In the middle of the last century, thousands of students from African countries were studying at Irish universities. Some had children outside marriage, who were then placed in one of Ireland’s notorious mother and baby homes. Today these children, now adults, are searching for their families.

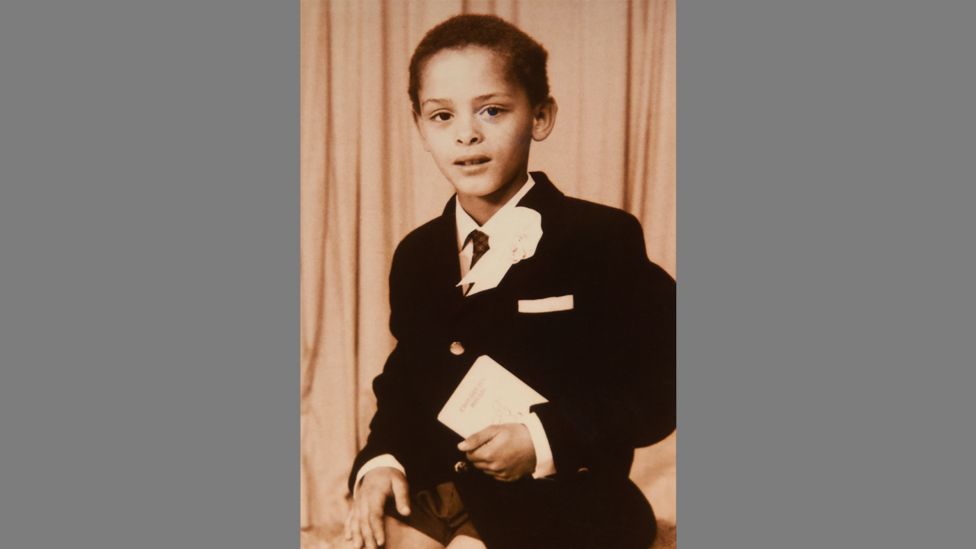

As a child, Conrad Bryan wondered if his father was a king. He was from Nigeria – or so he had been told – a place Conrad imagined was far more exciting than the orphanage outside Dublin where he lived.

“When you want something and you can’t have it, your imagination takes over,” he says.

Despite his persistent questions, the nuns couldn’t tell him anything about his father’s family – or about kings in Nigeria. In 1970s Ireland, the only things he learned about African countries were from the TV, or stories about the black children pictured on the charity boxes people would donate money to during Lent.

When a missionary priest who had returned from Nigeria came to the orphanage, he spoke to Conrad, who was fascinated by his stories of Nigerian tribes. The priest told the boy his father might not have been a king exactly, but a doctor who studied in Ireland.

Conrad worked hard at school and as he grew older longed to find a job, so that one day he could afford to travel to Nigeria. The one detail he had been told about his father was his surname – Koza.

Conrad was born in Dublin in 1964 to an Irish unmarried mother. He spent his early life in one of Ireland’s infamous Church-run, state-funded mother and baby homes, St Patrick’s on the Navan Road. At that time, most unmarried women didn’t keep their children. The stigma made it impossible to get a job or rent a flat, and there was no state support available for women in this situation.

Conrad’s father was one of many African students who had come to study in Dublin. In the 1960s, the Irish government ran schemes supporting them in learning skills that would help them build up their own newly independent states. Most enrolled in Trinity College, University College Dublin, and the Royal College of Surgeons, studying subjects like medicine, law, and government administration. By 1962, at least 1,100 students – or one tenth of Ireland’s student population – were African, from countries like Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa, where there were strong links with Irish missionaries.

By 1967, an Irish military college had accepted a delegation of Zambian cadets. “It’s natural… that Zambia’s young officials would be trained in a small independent country like Ireland, a country with no history of imperialism,” a TV news report said at the time.

But the students weren’t always welcomed by the wider population. News articles reported attacks on African students and mentioned “difficult landladies” – a reference to housing discrimination, according to Dr Bryan Fanning, author of Migration and the Making of Ireland. Though some of the students had relationships with Irish women, it was rare that these led to marriage in the culture of the time.

Many of the children from these relationships spent their early lives in mother and baby homes. Irish adoptions at the time were carried out under a closed system – where there is no contact or sharing of information between the adopted child and the natural parents. To this day, adopted people do not have a statutory right to their early life files. Others, like Conrad, who were not adopted, were transferred to orphanages. For a child born outside marriage, their father’s name would not typically have appeared on their birth certificate.

Some have spent years trying to discover their heritage.

In the late 1980s, Conrad had grown tired of being called names. There was an added stigma attached to the colour of his skin – people automatically assumed he had come from an orphanage. So he left Ireland for London, where he found work in an accountancy firm.

But he still had to deal with surprised looks when he said he was from Ireland.

“Being constantly reminded that you’re not Irish is painful,” he says. “I really struggled with that. I didn’t know what my background was.”

When he was in his 20s, Conrad decided to look for his family. A nun at the orphanage contacted an Irish social worker and eventually, he got access to more of his personal records. His father’s name was not on his birth certificate, but on his records, it was listed as Joseph Conrad. There was no reference to the surname Koza.

The social worker contacted his mother, who shared what she knew. For five years, it was a frustrating back and forth between the social worker, the religious orders, his mother and the Royal College of Surgeons (RCSI). Finally, he received a letter from the RCSI revealing his father’s full name – Dr Conrad Kanda Koza.

But there was more. The letter confirmed that Conrad’s father was South African, not Nigerian, as he had been told.

“That was a huge shock. I look back on it and think, ‘What a lie I had been living.'”

The next steps of the search were down to him. He visited the British Library Newspaper Library in Colindale, north London, where he found South African newspapers and even a South African phone book. He then began cold-calling all the Kozas listed as living in Johannesburg. Eventually he got through to someone who could help him. Within a week, he received a telegram from a cousin, who put him in touch with his father’s sister.

His father had passed away in London many years previously, but the rest of the family welcomed Conrad warmly.

“They looked at a photograph and they claimed me straight away. It was a great affirmation of who I am, and who I should have known I was.”

His aunt Thuli Koza visited him in London and gave him items that had once belonged to his father – his student card from the RCSI, and a letter he had written to the family in Zulu while living in Ireland. Over beers in the evenings, she told him about the family’s history. At one point, they were close to South African political exiles in London.

He kept up with the family in South Africa, honeymooning there with his new wife and visiting often after that.

“I missed so much growing up,” he says. “It’s not just about your father, it’s about your roots – your cousins, your uncles.

Many other mixed-race Irish people, however, are still searching for information, decades after leaving homes and institutions.

Jude

Outside a basement 20 yards from Dublin’s O’Connell Street – a busy thoroughfare lined with monuments to Irish independence – a handwritten sign points passers-by towards the Rapid Tailoring Alteration Service. The shop belongs to 79-year-old Jude Hughes, a tailor and long-standing anti-racism campaigner. For more than 30 years, Jude has sat in front of his machine altering garments, alongside photos of his children, and buttons stored in sweet containers.

Like Conrad, Jude spent his early life in St Patrick’s mother and baby home. He was born on a spring day in 1941, to an unmarried machinist. His father, he would later be told, was from Trinidad. The rest of Jude’s childhood was spent in institutions – first in a convent, later in an industrial school. Growing up, he rarely saw another black person.

“You’d wonder why you weren’t like all the others. There would be no explanation, and I’d be embarrassed.”

At 16, Jude trained as a tailor and went to work in Dublin. His ears pricked up every time he heard news on the radio about the civil rights movement in the US, or the achievements of black boxers like Joe Lewis. But the reality for him was being passed over for certain positions at work. In the early days, some customers in the tailoring shop avoided dealing with him.

“They’d see me and they would freeze. Some would say, ‘Ah I think I’m in the wrong place.'”

Still, Jude carried on, brushing off racist comments in the street. “I got on with the business of getting on with my life,” he says. He joined a band and played basketball. Later, as customers began to trust him, he set up his own business.

When his first son was born, Jude was desperate to share the good news, but he had no family members to ring, just the friends he had acquired over the years. As his son grew older, he started to ask questions. For a school project, he had to make a family tree, and Jude remembers the shame he felt at not being able to help him.

“There is nobody you can say is a relation of yours.”

Over the years, Jude watched from his shop as the city changed and faces like his own were more visible. In the 1980s, he became a founding member of one of the first anti-racism groups in Ireland. People of African descent greeted him on the street, claiming him as one of their own. But his own searches continued to yield little about his heritage. From his correspondence with the Irish authorities, he knew his mother’s name, her occupation, and the county she was from, but nothing about his father – no evidence that he was from Trinidad.

In 2015, the homes Jude and Conrad spent their early lives in became the subject of a government inquiry, the Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation. The treatment of women and girls who gave birth there, high infant mortality rates, forced adoptions, and vaccine trials were all being investigated.

By then, Jude and Conrad were members of a group, the Association of Mixed-Race Irish (AMRI). The AMRI lobbied the government to examine the specific experiences of mixed-race people. Alongside their common experiences of racism and being cut off from their mixed-race identity, they asked for details about why it appears that mixed-race children were less likely to be adopted and more likely to be transferred to other institutions.

The government agreed to insert a clause requiring the commission to identify cases of racial discrimination in the homes.

Conrad and Jude, along with many others, submitted evidence about their experiences, and the final report will be published soon.

Now Conrad is helping Jude, and others looking for answers about their background.

An accountant and auditor by trade, Conrad was a whizz at spreadsheets and charts, uncovering things that people preferred to keep hidden. He has, however, encouraged people to first engage with social workers for support.

“People are so lost. It’s part of the shocking story of lost identity and the shame of having a black father.”

Conrad had also acquired a wealth of knowledge over the years. He discovered that there had been a great deal of media interest in the African students who studied in Ireland in the early decades of independence. He’d learned, too, about freedom of information requests, and how helpful the universities could be.

Another useful resource were ship passenger lists, and he had found out how African students had made the journey to Ireland. This is the sort of highly-specific information that Irish social workers would not be trained to find, and a combination of these sources had enabled him to successfully track down the Nigerian father of another member of the group.

In Jude’s case, he set up his family tree on Ancestry.com. By researching publicly available birth and marriage certificates, they found the town Jude’s mother was from, and some more information about her family. The charts revealed an unexpected biological relative for Jude – Conrad is a distant cousin on his mother’s side.

On his father’s side, they have worked with a genetic genealogist. DNA testing has revealed that Jude’s father is most likely Nigerian, not Trinidadian as he had been told. Inputting this information into Jude’s Ancestry chart, Conrad started to search for DNA relatives. A distant cousin has been tracked down and has agreed to a DNA test to help narrow things down.

Marguerite

Through their work with AMRI, Jude and Conrad continue to meet people much younger than them, who are only embarking on their search for their African heritage.

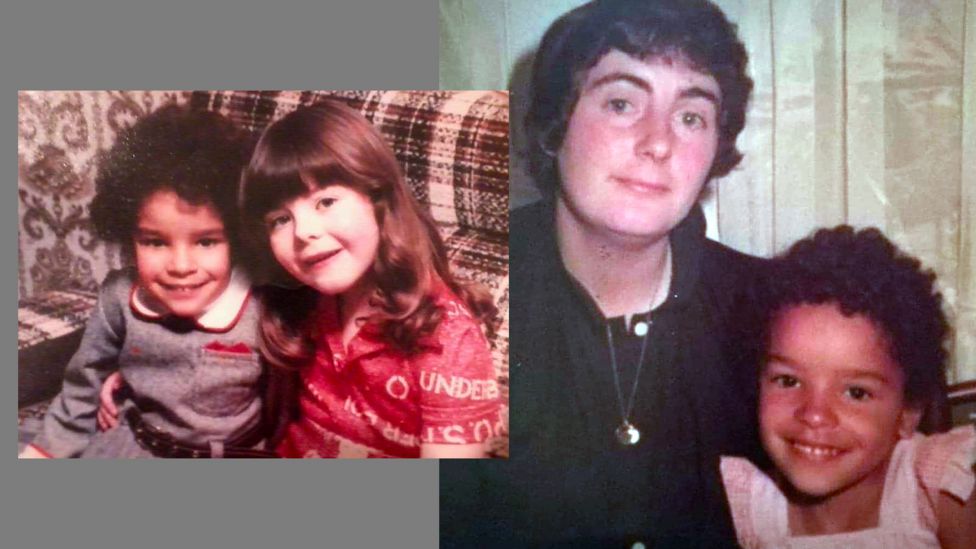

Marguerite Penrose was born in 1974, spending three years of her early life in St Patrick’s mother and baby home.

Marguerite’s experience, however, was different in some ways from that of Conrad and Jude.

She was fostered, and eventually adopted, by a family in Dublin, with whom she enjoyed a happy childhood in the north of the city. She was surrounded by supportive extended family and many friends.

But as she got older she became increasingly aware of how different she was to others in her neighbourhood. She also spent long periods in hospital receiving operations for congenital scoliosis, and was frustrated that she couldn’t answer any questions about her medical history.

“It’s another complete part of your genetics that you know nothing about. As you get older, it’s very important to know if there’s heart disease, cancer in your family.”

When Marguerite’s adoptive family finalised her adoption in the early 90s, they received some background information – her natural mother’s surname, the area where she was from, and the fact that she has since remarried with other children. It confirmed what Marguerite had already been told about her natural father – that he was a cadet from Zambia, but his name or surname were not included.

For years, Marguerite wondered whether to begin a formal search but she had heard stories about the mother and baby homes, and about incorrect information that those who had been born there had been given.

“I think of my birth mother, and I think, ‘God, what did she go through? Did she willingly give me up? I don’t know,'” she says. Last year, after another spell in hospital, she started the process with social workers to trace both of her natural parents.

“To get the answers to the millions of questions that spill around your head, it would mean the world.”

The final report into mother and baby homes will include survivor testimonies and a social history of the homes from 1922-1998. An apology to those affected is expected, and Conrad, Jude and Marguerite hope the government will acknowledge the specific experiences of mixed-race people.

“We’re telling our stories in the hope that the state will learn from this. In the hope of protecting the diverse minorities we have got now,” Conrad says.

Jude wants the government to provide funding and training for researchers to help others like him find their African origins.

“Denial of our background left a big void in a lot of people’s lives. Some are terribly damaged by what they went through.”

The Minister for Children, Roderic O’Gorman, has said he is “determined” to do right by survivors and adopted people, and is “committed to introducing legislation to resolve the issues”.

But some remain sceptical things will change quickly. Most of the records collected as part of the commission will be sealed for 30 years, though a database that will assist with tracing and personal data requests will be transferred to the Irish authorities.

In the meantime, Jude is optimistic that with Conrad’s continued help he will get a result before his 80th birthday. And when his case is completed, Conrad will move on to the next one.

“It’s such a joy to help people,” he says. “It gives you back something that you’ve lost.”