Vernon Vanriel was a talented athlete who fought crack addiction, was sectioned twice and beaten up by police officers. Finally he ended up stateless in Jamaica. A new play tells his extraordinary life story.

Vernon Vanriel thinks it’s ironic that a play about his life is now considered newsworthy. “For 13 years nobody wanted to know. Nobody wanted to listen to my story,” says the former boxer. Actually, Vanriel is playing it down. For many years, the British government refused to listen to his story. And what a story it is.

The play, On the Ropes, divides his life into 12 rounds. The 11th round was exposed by the Guardian in 2018. Vanriel was a victim of the government’s “hostile environment” policy and the Windrush scandal. Despite having lived in Britain since the age of six, he was prevented from returning because he didn’t have a British passport and had spent more than two years away in Jamaica, the country of his birth. The 12th round is the here and now – his life today back home, and the battles since his return.

But the other 10 rounds of Vanriel’s life are equally fascinating, perhaps more so. And it’s only by hearing the whole story that we can really understand how Vanriel got trapped in Jamaica in the first place and had the strength to keep going.

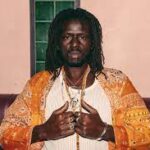

Vanriel, now a frail 67, suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure and has bipolar disorder. He lives in north London, close to where he grew up, but is not well enough to meet up in person so we speak on the phone. He is with playwright Dougie Blaxland (the pen name of James Graham-Brown), who co-wrote On the Ropes with him. Vanriel’s voice is weak, and sometimes he has to take a break to catch his breath. But what soon emerges is his profound inner strength. Here is a man who has survived pretty much everything life could throw at him and has come out battered but hopeful.

Today’s Vanriel sounds so different from his younger self. In the play, he portrays himself as a cocky motormouth, convinced he has the beating of all-comers in and out of the ring. He tells me how important it was to show us all his flaws as well as his good qualities. “Dougie said to me: I’m only going to take this on with you if you’re honest about it all. But that’s what I wanted – to tell it as it truly is.”

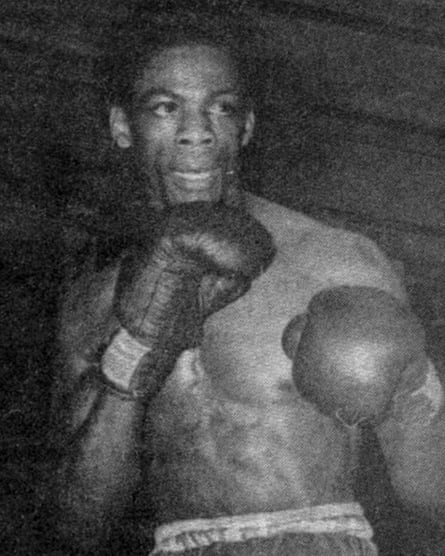

After leaving school he trained as an electrician and set up his own business. By night, he trained as a boxer and rose up the lightweight ranks. At 21, he turned professional, and went on to be managed by Terry Lawless, who also managed Frank Bruno. Vanriel had pace and grace, and danced his way to victory after victory. Fans called him The Entertainer and the Tottenham Tornado. He fought in front of thousands at London’s Royal Albert Hall, and drew comparisons with the great Sugar Ray Robinson. He entered the ring in a sombrero and flamboyant costumes, bigged himself up in verse just like his hero Muhammad Ali, and was every inch the showman. “I was a flash geezer. I’d buy cars with the stripe down the side. Ford Capris. Flash, that’s how I was. And that was a side of me that got me in trouble, too. I couldn’t keep my mouth shut.”

I was a flash geezer. I’d buy cars with the stripe down the side. Ford Capris. Flash, that’s how I was

Today Vanriel prefers to be called Josh, his middle name. Does he see Josh and Vernon as two different people? “Dougie and I talked about that a lot. I think maybe this is part of my craziness!” He laughs. “The man who walks in the ring is the outgoing show-off, the big gob. Then there’s me stuck in my flat, quiet and sometimes lost.”

It was the gob that got him into trouble just as he was heading for the top. In 1982, he gave an interview to Boxing News in which he talked about how exploitative the sport was. “The men in dinner jackets and bow ties at sporting dinners and in the audience paying big money were all white professional people. And us boys in the ring were working class. Some white, some black, but we were all working class. So it wasn’t all racism, it was class.”

For good measure, he labelled promoters a corrupt cartel. “I said some of the promoters were only there for the money and didn’t care about us guys. Looking back, I thought I was the man to speak out and maybe that was part of my cockiness; thinking I was bigger than I was.”

That was when Lawless told him he could look for a new manager, and that he would never find one. A hubristic Vanriel replied that Lawless could stick his management where the sun don’t shine because if he won his fight next week he would be Britain’s No 2 and guaranteed a crack at the No 1, George Feeney, for the British championship.

Vanriel did beat his next opponent, but he never got to fight Feeney. Lawless had put the word around. Vanriel was damaged goods. Does he wish now he’d kept stumm? “A bit of me regrets it, but a bit of me is proud because no one else would speak out.” You must think of what could have been, I say. “All the time. To have a go at that title, to be British champion, that would have been something.”

Vanriel had been a disciplined boxer. But robbed of his opportunity to fight for the championship, he fell into despair. He became a crack addict; the relationship with the mother of his two British children fell apart, and he was sectioned twice. On one occasion, he was badly beaten by police officers.

“So many boxers have the same battles,” he says. “When it’s all over, when the party’s finished, when everybody’s gone home, what do you do? How do you keep the adrenaline going? How d’you keep the blood pumping around the body? I took the wrong road to that.” Does he think his addiction would have killed him? “No doubt. I think if I hadn’t gone out of London when I did, I’d be dead.”

That was when a recent girlfriend got in touch, told him she had given birth to his child and invited him to stay with them in Jamaica. Initially it worked out well, and they lived as a family. Vanriel briefly found success as a coach, training a young boxer to the final of the Jamaican championships. But then the relationship with his new family disintegrated, and poor health did for his work prospects. When Vanriel tried to return to Britain, he found he couldn’t.

He did not know that being outside the UK for two or more continuous years meant he would lose his leave to remain indefinitely. He was now effectively stateless. Although he had a Jamaican passport, he did not qualify for benefits or healthcare there.

Vanriel found himself homeless in Jamaica, living in a disused church. One night he made a fire to keep himself warm. The fire got out of control and the police arrived. That was when he discovered how worthless his life had become. “One of the officers put his gun to my head. I believe he thought it would have been easier to kill me than go back to the police station and fill in forms. They saw me as garbage – best off without that in our society, just get rid.” While the gun was still pointed at his head, the officers received a call ordering them to attend an urgent incident. Vanriel is convinced he would have been killed if they hadn’t been called away.

He was charged with arson over the church fire. Now he was sure he would spend his remaining days jailed in Jamaica. But after more than six months remanded in prison, he was cleared and returned to life on the streets.

Meanwhile, his sisters in London were fighting for his return to Britain, and his MP, David Lammy, got involved. By now the Guardian’s Amelia Gentleman was uncovering the Windrush scandal. Numerous families who had arrived from the Caribbean between 1948 (when the Empire Windrush ship brought one of the first groups of West Indian migrants to the UK) and 1973 (the cutoff point for people arriving in the UK from a Commonwealth country to be automatically granted the right to permanently remain) were being targeted by the government. Some, like Vanriel, were refused permission to return to Britain; others were threatened with deportation or actually deported.

Emaciated, Vanriel was living in an abandoned roadside grocery shack in western Jamaica. “If I ever end up accidentally going to hell, I’ll be well prepared for it from the experience I have had here. I have deteriorated to something unrecognisable,” he told Gentleman. Soon after she wrote about him, the government relented and he was sent a first-class ticket to return to Britain.

Astonishingly, his troubles were still not done. Vanriel found himself in a catch-22 situation. The government had introduced a new requirement that people had to have been in the UK five years to the day before they made the application for citizenship. This was impossible for Vanriel, who had been locked out of the UK unlawfully. Despite having been flown over at huge expense, he was denied residency.

In 2021, he and Eunice Tumi (another member of the Windrush generation refused citizenship under the five-year rule) took the government to court. The high court ruled that their human rights had been breached when the Home Office refused to grant them citizenship.

“Winning the court case in 2021 was big, big, big! It was justice for all those people who have lived their life here, gone to school here, paid their taxes here, then were told they’re not British citizens. The government can’t suddenly rewrite the rules when it suits them. You can’t do that. So that’s a proud moment.” That said, justice for the victims of the Windrush scandal continues to be denied: this month, the Guardian revealed that home secretary Suella Braverman was rowing back on key commitments made in the wake of the scandal.

On the Ropes takes us from Vanriel’s earliest days up to the present. It is a beautifully written play, with a Greek-style chorus that reflects the voices in his head and a wonderful score of reggae classics.

What has the experience of writing it been like? “It’s been hard and tough at times. I’ve been to some dark places along the way,” Vanriel says with a hint of understatement. “But it’s kept me sane, it’s kept me in balance.”

One of the best things to come out of the play is his friendship with Blaxland. “He is my mucker,” Blaxland says. “I speak to him every day, sometimes two or three times a day. I’ve learned so much from him.” Such as? “Humility and lack of self-pity. Those petty things that worry you from day to day seem so trivial by comparison with what Josh has dealt with, and he has come through without feeling bitter or twisted. He’s a remarkable human being.”

What would Blaxland most like the audience to get from the play? “I want people to come away feeling we should never tolerate a government that treats people in such an inhumane way. There is something fundamental about compassion that should be at the heart of every administration.”

Vanriel has got his breath back. “Not just from government,” he says. “From everyone. Everyone. Right across the board. Compassion, caring for one another and respect.”

I ask Vanriel how he survived 11 years of homelessness in Jamaica, and he returns to the subject of boxing. “You’ve got to have something to get in that ring in the first place, and stand there and take the pasting. I think there’s a fighting spirit in me that made me carry on.” As he talks, I visualise him taking the blows – bipolar disorder, drug addiction, cast out of the boxing world because of his principles, cast out of his own country because of his government’s prejudice, jailed, beaten and almost shot.

And here he is still standing, talking with such dignity and generosity. Does he really have no bitterness? “I’m too tired to be angry,” he says. “There’s a lot of hate in the world. One thing I learned from boxing is when you get in the ring you respect the opponent, you don’t hate the opponent. I want to beat the government, I want them to admit what they do is wrong, but I don’t want to hate them.”