-back, approachable, he was really fun, always joking.

“Smyth would also walk the dorms and shower area wearing nothing but a towel slung over his shoulder.”

The reason given for the no-underwear-in-the-evening rule was “because it would make them grow”, he recalled.

Smyth gave talks on masturbation, would sometimes lead prayers in the nude and encouraged naked trampolining, an activity he described as “flappy jumping” – all behaviour noted in an investigation by Zimbabwean lawyer David Coltart that was launched in May 1993.

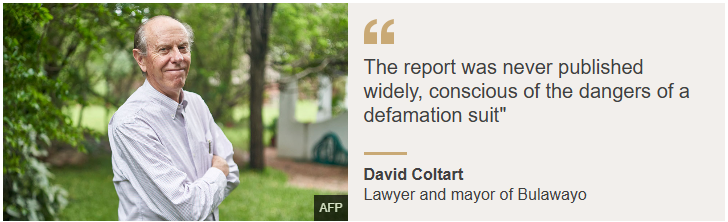

It was the thrashings that Smyth was giving boys with a notorious table tennis bat, dubbed “TTB”, that led a parent to the door of Coltart, who worked at a law practice in Zimbabwe’s second city, Bulawayo.

She wanted to know why one of her sons had returned from a holiday camp with bruises on his buttocks so severe that she took him to a doctor, who found a “12cm x 12cm bruise”.

“She saw these and demanded to know what happened and then it came out that her son had been badly beaten in the nude, and she came to me for advice,” Coltart, now mayor of Bulawayo, told the BBC.

“When I heard that this was a Christian organisation – I’m an elder in the Presbyterian Church – I got hold of my pastor and we got hold of the Baptist Church, Methodist Church and two other churches in the city and then I was instructed by those churches to investigate the matter,” he said.

Forty-four-year-old Jason Leanders, who went on the camp that immediately followed Guide’s death, said he was beaten three to four times a day by Smyth, who would put his hands into his pants to check he had not put on extra layers to cushion his buttocks.

“My bum was black,” he told the BBC. “But being a boy, you act tough.”

For many boarding school students, corporal punishment was regarded as “normal”, former Zimbabwean cricketer Henry Olonga, who was attending the camp the night Guide died, said in his 2015 autobiography.

But after Coltart managed to track down the Ruston report, the severity of the problem became apparent. He wrote to Smyth instructing him to immediately stop the Zambesi Ministries camps.

“It was calculated, he focused on boys. He groomed young men. He encouraged them to take showers in the nude with him. There was a pattern of violence,” he said.

But Coltart’s dealings with Smyth proved difficult.

“He was a highly articulate man and quite aggressive in the meetings that I had with him. He employed all his skills as a barrister to seek to intimidate. He was older than me. I was then a relatively young lawyer in my 30s. He exploited the fact that he was an English QC [Queen’s Counsel].”

Rather than comply with Coltart’s various requests, he doubled down and in a letter to parents ahead of the August 1993 camps, described himself as “a father figure to the camp” and defended the nudity and corporal punishment, writing: “I never cane the boys, but I do whack with a table tennis bat when necessary… although most regard TTB (as it is affectionately known) as little more than a joke.”

This time there appears to have been no cloaking of the beatings as “spiritual discipline” as had been the case in the UK. He also admitted to Coltart that he took photographs of naked boys, but said they were “from shoulders up” for publicity purposes.

Coltart contacted two psychologists with his findings, both of whom advised that Smyth should stop working with children.

His 21-page report was then published in October 1993, and circulated to head teachers and church leaders in Zimbabwe.

“The report was never published widely, conscious of the dangers of a defamation suit,” Coltart said.

However it “basically stopped him in his tracks in Zimbabwe” as the private schools were his harvesting ground, he said. Zambesi Ministries camps did continue in some guise, but not at schools or under Smyth’s leadership

Coltart then instructed another law firm to pursue a legal case against Smyth who was eventually charged with culpable homicide over Guide’s death, as well as charges relating to the beatings.

But, according to former BBC TV producer Andrew Graystone in his 2021 book about the abuse, the case was bedevilled with problems, police documents were missing and Smyth’s legal prowess led to the prosecutor being removed – another one was never appointed, so the case was essentially shelved in 1997.

Ms Nyachuru says no post-mortem was carried out at the time – Guide was buried on the day he drowned in the family’s home village, with Smyth presiding over the funeral.

Following the Coltart report, Smyth faced deportation from Zimbabwe but Graystone says he used his significant connections to avoid this, lobbying various cabinet ministers – some of whose sons had attended his camps – with suggestions that even then-President Robert Mugabe was approached by one of Smyth’s associates.

But from the time of Smyth’s prosecution, the family were given temporary residency permits, which had to be renewed every 30 days.

In 2001, having spent too long out of the country on a trip, Smyth and his wife Anne were refused re-entry, prompting their move to South Africa’s coastal city of Durban and then a few years later to Cape Town, where the couple were living when the Church of England became fully aware in 2013 of the abuses he had committed in the UK.

“The Anglican church in Cape Town in which John Smyth worshipped… has reported that it never received any reports suggesting he abused or groomed young people,” Thabo Makgoba, the archbishop of Cape Town, said in statement responding to this week’s resignation of Justin Welby as Archbishop of Canterbury.

Smyth was only excommunicated by his local church the year before his death in 2018, after he was named publicly as an abuser in a Channel 4 News report.

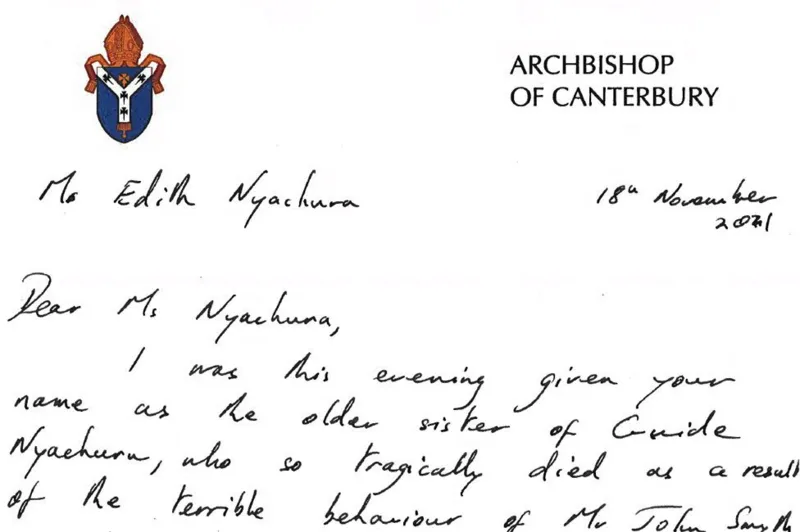

Ms Nyachuru told the BBC it was not until 2021 that she received a written apology from Welby about the death of her brother, in which he admitted that Smyth was responsible and the church had failed her family.

She wrote back describing the apology as “too little, too late” and is now calling for other senior church leaders who failed to intervene to prevent Smyth’s abuse to resign: “I just think people of the church, if they see something not going in the right direction, if it needs the police they should go to the police.”

Coltart feels it is not just the Church that is to blame, and suggests other institutions in the UK need to face up to their failure to warn people in Zimbabwe.

He commended the Church of England’s recent Makin report, saying it “left no stone unturned”. The report estimates that around “85 boys and young men were physically abused in African countries, including Zimbabwe”.

Coltart urged the Church to reach out to them.

“I think possibly there are still victims in Zimbabwe, perhaps in South Africa, who are suffering from PTSD and I think the Anglican church has a responsibility to identify those individuals and to supply them with the medical assistance that they might require,” he said.

Mr Leanders says many of his friends are still “so traumatised by the beatings they are not even prepared to talk about it”.

“Smyth was protected in England and he was protected in Zimbabwe. The protection went on for so long it robbed victims the chance to confront Smyth as adults.”

Additional reporting from the BBC’s Gabriela Pomeroy.