In our series of letters from African journalists, Maher Mezahi writes about what looking for the branches of his family tree has taught him.

On the outskirts of Skikda, an agreeable Mediterranean city along Algeria’s eastern seaboard, my extended family owns a plot of land that sits on a slope.

For my mother and her siblings, the land was an idyllic escape from their cramped downtown apartment that was synonymous with the mental grind of the school year.

On long summer vacations in the countryside, they cautiously picked juicy prickly pears, carelessly built large bonfires and invented creative outdoor games to pass time with cousins.

For my generation, visiting the land usually meant a day without a mobile phone signal and avoiding the orange-striped garden spiders that were the size of my palm.

Nonetheless, all of us are unanimous in recognising the value of the land, mostly because of what sits on the slope’s peak.

A curving dirt path leads to the top, where our family cemetery sits in peace.

Only the rustling of the fragrant leaves from an adjacent, majestic eucalyptus tree breaks the quiet.

Every family trip to Skikda, without exception, is always punctuated by us visiting those who have passed on.

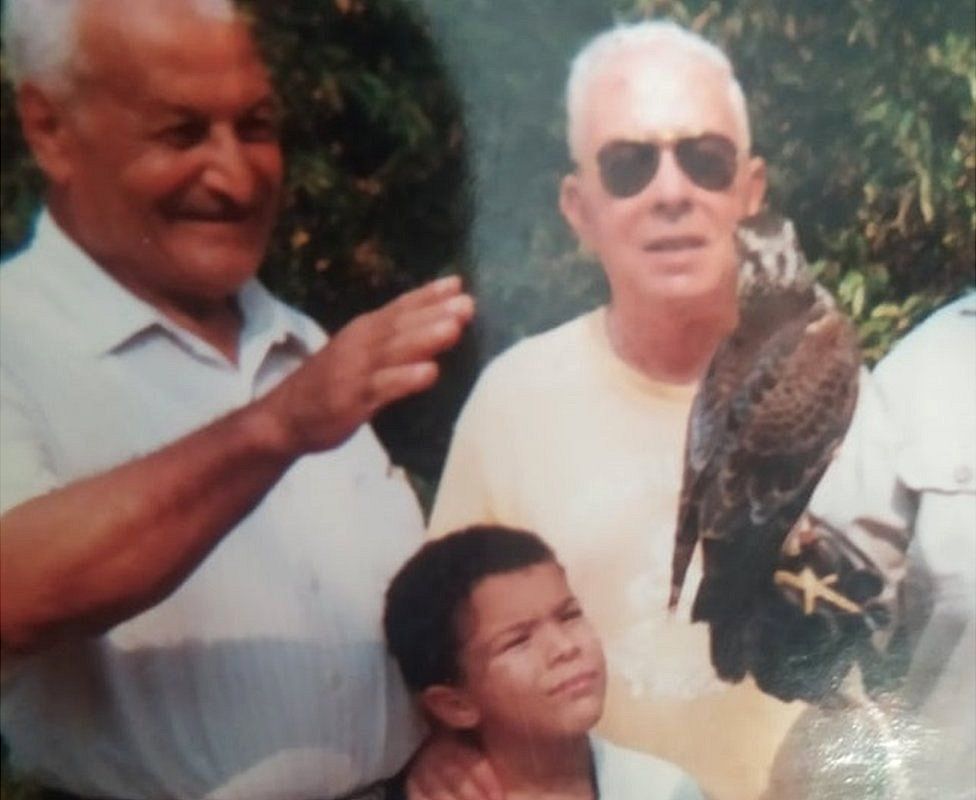

A whole host of people who meant a lot to me now rest on the hilltop, including my maternal grandmother and grandfather.

After taking a moment with them, I usually search for the resting place of my great-great-grandfather, Ahmed.

Thick, green paint on the small boulder that serves as his tombstone indicates that he was born in 1845.

It always hits me that this is the furthest I can dig back into my personal history.

It is not at all common for people in my country or on my continent to be able to locate the graves of their ancestors four generations up, and I quickly come to terms and appreciate that privilege I have.

In the absence of modern municipal registers and death certificates, the majority of us rely on oral testimony to construct our family trees.

Across many cultures in Africa the ancestors are revered, but sometimes specific information is elusive.

Over the past few weeks, I have been going through my phone contacts and took a straw poll from colleagues to see what their respective experiences were tracking their ancestry.

Colleagues in Ghana and South Africa confirmed that the exercise was mostly oral and came from uncles or siblings of grandparents – they could climb the family tree but only reach three generations above them.

Women left out

A friend in Ethiopia told me that in parts of his country “children are obliged to memorise the generations above them”.

The naming tradition also remembers fathers and grandfathers.

I also know from friends that it is customary in Egypt for children to be given their father’s and grandfather’s first names as middle names.

Yet, such techniques can be shallow and are often patrilineal, meaning that the women of the past are more prone to be forgotten than their partners.

At times, I yearn for the wealth of recorded information available to populations elsewhere in the world.

In France, for instance, the government has digitised and uploaded important documents such as marriage, birth and death certificates onto a database that is accessible on a government website.

In England and Wales there are records for all births, marriages and deaths registered all the way back to 1837.

Unfortunately, I believe that we are still decades away from African citizens gaining thorough access to digitised civil documents on a large scale.

But why does it matter?

There is the cliché that “if you don’t know where you’re from, you don’t know where you’re going”.

I have ruminated on that question a lot over the past few months.

One of the main benefits of learning your personal history is that you can educate yourself about yourself.

With the right information, you may find the origins of your own physical features, medical history or personality traits.

I am also at that stage of my life where I am beginning to think about future generations and the importance of passing down a cultural identity.

But I think the most important lesson I learned from looking into my personal history was a deep attachment to where I am from.

It is not necessarily about a flag, a country or an ideology. Instead, I think back to that parcel of land in Skikda, and how it has directly nurtured my family and indirectly nurtured me, for more than a century now.

I think back to that eucalyptus tree, and how it perhaps provided shade for my great-great-grandfather, Ahmed.

That understanding is humbling because it places me directly in the cycle of life, and it also brings about a level of gratitude that could completely transform the way in which I live.