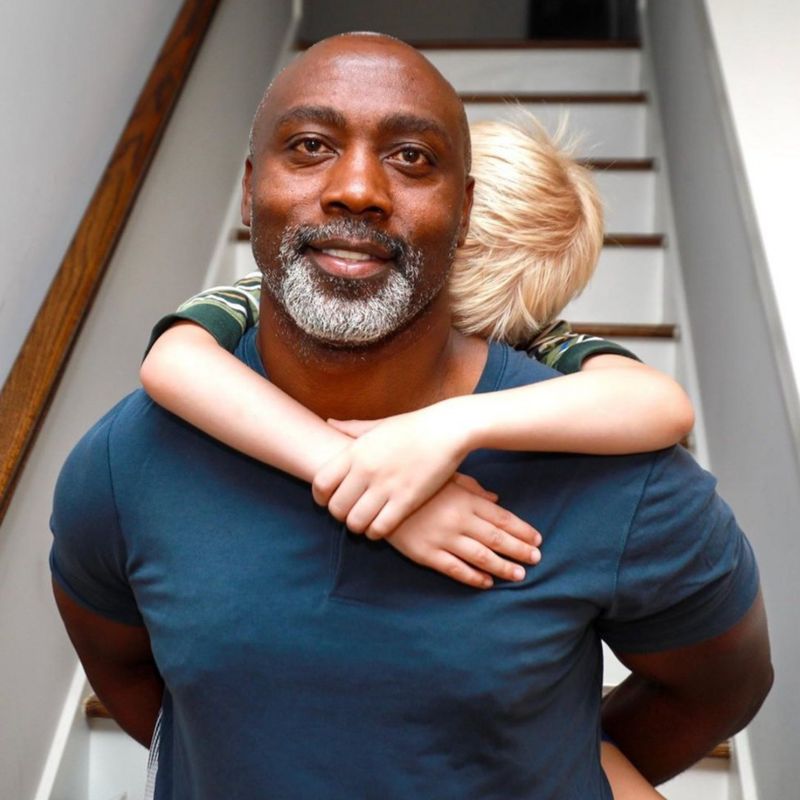

Stories of transracial adoption most often feature white families adopting black and Asian children. When the opposite happens, and black and Asian parents adopt white children, officials and members of the public can become very suspicious.

Seven-year-old Johnny was about to lose it. He’d woken up in a sulk and it was only escalating as the day progressed. Now, at a diner in Charlotte, North Carolina, Peter could see Johnny arguing with another child in the play area. He had to act fast to get his foster son out of the restaurant before a loud tantrum would erupt. Taking the boy in his arms, Peter quickly paid the bill.

As he carried Johnny to their car, the child wriggled moodily in his embrace, and was still agitated as Peter put him down to open the car door.

A woman approached them, frowning.

“Where is this boy’s mother?” she asked.

“I’m his father,” Peter replied.

The woman took a step back and stood in front of Peter’s car. She looked down at his number plate and took out her phone.

“Hello, police please,” she said calmly down the phone. “Hey, there’s a black man. I think he’s kidnapping a little white kid.”

Johnny suddenly became still, and looked up at Peter. Peter put his arm around his foster son.

“It’s OK,” he said to the boy.

On the Lonely Planet travel site, the dusty town of Kabale is described as “the kind of place most people get through as fast as possible”. In Uganda, near the borders of Rwanda and DR Congo, it serves as a transit point on the route to a number of famous national parks in the vicinity.

For Peter, his hometown still holds painful memories.

It was an impoverished upbringing. As a child, eight members of his family slept on the hard floor of a two-bedroom hut.

“There wasn’t much to hope for. If we had a meal, it was potatoes and soup,” he says, “and if we were lucky we had beans.”

Violence and alcoholism were a daily reality in Peter’s life. To escape them, he would run to the homes of his aunts, who lived only metres away.

“On one hand there was a big extended family available, and I learned that it takes a village to raise a child,” he says, “but it was chaotic.”

At the age of 10, Peter decided he would rather be homeless. So, grabbing as much loose change as he could, he ran to the bus stop.

“Which one goes the furthest away?” he asked a woman who was waiting at the stop. She pointed to a bus, and although Peter couldn’t read the sign, he boarded it. It was bound for Uganda’s capital, 400km away.

When Peter disembarked in Kampala after almost a day of travelling, he headed to the market stalls that bordered the streets and asked the vendors if he could do work – any work – for food.

For the next couple of years, Peter lived on the streets. He made friends with other homeless boys and they shared their earnings or meals. Peter says he learned an invaluable life skill: to recognise kindness in other people at a glance.

One kind man was Jacques Masiko. He visited the market for his weekly shop, and he would buy Peter a hot meal before he left. After about a year, Mr Masiko asked Peter if he would like to be educated. Peter said yes, so Mr Masiko arranged for him to start at a local school.After six months, seeing Peter thriving at his lessons, Mr Masiko and his family asked the boy to come and live with them. In Jacques Masiko, Peter found a man who treated him like a member of his family. Peter paid him back by excelling at school and eventually winning a scholarship to an American university.

A couple of decades later, Peter was in his early 40s and happily settled in the US. He was working for an NGO that would take donors to Uganda to help disadvantaged communities. It was on one such trip, when he saw a white family travelling with their adopted daughter, that Peter realised children in America sometimes needed a new home as badly as children in Uganda.

On his return to North Carolina, Peter went to a local foster agency and said that he would like to volunteer.

“Have you thought of becoming a foster parent?” the lady at the foster care office asked as she took down his details.”I’m single though,” Peter replied.

“So?” she responded, “There are plenty of boys in the care system looking for male role models, people who want to be a father figure in their life.”

There was only one other single man who had signed up to be a foster parent in the state of North Carolina at the time.

When he filled out his forms, Peter assumed that he would automatically be matched with African American children. But he was shocked that the first child that came into his care was a five-year-old white boy.

“This was when I realised that all children needed a home, and colour should not be a factor for me,” says Peter.

“I had two spare bedrooms, and I should home anyone who needed it.

“Just like Mr Masiko gave me a chance, I wanted to do this for other children.”

Over the course of three years nine children stayed with Peter, using his home as a stopgap for a few months before returning to their families. They were black, Hispanic and white.

“One thing I wasn’t prepared for was how hard it was when a child left,” he says. “It’s not something you can ever prepare for.”

Peter left long gaps between the children so he could be emotionally available for the next one.

So when he got a call late on a Friday evening from the foster agency about an 11-year-old boy named Anthony who needed an urgent place to stay, Peter resisted.

“It had only been three days since the last child had left, so I said, ‘No, I need at least two months.’ But then they told me that this was an exceptional case, a tragic case, and they just needed to house him for the weekend until they could come up with a solution.”

Reluctantly, Peter agreed and Anthony – a tall, pale, athletic boy with a mop of curly brown hair – was dropped off at his home at 3am. The next morning Anthony and Peter sat down for breakfast.

“You can call me Peter,” he said to the boy.

“Can I call you Dad?” was Anthony’s reply.

Peter was shocked. The two had barely spoken to each other. Although he didn’t yet know Anthony’s backstory, Peter felt instantly connected to him. The two spent the weekend cooking and talking. They visited the mall so Peter could buy him some clothes. They asked each other superficial questions: what food they liked, what kind of films they enjoyed.

“We were both trying to see how we would fit together.”

On Monday, when the care worker came over, Peter learned Anthony’s story.

He had been in the foster care system since the age of two, and had been adopted by a family when he was four.But now, seven years later, Anthony’s adoptive parents had abandoned him at a hospital.

“I couldn’t believe it,” says Peter.

“They never said goodbye, they never gave a reason why, and they never came back. It killed me. How could people do this?”

Anthony’s life took me back to my childhood. This kid was like me at age 10 on the streets of Kampala, having nowhere to go. And so I turned to the social worker, and I said, ‘You know what? I just need the paperwork to enable him go to school and we’ll be fine.’

Peter looked at Anthony and realised that the boy had perhaps shown great foresight.

Remember, he’d called me ‘Dad’ right away. This kid knew I’d be his dad.”

Anthony’s adoptive parents had gone to the county court to sign over their rights to him, so he was available to be placed with a family.

“I think we both knew immediately that he would be staying with me permanently,” Peter says. Within a year, Peter had formally adopted Anthony.

As they settled into their life together, Anthony wanted to hear all about his father’s life in Uganda, says Peter, because now this was his heritage too. Anthony would help Peter prepare Ugandan dishes like katogo, a breakfast of diced cassava mixed with beans.

At school, Anthony began to relish introducing Peter to his friends.

“This is my dad,” he would announce, enjoying the sometimes confused looks from his classmates.

But there have been challenging moments. On one holiday, airport security stopped Anthony to ask him where his parents were.

Anthony pointed Peter out to the officials, who immediately started carrying out a background check. Anthony became increasingly frustrated at what he saw as overt racism, but Peter calmed him down.

“I’m your dad and I love you, but people who look like me, we aren’t always treated well,” Peter said to Anthony, who was now 13. “Your job is not to get angry at the people who treat me this way, your job is to make sure you treat people who look like me with honour.”

In spring of this year, the foster agency called Peter to see if he could temporarily care for a seven-year-old boy called Johnny (not his real name), who was in need of a foster family at the start of the coronavirus pandemic. Johnny settled in as well as Anthony had, and following the example of his foster brother he too called him “Dad”.

Johnny, with his straight blond hair and small pale frame, attracted even more suspicious glances when he was out with Peter.

Which was why Peter didn’t feel surprised when the lady who saw them walk out of the restaurant called the police. It only took minutes for them to verify Peter was Johnny’s guardian, but the event left the boy shaken.

Peter explained to him that this kind of thing was liable to occur, now and again, because he was black and Johnny was white.

It was something Peter and Anthony had already talked about.

After the killing of George Floyd in May, they had a long and emotive conversation about Black Lives Matter. Peter asked Anthony to make sure he had his mobile phone ready if the police stopped them.

“As a black man I have 10 seconds to explain who I am to the police before it potentially escalates,” Peter says.

“I always say to Anthony, ‘If the police stop me, please pull up the phone and record right away.’ Because I know he’s my only witness, you know? And I have 10 seconds to save my life.”

“I think he gets it. He knows that because we’re in America and I look different to him, I’m going to be treated differently.

“This kind of tension and suspicion is not something a white parent faces when they adopt a black child.”

According to Nicholas Zill, a research psychologist and a senior fellow for the Institute for Family Studies, white families in the US are much more likely than black families to adopt outside their race.

The latest available data, from 2016, show that only 1% of adoptions by black families were of white children – in 92% of cases they adopted black children. By contrast, 11% of adoptions by white families were of multiracial children, and 5% were of black children, Zill says.

“Currently it is still very rare to see black families adopting white children, much more so than the other way round and that may have to do with cultural biases that still exist within the US adoption system.”

Last year British couple Sandeep and Reena Mander won approximately £120,000 in damages after a judge ruled they had been discriminated against by not being allowed to adopt a non-Asian origin child.

The couple said they had been told by the local adoption service to research adopting a child from India or Pakistan, and sued the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, in a case backed by the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

“The law in the UK is very clear that race should not be a deciding factor in placing children,” says Nick Hodson, partner at McAlister Family Law firm, who has been specialising in law relating to children for over 20 years.

“The Children and Families Act of 2014 removed the requirement for local councils to give due consideration to children’s racial and cultural background when matching them with adopters. This was because historically BAME children were waiting much longer to be matched than white children.”

More consideration is now given to the individual needs of the child, he says. But he he accepts it’s possible that BAME parents, like the Manders, are still having difficulties.

“There may well be a disconnect with what the law says and what is happening on the ground,” he says.

Peter says that while he has not struggled as a black carer within the North Carolina fostering system, adopting Anthony may have been easier than usual because of his age. Nicholas Zill adds that after the age of five, it is harder to place children in a permanent home.

Peter knows of other black families who were made to wait a long time because a child of the same race was not available.

“We don’t live in an equal society,” he says, “but I want to be visible to break down stereotypes. There are stereotypes of black men as absent fathers, as criminals, all this plays a part. So that is why I have been open about my parenting, and regularly post photos of me and the boys on Facebook and Instagram.”

He’s gained almost 100,000 followers on Instagram by documenting their day-to-day life – under the name Fosterdadflipper – and been featured on ABC’s Good Morning America.

Peter has plans for the children after travel restrictions ease. He wants to take them to Uganda so they can see where their dad came from. He wants to build a relationship with Johnny’s family so that the boy’s transition back to his home is not a painful one. But despite some offers on his Instagram DMs, he has no desire to start a romantic relationship.

“My boys haven’t had stable male figures in their life,” Peter says. “They need me all to themselves right now, and so long as they do, I’ll be there for them completely.”

Johnny’s name has been changed to respect the wishes of his biological family.