In the early years of the fight for freedom and ensuring the respect of human rights in Nigeria, there are some personalities the story can never be told without.

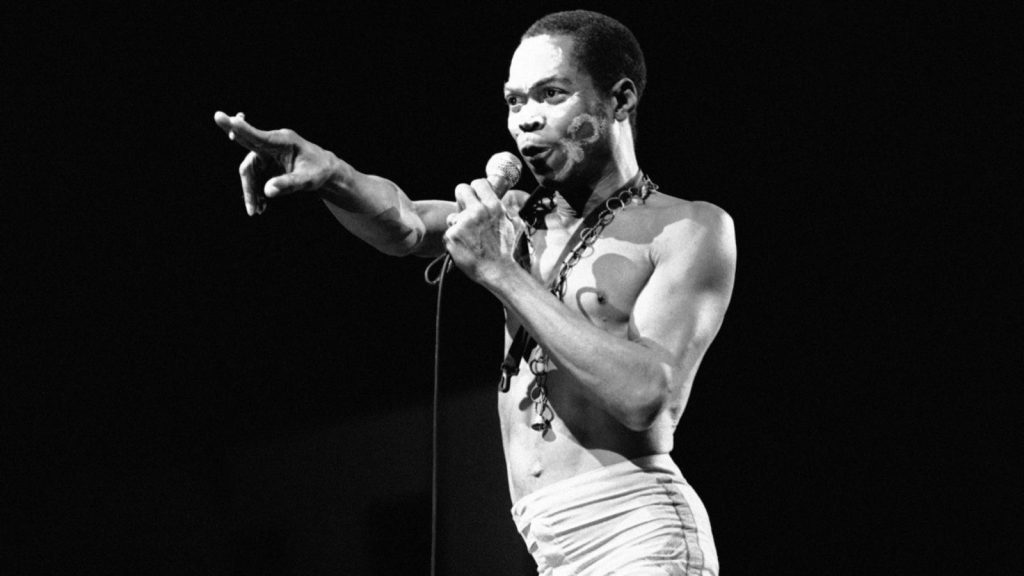

Fela Kuti and Wole Soyinka have gone down in history as some of the stubborn creatives who did everything to frustrate the military and corrupt governments and despite constant persecution, never gave up on their cause.

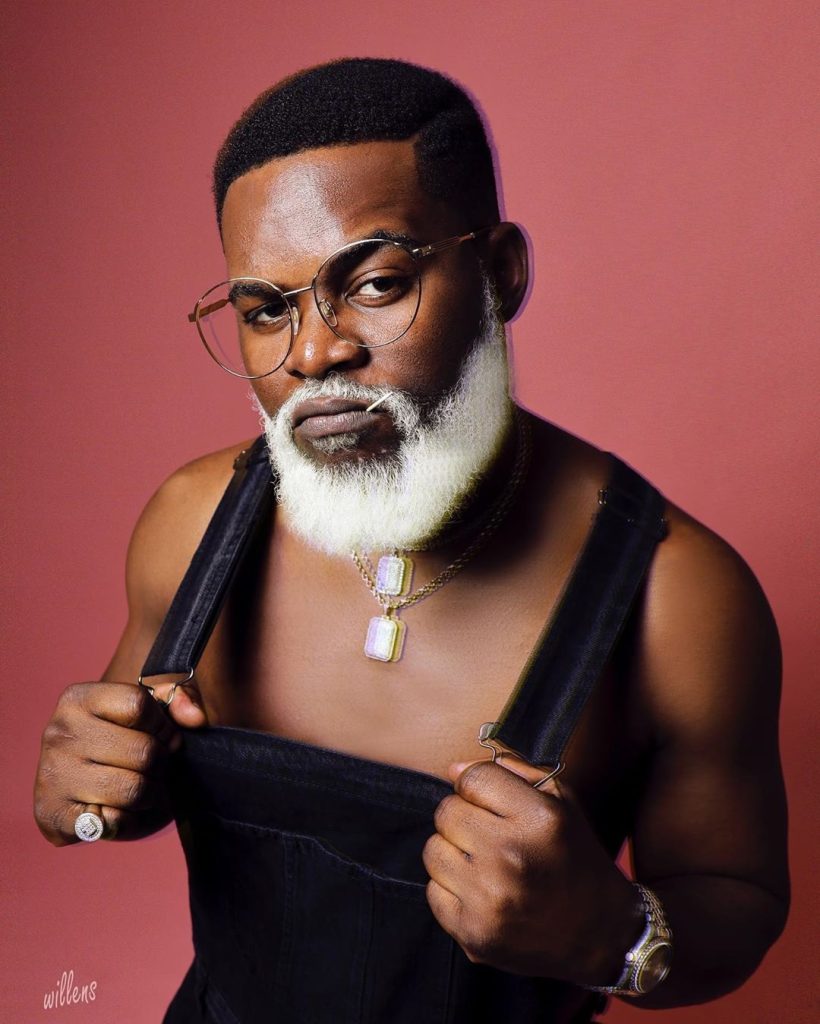

Femi Kuti, son of renowned music and 4-time Grammy-nominated artist, Fela Kuti, narrates his life growing up in the shadow of one of Nigeria’s most famous musicians, and how that has shaped his life and own musical career.

Fela Kuti had a place called the ‘Katakuta Republic’ and this was a small joint that could harbour as many as 150 people who partied virtually all day, all weekend.

‘The Katakuta was raided more times than we could count. They always had a different reason for showing up to raid the place. It gets closed for a few days and knowing Kuti, he had it up and running in no time,’ Femi recalled.

As the eldest child of his dad and also one who bore a striking resemblance to the legend, Femi Kuti was dragged into many of his father’s battles even when he would rather not want to.

Growing up, Femi was always engaged in one brawl or another in school, in his neighbourhood and everywhere else, because people always had really ugly things to say about his dad.

Fela Kuti always used his music to chastise the military government and vocally talk about everything they did wrong, including corruption. ‘I always had to fight people in school because they always had something cruel to say about my dad. Even later in life, when we had boyfriends and girlfriends, my siblings and I were sometimes sent out of their homes when their parents realised we were children of Fela.’

This bad treatment was not more than the family could handle. They had grown used to the constant military harassment and found it as a part of their lives, until in 1977 when Fela Kuti sang his song ‘Zombie’, literally hitting at the military and calling them robots with no minds of their own.

‘One day I was out playing in the field when some boys passed by and told me my dad’s house was being burnt to the ground. I thought it was the usual harassment, so I rained insults on them too and cursed them out.But, they insisted they were not kidding this time, and the house was indeed being burnt.’

Femi Kuti recalls running quickly back home, getting in a car with him mum and siblings and making it to the Kalakuta to ascertain the rumour. True to word, the military had surrounded his father’s home and had set it on fire.

Fela’s mum, Femi’s grandma, a human right’s activist in her own light was old and could barely make her way out of the burning building. The military found her in one of the upstairs bedrooms and threw her out the window.

The old lady did not survive this and eventually died. This only further infuriated Fela Kuti who decided to retaliate by carrying an empty coffin to Obasanjo, simply to register his displeasure. Of course, he would not go without his first son, Femi.

‘I pretended to be sleeping in my room when he sent for me to be called because it was time to deliver the coffin. I had been praying weeks un-end for him to forget to take me along, but guess that was not going to happen. I refused the first call, and then a second one came, I still pretended to be asleep. On the third call he only added a message saying, ‘if you don’t come down I will come to call you myself’ and in every African home, that meant danger.’

Femi Kuti respectfully followed his father with the coffin and of course, they were brutally beaten and sent out. Fela went on to sing his ‘Waka Waka’ song depicting this moment as well.

When the military had had just about enough, Fela Kuti was finally arrested and imprisoned for 20 months during which he never stopped his controversies. Whilst his father was in prison, Femi played with his father’s bad for a while and then decided to find his own path.

‘I did not want to stay in my father’s shadow forever. I love my father and I would have no one else as my dad, but I just wanted to do things my own way. My father was too radical in his dealings. I wanted to be more tactical and more careful. If I say I am not paranoid after everything I have seen growing up, that did be a lie. I am very paranoid and that is why I do my music and still send my message across but in a more tactical way,’ Femi Kuti explains.

In 1997, after 10 studio albums, 4 Grammy nominations, a ton of impact, frustrating the military, dragging Femi into his act and hoping Femi did be like him later in life, Fela Kuti died, living behind a legendary status no one has ever attempted to diminish.

Femi on the other end has his own ‘shrine’- The New Afrika Shrine – which mimics his father’s Republic from back in the day.

As life would have it, Fela Kuti’s cousin, just happened to be another forerunner in the history of Nigeria’s fight for the respect of human right and total freedom.

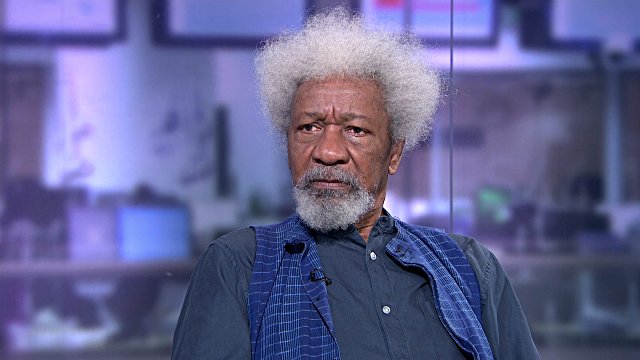

Africa’s first Nobel Laureate, poet, playwright and essayist Wole Soyinka was the next creative to share his story.

Barely 7 years after Nigeria had gained its independence, the country was slowly tilting towards the unimaginable. There was a silent war brewing, corruption was at it’s highest peak, human rights abuse was so rampant it felt normal and no-one and nothing seemed to work in the country.

The Biafrans in the South of the country were continuously being brutalised and wanted out of the country. Wole Soyinka did not think this was a very good idea. He wondered why a part of the country should be subjected to these inhuman forms of treatement.

‘I thought if I moved to Biafra and spoke to their leader myself, I may be able to be a bridge between them and the government. I was simply looking for a way to broker peace.’

When Wole Soyinka was finally ready to go to Biafra, that whole section of the county was blocked off and they allowed no-one inside. By virtue of his popularity through his political activism and articles, though Wole faced a lot of human blockades, he could calmly talk them into the reason why he was there and how they could help him.

Soyinka succeeded in speaking to the Biafran leader – General Ojuku- and he, in turn, gave Wole a least of demands to be delivered to the government. This was in 1967. Wole Soyinka made it back and he was immediately arrested for being a spy and belonging to the traitors as the Biafrans were called.

Wole Soyinka started his prison journey in Kirikiri. While in there, Soyinka was denied access to his tools (his pen and paper) and hence took to scribbling on the walls with pieces of sticks.

‘In there they try to completely take over your mind. They want you to completely lose it. I was in solitary most of the time since they could not have me influencing others with my ideologies. Instead of being frustrated by this treatment, I built a micro-world in there for myself. I learned how the ants got their food, how the soldier ants burrowed, I spent time fortifying the mind they desperately wanted to destroy. I will not say they still did not get to me, they did. There were days when I could hallucinate and feel I was loosing my mind.’

Wole with time gained the trust of his guards and wardens and was able to sneak in books and pens. He started communicating with the outside world and that was when he heard Neils Armstrong was making the journey to the moon. ‘I loved science and when I heard this news, I decided to follow him with my mind. So, yes! I made the journey to the moon with Armstrong.’

Through his communication with the outside world, Soyinka built a network for himself of people who kept him updated on all matters political and otherwise that happened in Nigeria. Even in prison, Soyinka used his poems and written pieces to inspire people. He would sneak out some of his poems and this would cause a lot of noise and range even though he was away in prison.

In 1969, Wole Soyinka was released from prison and heard the war had just come to an end, but without the shedding of many Biafran and civil lives. Wole was totally devastated by what had happened in his beloved country. This greatly affected his psyche and got him to go into voluntary exile away from Nigeria.

Since his first exile, Wole Soyinka kept coming in and out of Nigeria, always on the run from the government and still using his network and movement to speak up for the people of Nigeria.

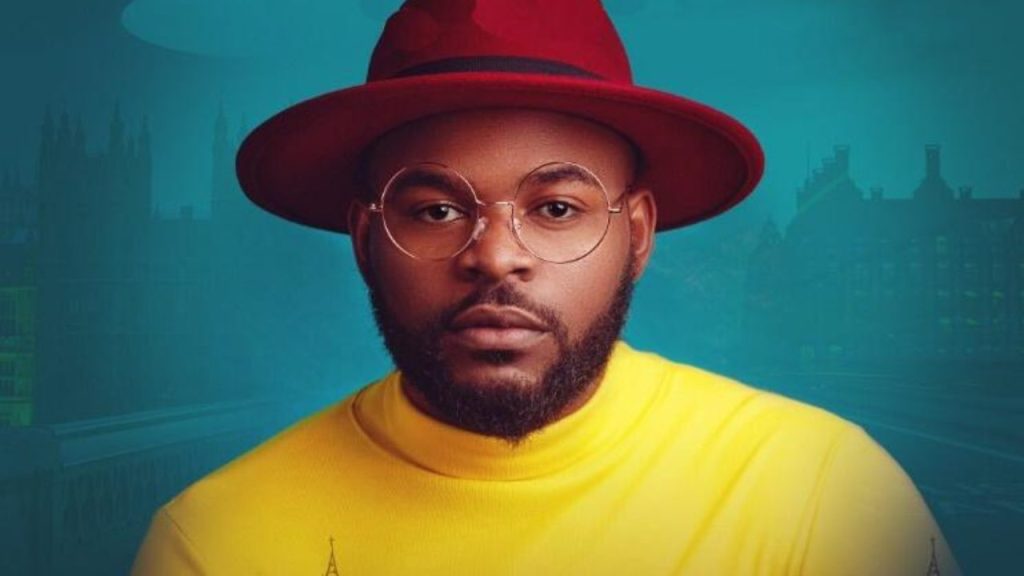

Rather of a new generation, but still seeking to continue what the others did, Nigerian rapper, Folarin Falana better known as Falz is the next to share his story.

Falz, a lawyer by profession is the son of Femi Falana (a lawyer who represented Fela Kuti and Wole Soyinka whenever they were arrested) and Funmi Falana, also a legal practitioner.

Growing up, Falz always saw his dad fight for the rights of people and saw him fight for people to be treated fairly. He remembers his father being arrested and taken away from home so many times, but he was too young to understand what was happening at the time.

‘I remember sometimes we don’t see my dad for a while and when you ask my mum she did simply say my dad travelled and he would get us sweets on his way back. At the time, we were kids and did not understand much, so this was enough reason for us,’ Falz recalled.

Through the work of his parents, Folarin Falana developed an interest in law and proceeded to study law at the university. Even whilst in school, Falz still pursued music but only as a passion.

After he was called to the bar, Folarin practised law at his father’s firm where he was as a lawyer by day and a rapper at night.

In two years, Falz was completely consumed by the desire to be a musician and hence quit his day job to focus fully on music. ‘I was becoming popular and I had started making money from music. It was my passion also, so I did not see why I should not pursue it fully.’

In 2018. Falz gained political attention when his song, ‘This is Nigeria’ – a cover of Childish Gambino’s “This Is America”- made waves all over the country. “This Is Nigeria” addresses a number of societal issues prevalent in Nigeria, including SARS brutality, codeine abuse, and unrestrained killings.

It went as far as being banned on radio because it was vulgar.

‘I am a lawyer. I know what words to use, so no one finds anything to hold on to. I searched the dictionary for the meaning of vulgar and it did not match the song in anyway.’

Falz’s song caught fire, becoming popular amongst people of all walks of life and of all ages and especially the political fraternity.

Knowing he is on their rada, Falz says he will continue to express himself through music because it is just another way to continue the legacy of his parents.

Falz is a part of the new rebel artists budding in Nigeria, in the hope of building a better and more inclusive society one day.