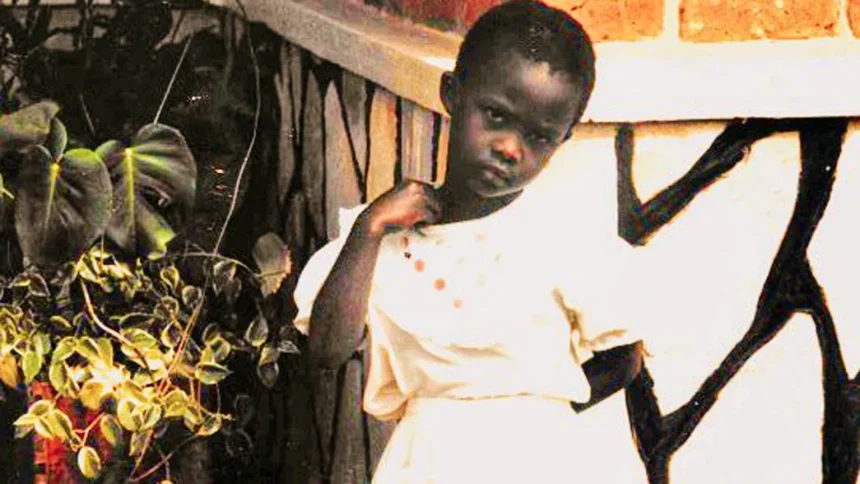

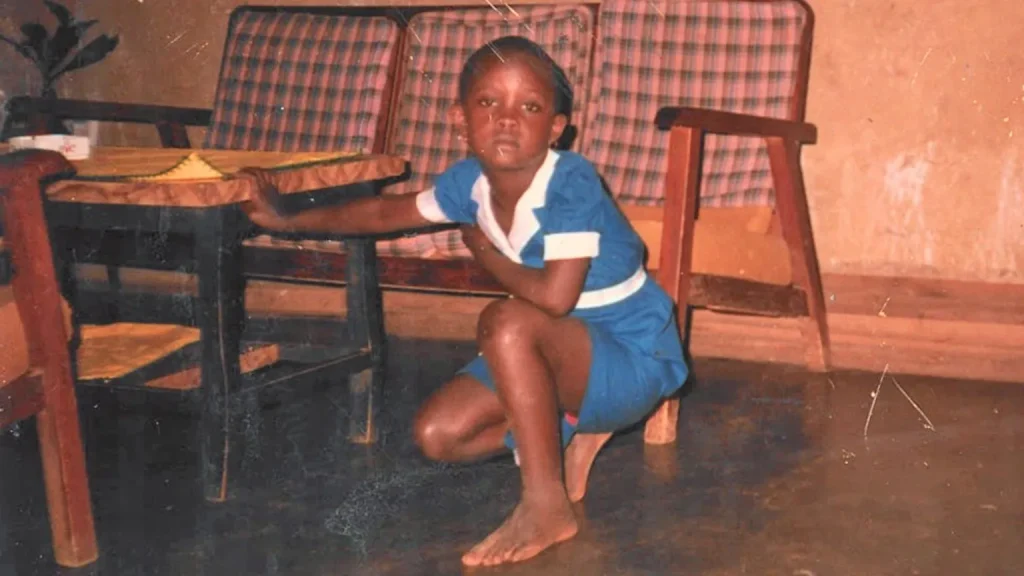

I left my home in Rwanda, the country of my birth, 30 years ago at the age of 12 – fleeing with my family from the horrors of the 1994 genocide.

Growing up in Kenya and Norway and then settling in London, I often wondered what it would be like to go back and see if and how the country and the people had healed.

When offered the opportunity to travel there to make a documentary on that very topic, I was excited but also extremely anxious about what I would find – and how I would react.

Warning: Some people may find details in this story distressing.

I have lived with the emotional scars of these events in the form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which can be triggered unexpectedly.

Like many Rwandans, I lost many family members. In just 100 days, 800,000 people were killed by ethnic Hutu extremists targeting members of the minority Tutsi community, as well as their political opponents, irrespective of their ethnic origin.

The mainly Tutsi forces who took power following the genocide were also alleged to have killed thousands of Hutu people in Rwanda in retaliation.

Emotions were swirling within me when I landed in the capital, Kigali.

The joy of hearing my language Kinyarwanda being spoken all around me. But also the recognition that the last time I was in the city, chaos reigned, with millions of us running for our lives, trying to stay alive.

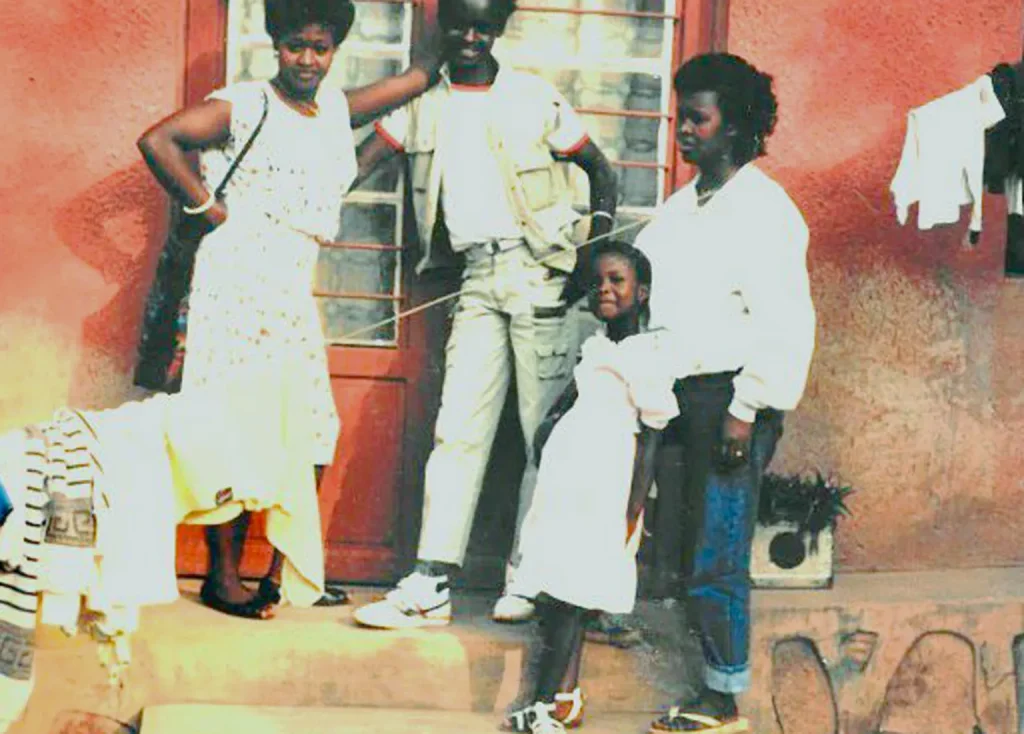

A few of the places I yearned to see during my short trip were my primary school and my last home in Kigali – where I was sitting at the dinner table with relatives on that fateful night of 6 April 1994. This is when we heard that the president’s plane had been shot down – a phone call that turned all our lives upside down.

But of all my worries, nothing could beat the sheer sadness that filled me when I could not find my family’s former house. After four attempts, I gave in and called my mum in Norway so she could guide me.

Finally standing in front of the closed gate, I choked up remembering the sunny warm afternoons we had sat on the terrace chatting and just being carefree.

It also forcefully brought back the turmoil of our leaving – being calmly told to put on three sets of clothes and bundled into the car for a journey none of us could have imagined.

I don’t remember any of us speaking or even complaining, despite us children being crammed tight together in the back – and even when hunger hit like I had never known.

On the sixth day, we realised no safe place remained in Kigali so we joined the exodus – trying to be as unobtrusive as possible at the roadblocks manned by machete-wielding militia men. It felt like the whole of Kigali, thousands of us – on foot, bikes, cars, trucks – were leaving at the same time.

We were heading to our family homestead in Gisenyi, an area near the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo now known as Rubavu district.

This time when I did the journey, retracing our path to safety, the traffic flowed smoothly and there were no gunshots or roads lined with people fleeing. This time it was a quiet, sunny, beautiful day.

I found our three-bedroom house, which for some of the three months of the genocide sheltered about 40 people, still standing – despite the fact it has been empty since we left it in July 1994.

And I was fortunate enough to meet up with some relatives who survived, including my cousin Augustin, who was 10 years old the last time I saw him in Gisenyi.

Hugging him felt like a dream – those you wake up from smiling, your heart full. My favourite memories of him are of us running in the nearby vegetable fields, enjoying what to us felt like an extension to our Easter holidays – unaware of the coming danger.

He is now a father of four – but we picked up where we had left off, catching up on our journeys since we became separated after fleeing into DR Congo, then called Zaire.

“I fled alone without my parents and went through the countryside, while my parents passed through Gisenyi town to Goma [the city over the border in DR Congo],” he said.

I can’t imagine what it must have been like for him, a young boy alone without his parents in what became the vast refugee camp of Kibumba. At least I had my family with me when I fled.

Luckily some former neighbours he was with eventually got word to his parents – a time before mobile phones – and they then all remained in Kibumba for two years.

“In the first days, life there was very bad. There was a cholera outbreak and people got sick, thousands died from the disease because of poor hygiene and lack of proper diet,” he told me.

His story mirrors mine to a point. I remember those first weeks as a refugee in Goma when bodies were piling up on the city’s streets before my family managed to organise more permanent refuge in Kenya.

But back in Rwanda, another young person – 13-year-old Claudette Mukarumanzi – was living through a nightmare of multiple attacks over several days.

It is a miracle she survived. She is now 43, has grandchildren and agreed to tell me some of her experiences – along with one of those responsible for her scars.

One of the assaults she described happened just a few metres away from where we met in Nyamata, a town in south-eastern Rwanda.

This was in the Catholic Church where hundreds of people had gone for refuge but were hunted down and killed, often by people with machetes.

“He stood inside the church when he cut me. He was singing when he was slashing me. He cut me in the face and I could feel the blood run down my face.

“He ordered me to lie down on my stomach. Then he stabbed me in the back with a spear. I still have those scars today.”

She got away after managing to reach behind her to remove the spike lodged deep in her back.

Staggering to her neighbour’s house, she thought she would be safe.

But the teenager then came face to face with Jean Claude Ntambara, who was then a 26-year-old police officer.

“She was hiding in a home whose owner called to us and said there were ‘inyenzi’ there,” Mr Ntambara told me.

This term means “cockroach” and was used by the Hutu hardliners and in media broadcasts to describe Tutsi people.

“I found her sitting on the bed, already deeply wounded and covered in blood. I shot her on the shoulder to finish her.

“We had orders not to spare anyone; I thought I had killed her.”

Yet after some time, she did escape from the house and wandered alone until she met someone she knew who tended her wounds.

Fully recovering, however, has been much harder – especially given that over the years, she has had to see her attackers on the streets.

With wounds this deep – both visible and invisible – how can people move on?

Ms Mukarumanzi and Mr Ntambara are among those who have, amazingly, found a way.

As I walked towards them, I was surprised to find them laughing together under the shade of a leafy tree. But their laughter belied how difficult the process has been.

When I asked the former police officer if he knew how many people he had killed during the genocide, he silently shook his head.

The young man was eventually charged and sentenced to more than 10 years for his role in the massacres.

Instead of serving time in prison, he did community service after demonstrating remorse and a willingness to ask for forgiveness.

He sought out Ms Mukarumanzi. However, it was only on the seventh time of asking that she agreed to forgive him.

“I had to face up to my own actions, recognise the role I played, and not just because of the orders,” he said.

Alexandros Lordos, a clinical psychologist who has done field work in Rwanda, says it takes collective healing to initiate personal healing.

“The violence was so intimate, where neighbours attacked neighbours and family members attacked family members. So there is a sense of not knowing who can be trusted any more,” he told me.

“The ultimate stage of healing is to start forgetting the identity of survivor and perpetrator.”

For Ms Mukarumanzi, it has been more about considerations for her own family.

“I felt like if I died without forgiving him, the burden could be on my children. If I died and that hatred still lingered, we wouldn’t be building the Rwanda I’d want for my children, it’d be the Rwanda I grew up in.

“I cannot pass that on to my children.”

Many other reconciliation initiatives have been set up. One is a Christian-led project which brings a perpetrator and their victim together via cattle, which are hugely important within Rwandan society.

By jointly caring for one cow – and engaging in conversations about reconciliation and forgiveness – they build a better future together and one day hopefully a herd.

Rwanda has made strides to unify the country once so divided on ethnic lines – in fact it is illegal to talk about ethnicity.

Critics, however, point out the government stomachs little dissent – dissidents are often charged with genocide denial. Certain freedoms are lacking, which could stifle long-term progress, they say.

There may still be some way to go to overcome the past, but it is happening – as I witnessed on my trip.

It has taken three decades for Rwandans to reach this point of reconciliation.

For me to finally return; for Ms Mukarumanzi and Mr Ntambara to live together again as neighbours.

For us all to find a place for our collective and individual traumas – a space we can heal, alone and together.

The startling realisation for me has been that Rwanda, while it will always hold a piece of my heart, no longer feels like my home.

But I have made peace with that on this journey, which has also helped to heal my wounds and allowed me to accept what I have lost.