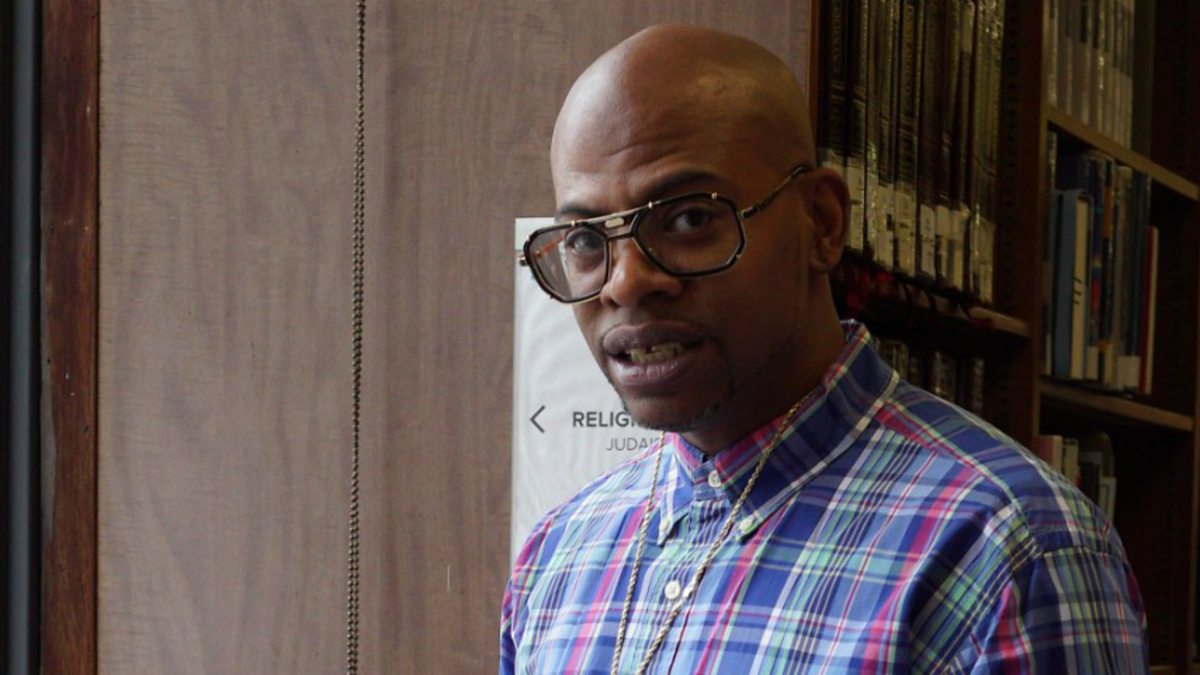

John Dwayne Bunn, a 43-year-old African-American loves his books. His all-time favourite is Sister Souljah’s ‘The Coldest Winter Ever’ where a mother advocates for the improvement of her black community as she witnesses losing her loved ones lose their lives to repetitive incarceration, violence and poverty.

John Bunn read this book over and over again, allowing the words to give him comfort and strength as he lay in his cell in a prison in upstate New York where he was serving a sentence of 20 years to life for a crime he did not commit. He could relate to it.

Now the founder of a non-profit organisation, A Voice 4 The Unheard, which sends books to prisons across the country, he also wants to change the next chapter for at-risk youth in his community.

But before John Bunn got here, life threw him a curve ball.

As a 14-year-old boy in 1991 John Bunn first found freedom while tumbling through the air doing gymnastics but his athletic prowess hid a secret he was ashamed of.

‘School was a seasonal experience because I was very athletic but I struggled and had difficulties in reading and it was a fear. Reading and writing was extremely hard for me.’

But at school even though John Bunn struggled, he somehow managed to get by without his teachers getting too suspicious.

‘A lot of times a teacher would ask me to copy something that was on the board and my handwriting was so neat that she would allow me to do it for her.

John Bunn says that he could write. In fact, he is very proud of his neat handwriting.

He liked the way it looked. But the symbols meant very little to him and one thing that helped him disguise this was his popularity. He was so popular that the other kids wouldn’t ridicule him when he struggled to read aloud.

‘I became so popular because of the sports, the tumbling and the basketball that the other kids wouldn’t ridicule me.’

The idea that no one noticed that Bunn could barely read is surprising. But the adults in his life hadn’t always given him the attention he needed.

‘I was born at the wake of my father being murdered. The day that my mother went into labour with me, was the day that my father was being laid to rest at the cemetery. I never had the opportunity to have that type of structure in the household so I believe in my earlier years my mother was just trying to get by at the time.’

Living a hard-knock life

His upbringing had been chaotic. Bunn lived in the Kingsborough Projects – social housing in Crown Heights and Brooklyn in the late 80s and early 90s. It was an area seething with crime, gun violence and racial tension.

Young black men were being arrested at rates higher than any other group in the US. Also to contend with a crack epeidemic and a record murder rates. Something that would become devastatingly personal to John Bunn.

There was a lot for him to navigate. He lived with his baby sister India and his mother Maureen.

‘My mother was my everything due to the fact that I didn’t have a father. She was playing both roles and my grandmother was very present also in my life. She was like my mum and my mother was my second mum.’

On the 14th of August, 1991, the family gathered round their dining table for breakfast when they all heard several bangs on the door. The police came knocking.

‘One morning my mum was having breakfast with my sister and we heard a bang on our door. Next thing I knew there were about 100 police officers in my house. They drew their weapons on me, my sister was panicking and my mother was trying to figure out what was going on.’

John Bunn says the police initially told him he was a suspect in a robbery and they were taking him to the precinct for questioning. His mother helpless with her baby daughter remained at home.

‘As soon as they got me out of my mother’s presence, they got me into the police car and started asking me questions and telling me I was involved in a homicide.’

It wasn’t a robbery, afterall. John at 14 years old found himself being interrogated for murder.

‘That put me in a state of fright and I didn’t understand what was going on at this time.I was put in a police line up and the others were men. I was a baby at the time but they had to actually put us in a sit-down line up because in the stand up line up, the men outsized me so much.

I was just scared for my life, I was crying a lot.’

‘I thought the system would protect me’

The man who was killed was an off-duty prison official. It was around 4am and he was in a car with his friend parked nearby Kingsborough Projects where Bunn lived. Two men approached the car and started shooting and a gunfight ensued. All of the men, the guys in the car, the guys outside were bloodied and wounded.

Maureen, his mother heard the shots and woke up. Scared, she checked in on her children – they were fast asleep. Meanwhile one of the men in the car managed to escape, the next day as the sole eyewitness he was at the police station and so was John Bunn.

‘I got picked out from the line. It was unreal. I was in the room for a couple of minutes and then there was an officer who came into the room and told me that today was my lucky day that I got picked and at that point I knew it was serious.

They were really blaming me for something I didn’t do.’

At the police station Bunn professed his innocence but he along with a 17-year-old boy who John Dwayne only vaguely knew was arrested and charged with murder.

Then a year later, the trial. On one day of the process he was with his co-defendant, Rosean Hargrove.

‘The trial came and went so fast the only thing I can really remember about it is us being escorted back into the holding cells and we were the only ones actually there at the time.

He asked me what are we going to do? Are we going to kill ourselves or are we going to fight? We took our belts off and flushed it down the toilet. Basically saying to ourselves that we are saying no to suicide, instead we are going to fight to prove our innocence.’

There were many troubling aspects to the case. For instance the fingerprints at the scene didn’t match John Bunn’s. Also neither he nor his co-defendant had any bloody injuries. Crucially though, John had been identified at a police line-up by the sole witness. So it wasn’t looking good.

During the case John’s mother wasn’t even allowed in the courtroom.

“They told my mother she couldn’t be in the courtroom because she was going to be a witness. So she sat in the hallway for basically the whole day of my trial. That was one of my scariest moments going through that day of trial because I would get a chance to glance back and I wouldn’t see my mother there and it was like a no man’s land.

I might have had a couple family members scattered in the court but at those tender ages, you feel like your mother could save your world and my mother was the biggest superhero that could actually look to at the time.’

The day’s proceedings finished and John Bunn was found guilty. At his sentencing Maureen was allowed back into the courtroom.

‘At the sentencing I was given the opportunity to read a statement but I sat there embarrassed because I was not able to read or spell.’

He couldn’t read his statement and he couldn’t even write down questions for his lawyer. He remembers feeling fragile and frustrated.

Even though he was a juvenile, he had been tried as an adult and sentenced to 20 years to life.

‘I just thought that my innocence was enough for me to prove my innocence and I just thought that that was how the process worked. I thought the system was going to protect me.’

Finding the words

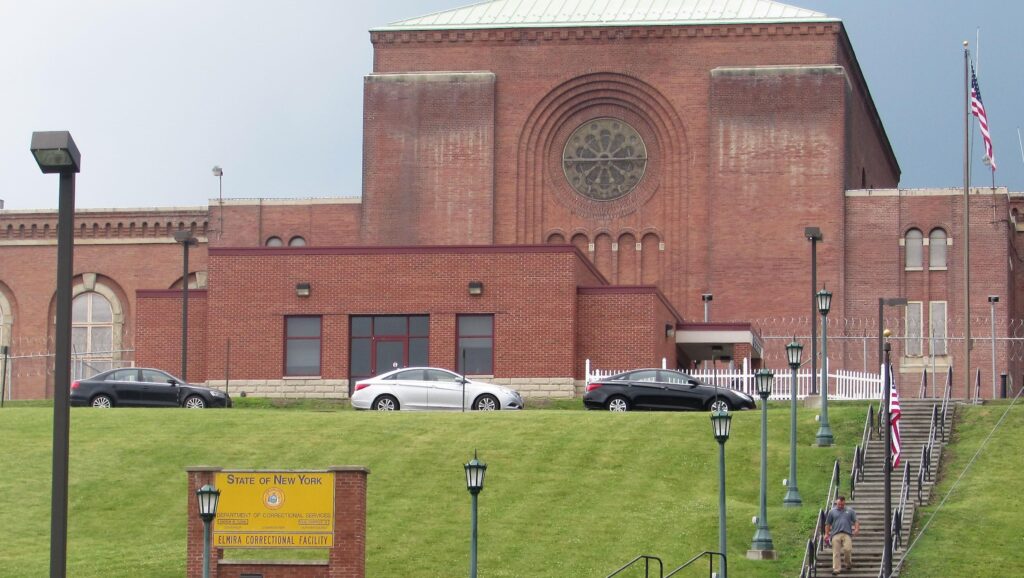

John Bunn was first sent to a youth facility in upstate New York. After he turned 17, he was transferred to prison.

‘It was like the nightmare you never wake up from and you go through a lot of turmoil. The fear heightens because as I was moving up the ladder of my incarceration, each step up was a different graduation for me and the severity got even more intense.

As I grew older, inside the system, there reality that somebody raping you, somebody stabbing you, somebody cutting you becomes your reality and it plays on who you are. I often tell people, in prison it’s often predator and prey.’

He needed to find a way to survive his misery and his elevation came through an unexpected friendship. The dictionary became his best friend.

Before John turned 17, he took classes in jail. He wanted to pass high school.

‘I ran into a teacher there that was a math teacher and even though I had all these difficulties with reading and spelling, I was one of the top people in mathematics. I never got less than a 98% or a 95%. She saw the potential I had in my ability to do math that she encouraged me to learn to read and spell. So she brought me special books including a dictionary.’

In his cell, John poured over the dictionary. Once he got a bit of the theory behind the words he would put it into practice with magazines and the like.

‘I would practice pronouncing and sounding the words. I would also pick things I like from rap magazines, practice reading and then find new words I didn’t know and then look them up.

Once I started to learn, it did something for my self-esteem. It was empowering because I was seeing myself make progress.’

Able to read and write, John started writing and responding to his mother and sister. It was a chance to be able to communicate effectively his thoughts to his family, which he says motivated him to learn how to read and write.

‘I wanted to tell her that I love her and I just wanted to be able to express myself. It took me a few months to write my first letter to my mother because it was really emotional. But when I wrote it changed our lives forever.

It was like a form of freedom to me where I could say anything and I could get my words out in time without pressure, saying it the way I wanted to say it. Before this moment, I’d get someone to read the letters she sent me.’

As John grew older, India grew older too. He didn’t want to lose her love either.

‘My sister was my joy and she looked up to me a certain way. We had a bond. When I wrote letters to my mum, I wrote to her too, giving her the rules of life because her father wasn’t in her life either. So it’s like she looked up to me to be the big brother.’

Sweet vindication: A new chapter

In 2009, after 17 years, John Bunn was released from jail. He had served the bulk of his sentence and his good behaviour helped him out in his parole hearings.

Then better news came. A non-profit organisation called the Exoneration Initiative began looking into his case.

‘When you are trying to be heard for so long, it’s like you’re continuously screaming inside this box and nobody can hear you. For you to get to that point where somebody can open that door and look at you and say, ‘I’m right here, I can help you’ and it’s really real, it’s like your heart can beat again.’

There was reason for hope. A number of convictions from the 1980’s and the 1990’s were under review. Louis Scarcella, the detective whose interrogation led to John Bunn’s arrest, appeared in court to testify in these cases. Once a star with the homicide department of the New York Police Department, the detective has retired and his legacy has become controversial.

He has faced allegations that his arrests were racially motivated and that he oversaw confessions made under coercion but he has denied all of this.

And the Brooklyn district attorney’s office has said that there was no evidence that Scarcella engaged in misconduct. Nonetheless, out of 70 cases being reviewed, 14 have so far been overturned; including in 2018, John Bunn’s.

‘I wanted to pinch myself and make sure I wasn’t going to wake up from a dream. My mother cried when she heard the news and I was on top of the world. I actually kissed the ground that day. It was the moment of my life. It was like the rebirth of John Dwayne Bunn.’