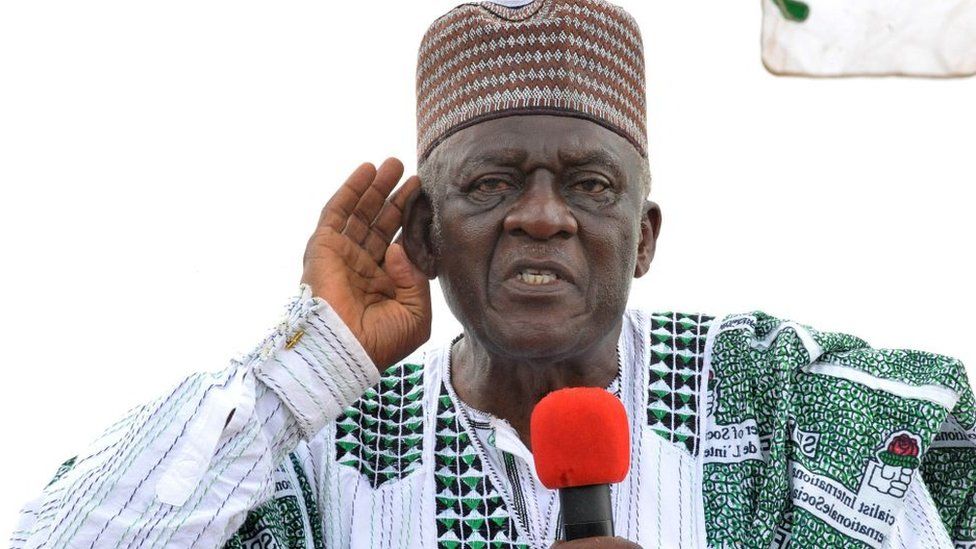

John Fru Ndi, the man regarded as Cameroon’s champion of democracy, has died at the age of 81.

He became a hero to many in the 1990s for his bravery at taking on the one-party state that brutally dealt with those challenging its rule.

A former bookseller and a great orator from the English-speaking area of Cameroon, he founded the opposition Social Democratic Front (SDF) in 1990.

His popularity led the regime to accept a multi-party system was inevitable.

In fact his party believed he won the 1992 presidential election, but the Supreme Court judge that heard its petition alleging fraud said his “hands were tied” – and let the official results granting victory to incumbent Paul Biya, with 40% of the vote, stand.

This caused great upset with SDF supporters and their leader was put under house arrest for three months in his home in the economic hub, Bamenda, and a state of emergency was declared.

Still the US must have given credence to his claim to the presidency, inviting him and his wife to the inauguration of Bill Clinton in January 1993.

Fru Ndi was not a supporter of the secessionist rebellion in Anglophone Cameroon that has claimed tens of thousands of lives over the last six years – and was even kidnapped and beaten up by militants in 2019, and part of his house was burnt down.

They were angered by what they saw as his betrayal for not supporting their demand for an independent state of Ambazonia, as they call Cameroon’s two English-speaking areas – the North-West and South-West regions.

Fru Ndi, popularly known as “The Chairman” after he launched the SDF, while always campaigning for the rights of English-speaking minority who felt marginalised by the country’s French-speaking majority, wanted a federal, unified Cameroon.

He favoured economic tactics, known as “ghost towns”, when huge swathes of the country would effectively go on strike, or street protests to make his case to the authorities.

His campaign rallies were always big events – pulling huge crowds across the country, not just in Anglophone areas.

They were regarded as great entertainment and a rare opportunity to hear someone seeming to speak truth to power.

A man of the people, he knew his audience and tended to speak in Pidgin English. They loved his jokes and gutsy performances, saying the SDF actually meant “Suffer Don Finish” in Pidgin, reflecting that under his leadership suffering would end.

He would raise his fist to shout “SDF” to the crowd, who would chant back en masse: “Power to the people!” This call and response was repeated until the third time when they would roar back: “Power to the people and equal opportunities!”

Goalkeeper and vendor

Fru Ndi was born in the village of Baba II, near Bamenda, in 1941, when the area was administered by British colonialists.

As a child he had ambitions to be a pilot and his family decided to send him to Nigeria to stay with relatives to finish his schooling aged about 16.

But he played truant from his studies, ending up making a living by doing odd jobs, only returning to Cameroon several years after independence in 1961, when the former British and French parts of Cameroon had unified.

His family felt, with Nigeria’s political upheavals, he was better off back home, fearing he might want to become involved in the civil war that had broken out there.

Starting off as a small-time street vendor, he became a successful businessman, setting up the Ebibi Bookshops, with branches in Bamenda and Mamfe.

He also made a name for himself on the football pitch, becoming goalkeeper for PWD Bamenda FC.

His self-made bookselling empire – the place to go for all school textbooks as well as other titles – allowed him to purchase farms and become well known for his beef and water melons.

At this time he became involved in local politics, and a member of the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM) party.

But he grew frustrated with the one-party system, and inspired by university lecturers and other activists who whispered about forming an opposition party – took their idea and had the courage to run with it.

When he launched the SDF, troops were deployed to Bamenda and opened fire on groups of his supporters, killing six people.

Yet he stood firm and loud in his defiance and the wind of multi-party change sweeping across Africa became a reality for President Biya, a southerner who had been in power since 1982.

The two men only met once despite their long years of political sparring.

Fru Ndi’s grassroots’ appeal and lack of a university education led some in the ruling party to mock him, referring to him as “The Bookseller”.

He had given up his book chain in the 1990s to concentrate on politics – and stood in other elections.

‘No regrets’

One of his great failings is, perhaps, after having managed at one time to unite other opposition parties into a coalition, he failed to get them to agree to field a single candidate to take on Mr Biya.

Over the last three decades Mr Biya has always been able to dominate because of the fractured opposition.

The SDF also accused the authorities of constant harassment, blocking roads to rallies and putting other obstacles in their way – and more recently using internet shutdowns.

Several months after losing the 2004 presidential election, Fru Ndi’s second wife Rose died. They had had several children together in a marriage that lasted more than 25 years – and after her death he also became involved in charity work, setting up a foundation in her name.

His first wife Susan had tragically died giving birth in 1973.

Latterly Fru Ndi was accused by some in the SDF of dominating the party, and squashing other voices.

There have been undignified court battles over high-profile expulsions from the party, but just before his death Fru Ndi said he would be stepping down as SDF chairman at a party conference scheduled for next month.

Over the last few years he had occasionally sought medical treatment abroad, coming back from his most recent trip 10 days ago.

He died at his home in the capital, Yaoundé, where he had had to relocate because of the insecurity in Bamenda – a great sadness to him.

But he said he had no real regrets, telling state TV recently: “I have lived a full life. I have done everything I wanted to do.”