The Somali militant group al-Shabab recruits thousands of foot soldiers, but also needs people to provide public services in the area it controls. Any caught trying to leave are put to death. At the same time, the government tries to encourage defectors, and runs rehab centres to help them re-enter society.

There are three of them sitting opposite me in the dark room.

Ibrahim is on the left. His gaze is confident, sunglasses tucked into his striped polo shirt, a large watch around his wrist and big brown eyes shining beneath his baseball cap. He says he is 35.

Moulid is in the middle. He is thin and wears yellow flip flops to match his yellow shirt. He is 28 years old.

On the right is Ahmed. He has a neat beard with a keffiyeh scarf wrapped around his head. He is wearing a sky-blue shirt with a sky blue T-shirt underneath. He is 40.

They have a complaint.

They do not like the breakfast on offer in this safe place, behind the wire at Mogadishu’s international airport.

“It is not our normal food, like pancakes and beans. We do not like bottled water. We like a simple life and simple water,” says Ahmed. Unfortunately, the airport caters to international tastes. There is pizza, steak and beer, not Somali fare.

I start to tell the three men that I will not use their real names, will not take their photos and will not report on anything that could get them into trouble or that they feel uncomfortable talking about.

Ibrahim interrupts me.

“We are not afraid to tell our stories. Ask us anything you want. You can take our photos and use our real names.”

However, I decide not to take their photos and not to use their real names because I fear for their lives.

This is because they have all defected from the violent Islamist group, al-Shabab, which has been in existence for more than a decade and controls large parts of Somalia, imposing harsh rules and punishments. The group has set up a parallel administration, with ministries, a police force and a justice system. It runs schools and health centres, irrigates land and repairs roads and bridges, and needs people to carry out this work.

The penalty for defecting is death. Al-Shabab has told me this penalty applies to anyone who leaves the group without permission, not just fighters.

“The only reason I joined al-Shabab was money,” says Ahmed, the straightest talker of the three. “They paid me from $200 to $300 a month. I was in charge of their transport system in my area.”

Ibrahim rubs the fingers of his right hand together in rapid movements to symbolise money.

“I too joined for cash. I was an al-Shabab foot soldier for three years. When you are in it you enjoy it.

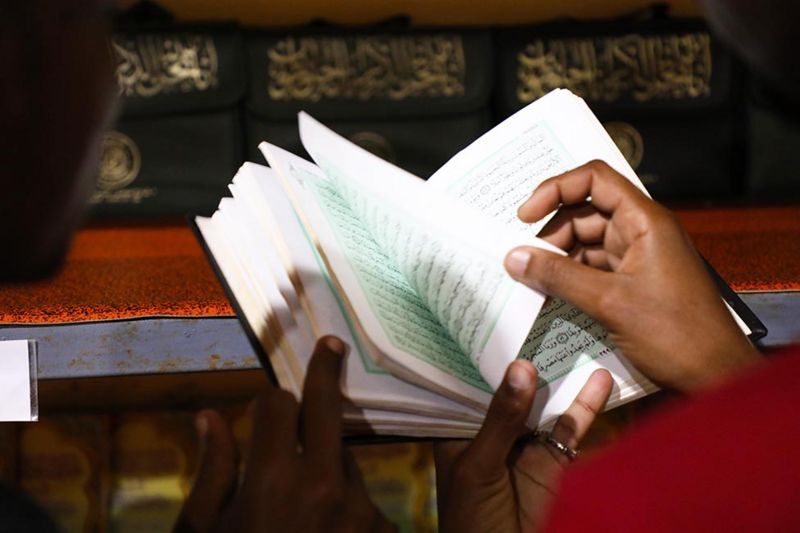

“The thing I did not enjoy about being in al-Shabab was the way they tried to alter my mind. Every two weeks they sent a brainwashing team to our battalion which sat with us for hours reciting verses from the Koran and repeating over and over again how the government, the African Union and its other international supporters were infidels and apostates.

“It was as if they inserted al-Shabab sim cards into our brains.”

The three men say that even though their minds were warped by this indoctrination, they came to realise that the group was not fighting for a purer, better form of Islam, but a twisted, misguided one. It was no longer enough that the militants paid them money.

But the decision to defect was terrifying, they tell me.

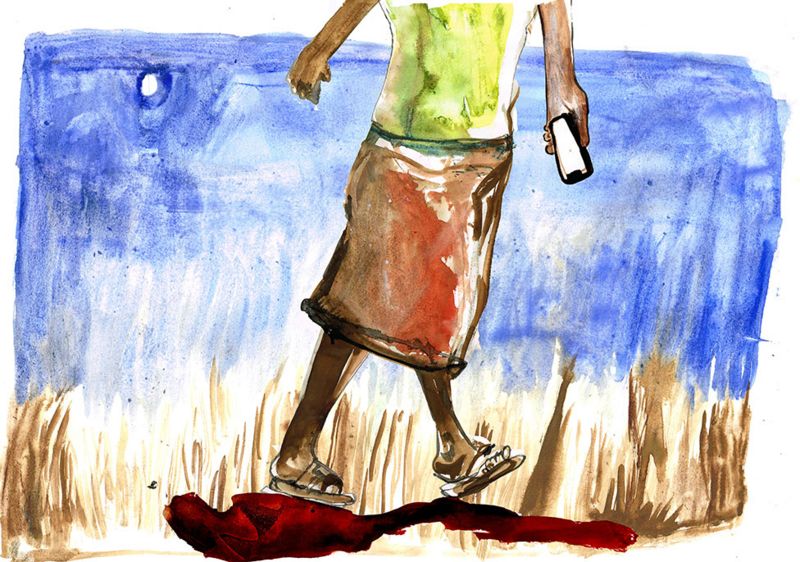

First there was the escape, then the long, lonely march out of al-Shabab territory.

“At the beginning I walked by night, my feet lacerated by thorns,” Ahmed says. “Luckily I had my phone, so I contacted my family. They found someone I could trust, who guided me to a safer place. It took days, and I was consumed with fear every step I took. I was petrified I would be stopped and sent back to certain death, by execution in a public place, as that is what al-Shabab does to defectors.”

But there is also the fear of what will happen on the other side, as senior militants tell recruits that defectors will be tortured with electric shocks by the Somali security services.

Most do not know there are government amnesty or rehabilitation centres where they will be “re-educated” and integrated back into society.

There are efforts to spread the word inside al-Shabab territory about this defectors’ programme. Colourful leaflets have been designed, with images for those who cannot read showing members of al-Shabab being rescued, and a phone number they can call. These efforts have led to an increase in defections, with more than 60 leaving al-Shabab in a two-month period earlier this year.

Ibrahim, who was in al-Shabab for three years, took two months to decide to leave. He says he will never return to his home village – he will spend the rest of life trying to melt into the big city of Mogadishu. Otherwise al-Shabab will find and execute him.

All three men ended up at a rehabilitation centre called Serendi in the capital, Mogadishu. So serious are the threats against them that when I visited, there were 80 guards for 84 defectors.

The centre does not take senior members of al-Shabab; there is a separate high-level defectors’ programme for the more dangerous masterminds of the group. Serendi is for low-ranking members – foot soldiers, porters, mechanics and the like.

Before they are admitted, the defectors are screened by the National Intelligence and Security Agency to make sure they have voluntarily disengaged from the group and denounced its ideology.

But a journalist in Mogadishu tells me that some active members of al-Shabab slip through the net and send messages to the group from within the camp.

The aim of Serendi is to rehabilitate the defectors physically, mentally and spiritually, and provide them with skills so they can slowly integrate into life outside, either back with their home communities or elsewhere.

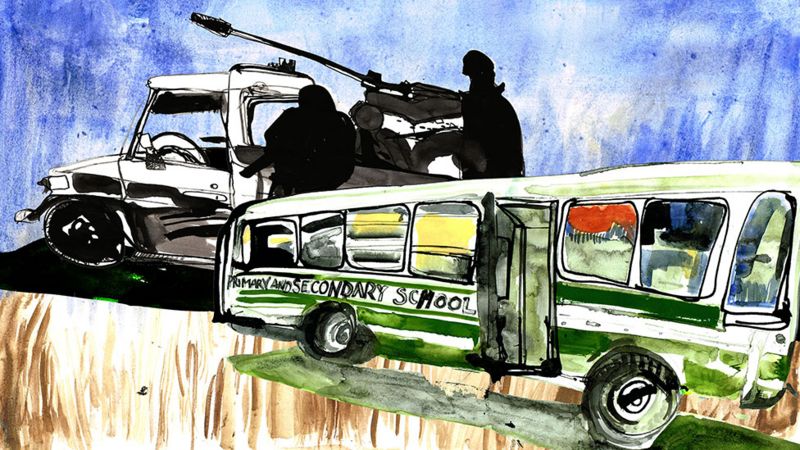

“I drove an armed pickup truck, which we called ‘Volvo’, when I was in al-Shabab. I was afraid of nothing,” says Moulid.

“When I got to Serendi, the supervisors saw I had a talent for driving. I worked as a driving instructor in the camp, teaching other defectors how to drive. Now I have a job as a school bus driver. One day I would like to set up my own transport business.”

Ahmed now makes money buying and selling land.

Ibrahim describes how he learned to be a barber in Serendi and soon demonstrated such flair that he started to earn money in the camp by cutting the hair of the other defectors and guards.

He now has a barber’s shop in Mogadishu, where he employs three people. “I earn enough to support my two wives and eight children,” he says, adding that he has brought them to the city to live with him.

But life after al-Shabab is rarely easy.

Moulid explains that some members of his family have rejected him, and that others do not trust him.

Ibrahim says he could not return to his community even if there wasn’t the danger of being hunted down and killed there. Although his family has forgiven him, his neighbours have not.

And he says that deep inside he still has wounds from his time in al-Shabab – that he is haunted by it.

“I am struggling to remove the al-Shabab sim card from my brain,” he says. “Images of the bad things I did, and the bad things that were done to me, flash before my eyes.”

Inside Serendi, the defectors crowd into classrooms where they study basic literacy, English, maths and other subjects. Others learn mechanics, welding, IT, driving and other skills.

In a large room, apprentice tailors sew colourful dresses which are displayed on mannequins on the wall. In al-Shabab territory women have to wear heavy gowns and hijabs, mainly black or another subdued colour.

After the outbreak of coronavirus, the tailors started to make protective face masks for distribution outside Serendi.

A few young men relax in their dormitory, the room lined with neatly arranged bunk beds. There are large, lockable storage boxes at the foot of each bed where they keep their possessions.

Loud music blasts out of another room. Two defectors are singing and dancing – activities completely forbidden by the militants, apart from the chanting of verses from the Koran – but they occasionally break into military step, similar to the marching style shown in al-Shabab recruitment videos. It’s as though they cannot shake off the past, as though they are still programmed to move in the way they had to under al-Shabab.

A professional football coach comes to Serendi where he brings together the defectors, staff and the guards to play games on a well-maintained pitch.

Sheikhs visit to help with deradicalisation, to convince the young men that there is another kind of Islam unlike that drilled into them by al-Shabab.

The centre’s staff explain how the defectors receive political education to make them more positive about the government.

After a period they are allowed to take weekend leave, while some study or work outside the centre, coming back to Serendi in the late afternoon.

There is a two-bed clinic where medical staff treat defectors for typhoid, malaria, malnutrition, hepatitis and parasites. They say syphilis is the most common disease among the new arrivals. Some come to the centre severely dehydrated, their bodies scarred by bullets, some of which remain within their bodies.

But Serendi has not always been the functioning, positive place it is today. It was founded in 2012 and struggled to find its way. At times, conditions were so bad that some residents actively discouraged their former comrades from leaving al-Shabab. (Militant leaders allow recruits to have phones, even though they sometimes take them away for part of the week.)

Now that Serendi is operating more successfully, rehabilitation centres are also being set up for defectors’ wives – who sometimes accompany their husbands when they are hired to work for al-Shabab – and for women who have been active in the group.

I meet a neatly dressed and softly spoken young man, Bashir, who recently left Serendi after two years there. It is difficult to imagine how such a gentle person could have been a member of a group that focuses so intently on violence, both in its actions and its words.

“I was a teenager when I joined. I was good at science. Al-Shabab said I could help in their medical team. I did not dare say no to them and I needed the money. They paid me $70 a month,” he says.

Bashir used the $250 he received when he left Serendi to enrol at university and set up a small pharmacy.

“I sell ice creams there as well,” he says. “I am scared every day that al-Shabab will hunt me down.”

This is a real possibility. Al-Shabab regularly assassinates people in Mogadishu; residents of the city say the militants are everywhere. They “tax” people, distribute charity and dispense justice in areas nominally under government control.

Despite its initial problems, the low-level defectors programme seems to be working for those who join. Serendi’s staff say hundreds of people have completed the programme, and they are unaware of any who have returned to al-Shabab.

Thousands more remain in al-Shabab and continue to strike terror in Somalia and beyond. The group has struck hotels and shopping malls in the heart of Kenya’s capital Nairobi. It carries out huge truck bombings in Mogadishu, killing hundreds at a time.

Ibrahim, Moulid, Ahmed and Bashir are all making lives for themselves and seem genuinely relieved to be free from al-Shabab. The challenge will be to convince many more to leave and make their way to centres like Serendi.