It was an unusual hijacking by a group of three men, two women and three young children. They were Black Panthers who commandeered a Delta airliner, flew across the Atlantic and the adults never set foot in the US again, four of them making France their permanent home.

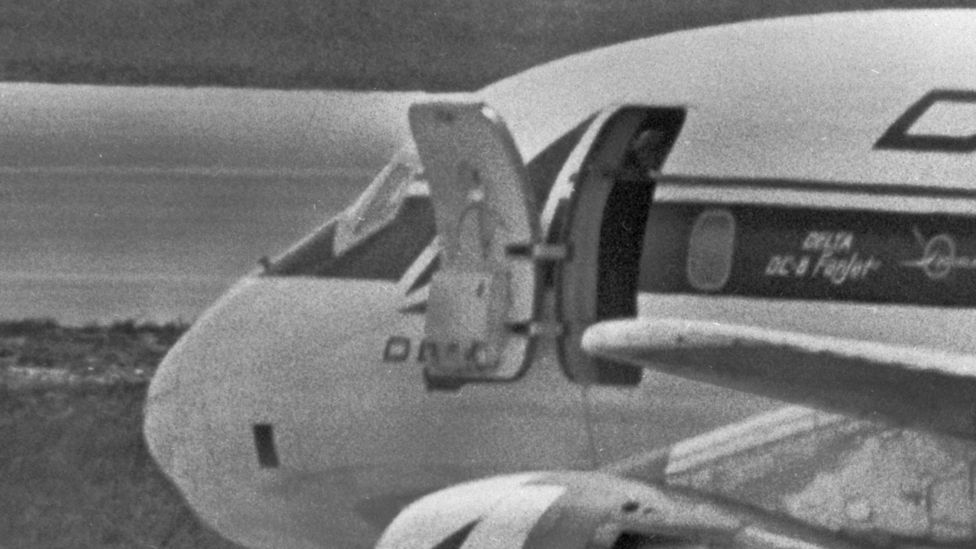

An airport vehicle driven by a man in swimming trunks approached the Delta Airlines DC-8 standing on the tarmac of Miami airport in the summer heat. The vehicle’s passenger – also wearing swimming trunks – stepped out, carrying a heavy blue suitcase under his arm, and walked until he was under the open door of the airliner’s fuselage.

A rope dropped down, and the suitcase was hauled up. Inside was $1m.

The men in trunks were FBI officers, whom the hijackers had insisted wear no clothes to ensure that they weren’t armed – though one later claimed to be carrying a gun in his trunks anyway.

Once the money had been checked, the 86 passengers on the flight from Detroit were released and the empty plane took off again, heading for North Africa via Boston.

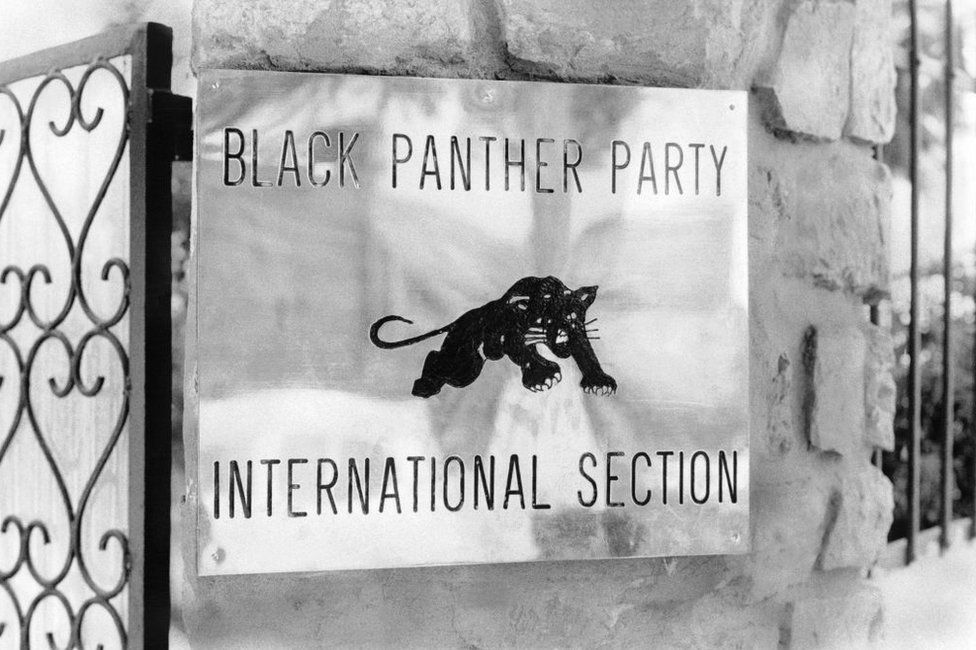

It was 31 July 1972, and this was the second time in little over a month that hijackers were trying to reach the Algerian headquarters of the Black Panther Party – at that point the most powerful black power movement in the US.

Two of the hijackers were Melvin McNair, 24, and his 26-year-old wife Jean. When they had met at university in North Carolina seven years earlier, no-one could have predicted they would end up being charged with air piracy – an offence carrying a 20-year minimum sentence, and a maximum of death.

McNair had grown up in Greensboro, North Carolina, where he excelled in baseball – his team became the state champions in the black league. White teams wouldn’t play black ones, that was just the way it was, he says.

He also played American football and his studies at North Carolina State College were supported by a sports scholarship – until he took part in riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968. McNair was instantly dropped from the football team, lost his scholarship, and his studies came to an end.

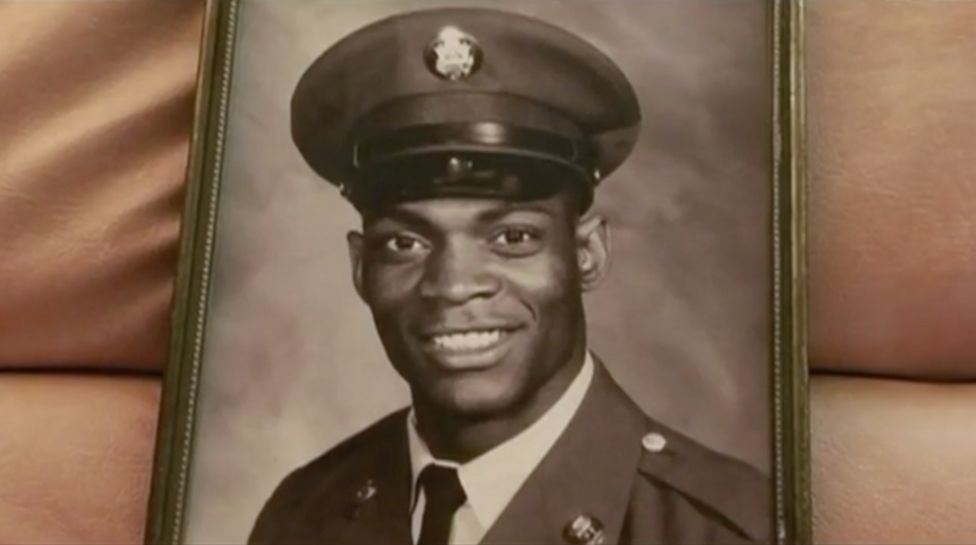

But it was when he was drafted into the US Army the following year that he really discovered institutional racism, he says.

Stationed in Berlin, he witnessed Ku Klux Klan-style cross burnings on US military compounds, and some of his fellow black soldiers got beaten up by white supremacists in the barracks.

“Racism was not hidden, so we started discussing militant action. We started to resist passively by refusing to salute officers, we wore black armbands, grew our hair long and didn’t stand up for the national anthem,” he says. “At the same time the Black Panthers movement back in the US was looking to extend its reach internationally and came to Berlin to talk to us and recruit us – and that’s when I joined the Panthers.”

Jean had joined McNair in Berlin and when, in 1970, he was told he would soon be sent to fight in Vietnam, she was just about to give birth to their first child. Later that year they flew back to the US, supposedly to find somewhere for Jean and their son to live while Melvin was away. Instead McNair deserted, and the couple went underground in Detroit, which was at that time a hive of black militancy.

In Detroit they ended up sharing a house with two other men on the run from the law. One, George Wright, had been convicted of murder after a botched robbery that left a petrol station owner dead, but McNair and Jean were unaware of this – it wasn’t considered appropriate to ask questions about each other’s past. When the other man, George Brown, was shot by Detroit police, fortunately sustaining only minor injuries, this intensified their determination to leave the US.

The group’s sights turned to Algeria, where the charismatic Black Panther leader, Eldridge Cleaver, had been welcomed after getting into trouble with the law in the US, and opened a branch of the party. But how were they to get there? The men came up with a plan.

In the early 1970s hijackings were far more common than now. McNair says they did their research by spending time at Detroit airport and asking lots of questions.

“That period of time was crazy, everything was crazy, everything was full of madness but we studied hijacking and we looked at the weaknesses and the strengths of that kind of operation,” McNair says. “We had to pick a plane that could do the whole route and cross the Atlantic. That’s why we chose the plane we did.”

They adopted disguises. George Wright dressed as a priest, George Brown as a student, and McNair as a businessman. Travelling with them were Jean and George Brown’s girlfriend, Joyce Tillerson. By this stage Jean and McNair had two children, while Brown and Tillerson had one.

Somehow they smuggled three small handguns on board. One story goes that they were hidden inside hollowed-out Bibles, and that when the metal detectors went off, security guards assumed it was because the women were wearing jewellery. McNair’s caginess about the details, even now, suggests that there was more to it and that maybe they had help from an airport employee.

Once Delta Air Lines flight 841 from Detroit to Miami was airborne the hijackers let the passengers eat their meal before springing into action.

But even after making their demand for $1m and a flight to Algiers they tried not to frighten anyone.

“We didn’t want to create a sense of panic, remember we had three children travelling with us too,” McNair says. “We even tried to make the mood lighter by playing a cassette of soul music including Stevie Wonder, The Temptations and the Four Tops.”

Once they landed in Miami negotiations with the FBI began. At first the police said they could only come up with half a million dollars, so the hijackers said they would keep half of their hostages and take off. George Wright, the hijacker dressed as a priest, also told the negotiator he was ready to shoot a hostage.

When the FBI backed down and agreed to provide the full sum, McNair says he was the one who took the risk of appearing at the door and tugging the ransom up to the plane.

Some passengers were disappointed they wouldn’t be able to collect their luggage until the plane came back from Algiers, but no shots were fired during and no-one was physically injured.

If everything seemed to be going to plan there was one important detail they hadn’t factored in. The pilot, Capt William May, had never flown across the Atlantic before, so they had to fly first to Boston, where an experienced navigator climbed aboard – also in swimming trunks.

The rest of the trip passed peacefully. While the male hijackers went to sleep, the two women watched over the crew and four stewardesses on the overnight flight.

When they arrived in Algiers, the plane was ringed by soldiers and an official walked up the steps to the plane. His first words were, “Bienvenue chez vous!” (Welcome to your home.)

McNair says the pilot was the real hero.

“When we arrived in Algiers we offered to pay the pilot for his services but he said, ‘No thank you.’ The pilot had persuaded the FBI and their sharpshooters that everything was calm on board. As we left the airplane we said, ‘That’s a job well done.’ But afterwards we thought of how many things could have gone wrong.”

The hijackers quickly realised that settling in Algeria was a strategic blunder. Most of the dozen or so Black Panthers who had congregated there were packing their bags or had already left, and relations between the Algerian government and the US were warming up.

The hijackers were told to hand over the $1m, which was sent back to the US – to the annoyance of the few Black Panthers remaining in Algiers, who seemed much more interested in the money than in the hijackers themselves.

Over the next 14 months they lived in constant fear while housed in a compound in a suburb of Algiers – surrounded by strange and mysterious agents, some Algerian, others foreign including, McNair believes, US Navy Seals.

McNair and Jean immediately realised they would have to send their children back to live with relatives in the US.

“Nothing is enjoyable about living a clandestine life. You are living in constant danger, you don’t know what is going to come through the door, you sleep with one eye open. You are trying to be discreet – there is a lot of tension,” says McNair.

“We knew the Panthers were leaving and we would be left holding the bag. They had outworn their stay – time had run out for the Panthers in Algeria.”

Once again McNair and Jean fled, along with George Brown and Joyce Tillerson – this time to Paris, via Geneva, using fake passports and the support of international human rights groups. Arriving in Paris in autumn 1974, they lived with French sympathisers and supported themselves by doing odd jobs. Their cover story, if anyone asked, was that they had fled the US to avoid being called up to fight in Vietnam. The greatest hardship they endured was the separation from their children.

When inevitably they were arrested by the French police in 1976, the US tried to extradite them but the French court accepted the argument that the case was political, and that it was American racism that should be on trial. But they had to be tried for hijacking in a French court and were held in pre-trial detention for two-and-a-half years.

After the trial, the two women were released so that they could look after their children. McNair received a five-year jail sentence for the hijacking but it was reduced for good behaviour and for showing willingness to learn French. George Brown was in jail for longer, McNair says, because he didn’t try to learn the language.

McNair finally became a free man in May 1980 and the family was reunited again, after a break of eight years.

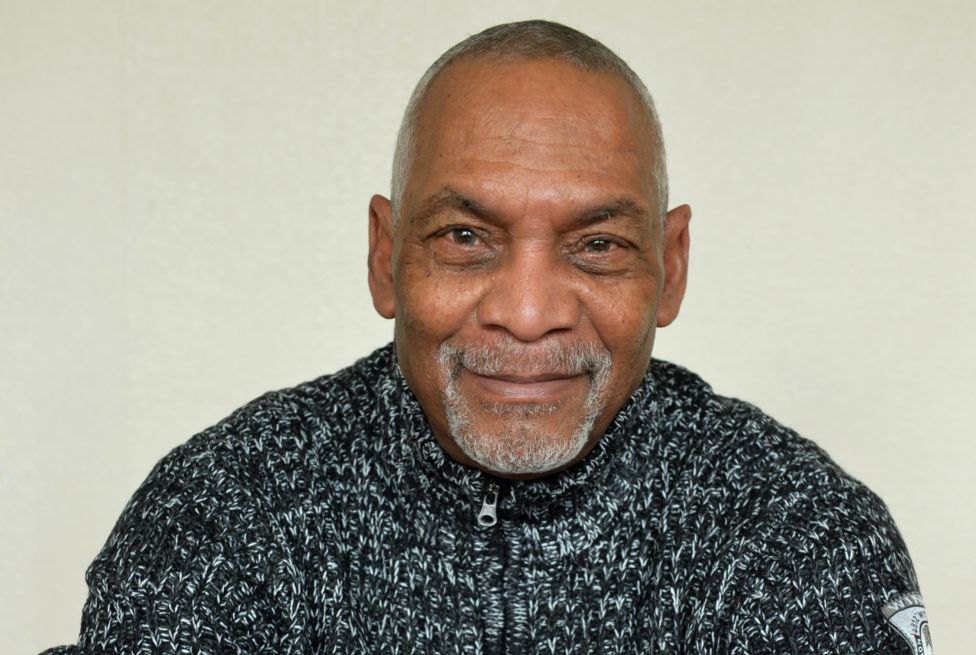

McNair retrained as a social worker and sports coach and along with his wife Jean moved to the coastal town of Caen in Normandy in the early 1980s. Since then he has worked for charities on impoverished housing estates in a neighbourhood known as Grace de Dieu (Grace of God) on the outskirts of the town, and taught hundreds of local kids how to play baseball at the local club, Phenix Caen.

The club’s ground is even named after him and Jean, who also worked on social equality issues. His message to the kids is simple: “What I went through and what I learned from the experience is good, and I made it through, which is good. So I can talk about it with kids at schools, and certain kids who don’t want to listen hear my story and that’s a wake up call to them – that they should do things differently, studying, working hard and respecting each other.”

Jean died a few years ago and Melvin, now 72, continues to work as a mediator in the community. His role includes helping families understand where they can turn if they are facing financial difficulties, and trying to improve relations between kids on the estates and the local police.

“The only thing that has changed is that I don’t get paid any more and I’m too old to play baseball,” he chuckles.

Two of his three children are French. The oldest, Johari, returned to the US and was shot dead in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in 1998, at the age of 28. McNair says it appears he was in the wrong place at the wrong time in a turf war over drugs and stood up to one of the gang leaders.

“Everything I did was for him, and to protect him,” he says, with tears running down his face, in the 2012 documentary Melvin & Jean: An American Story, directed by Maia Wechsler. “And then I lost him.”

Both his son and wife are buried in Caen and he says he will be too.

Of the other hijackers, Joyce Tillerson ended up working for the South African embassy in Paris, and died of cancer in 2000. George Brown also remained in Paris, and died five years ago.

The fifth, George Wright, went his own way to Guinea-Bissau in West Africa and then disappeared from the radar for decades, resurfacing in Portugal with Portuguese citizenship, where he lives to this day despite US efforts to extradite him.

The pilot, William May, visited France for a happy reunion with the McNairs in the documentary, Melvin & Jean. They shook hands and hugged each other and bore no ill feelings. After the hijacking May went from flying domestic flights for Delta to international flights – a step up.

McNair says he misses family back home, but he knows that if he returned he might be arrested, and he says he has no intention of going back to jail.

He has admiration for the Black Lives Matter movement but worries when he hears about black militia taking up arms and training, even if their motive is purely defensive. He points to the Black Panthers, who had legitimate concerns about racism, he argues, but by taking up arms gave the US authorities a reason to wipe them out.

And as for the hijacking that transformed his life, does he regret it?

“I always have regrets, in the sense that if you were more intelligent and less naïve you wouldn’t have made the mistakes that you did. I regret the racism that forced me into the desperate situation that forced me to react in the way I did. I regret that it has forced me into exile away from America and my family but I got a second chance to make positive change in the community I am in now.”

Watch the trailer for Maia Wechsler’s documentary ‘Melvin and Jean: An American Story’