Many Nigerians live in constant fear of being kidnapped and held for ransom by armed gangs, especially in the north-west of the country, where thousands of people have had to flee their homes. The insecurity means many in the region, which has the country’s largest number of registered voters, may not take part in the 25 February elections.

An unpaved mile-long road that ends at a tree stump is the only way for vehicles to get into Bakiyawwa village in Nigeria’s northern Katsina state.

This community of mostly subsistence farmers is not where you would expect criminals behind Nigeria’s lucrative kidnap-for-ransom business to go looking for victims.

It came as a surprise therefore when motorcycle-riding armed men invaded last September and abducted 57 villagers.

“They held my wife for 38 days,” said Abduljabara Mohammed, a civil servant and one of those considered well-off. He paid 1m naira ($2,100; £1,700) for her release.

“I gave them all my money and a motorcycle, then pleaded with them not to take me,” said Zaradeen Musa, 30, whose door was kicked in around 01:00 as the armed men, commonly referred to as bandits, operated unchallenged for four hours after repelling a police unit called in by the villagers.

Maria Sani, 45, was seized but managed to slip away as the bandits led the victims to their forest hideout.

She was left wondering what would have become of her if she had not escaped as, like many abducted that day, she could never have afforded the ransom.

All those kidnapped were eventually freed but only after months of negotiations that resulted in them paying with cash or valuables such as motorcycles. The abductions show how far the kidnapping problem has spread – not even the poorest are spared.

Nevertheless, those in Bakiyawwa would consider themselves lucky as the attacks sometimes turn deadly, such as the reported killing of more than 100 villagers by armed men last Friday in another part of Katsina.

Such armed groups in the north-west and violent secessionists in the south-east pose real threats to the 25 February elections, analysts say.

Attacks on offices of the Independent National Electoral Commission (Inec) led to polls being moved by a week in 2019, and the recent burning of an Inec office in the south-east has led to fears of another postponement, although officials have said there will be no delays.

In December, Inec announced that it was too dangerous to hold the polls in some parts of Katsina state but it is not clear what will happen on election day.

Law professor Chidi Odinkalu argues that this election risks being dragged into uncharted legal territory if insecurity hampers voting and a candidate believes they have been robbed of vital support.

In the past, people have stayed away from voting over fears of violence in southern states like Imo, Anambra, Lagos and Rivers, but now, the kidnap crisis in the north has left many disinterested in the elections.

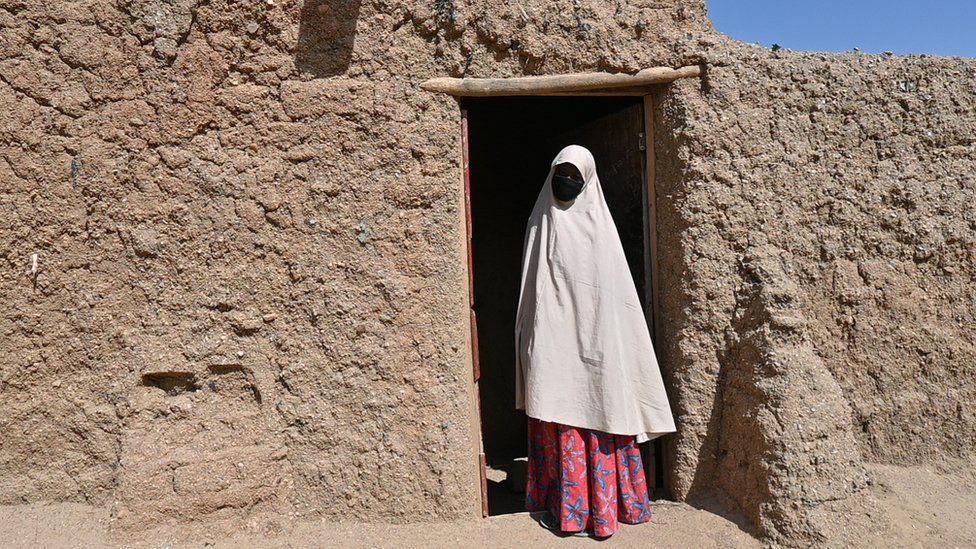

“You let kidnappers take me, now you want my vote,” said Mrs Sani through an interpreter.

Like many here she previously voted for President Muhammadu Buhari but she is sitting this one out.

President Buhari is standing down after serving two terms and Bola Tinubu is standing for the governing All Progressives Congress (APC).

“How can you see all the suffering and still vote for the APC?” said Lawal Suleiman, a former party member but now a lone voice in the village campaigning for the Labour Party’s Peter Obi.

Many others in Bakiyawwa say they would probably back the main opposition Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), if they vote at all.

“If Buhari couldn’t solve the problems of this country, no-one else can,” Nana Samaila, who fled her village in Batsari three years ago after attacks by armed groups, told the BBC.

Her daughter, Aisha Mama, also recently fled with her husband from the village of Dangyya after persistent night-time attacks forced her family to sleep in their farm for weeks.

Mrs Samaila had high hopes that President Buhari, a former military ruler who comes from Katsina, would solve Nigeria’s myriad issues when she first voted for him in 2003, but like many others, she is now disillusioned by the failures of his government.

Hundreds of school children have been abducted and released, and the state governor once asked residents to arm themselves against the bandits in a show of helplessness.

The leading candidates in the election recognise that insecurity, which is intertwined with rising food prices that have caused record levels of inflation, is Nigeria’s biggest challenge at the moment.

Atiku Abubakar of the PDP, Mr Tinubu of the APC and Mr Obi of the Labour Party are proposing police reforms, revamping the military and improved welfare, among other ideas.

Their plans are not radically different from what President Buhari, who was elected on a promise of tackling Islamist groups in the north-east, has done with only limited little success.

While he has largely succeeded in containing the Islamist insurgency, violence in the north-west and south-east has massively increased on his watch.

“He scattered [destroyed] the economy, there is so much insecurity,” said Mohammed Yusuf, a farmer originally from Katsina now forced into selling tea and cooked noodles on the streets of the region’s biggest city, Kano.

Kano, Katsina and Kaduna, dubbed the three Ks, are considered key states for whoever wants to emerge as Nigeria’s president because of their large voting population. There are more registered voters here than in the five south-eastern states.

Mr Buhari’s bloc of votes in the trio of states helped him win two elections in a row, and while some will still back the APC, there is a feeling that the party has lost ground in a region battered by insecurity.

Just two weeks ago, this was illustrated when stones were thrown at the president’s helicopter during a visit to Kano.

There is also a dark horse in the form of Rabiu Kwankwaso of the New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP). Only his die-hard supporters expect him to win the presidency, but he has emerged as a major disruptor who might decide who becomes the next president.

A former governor of Kano state and one-time defence minister, Mr Kwankwaso is immensely popular in Kano and neighbouring Jigawa state.

If he takes the majority of votes in Kano, whose six million registered voters rank second only to Lagos, it will greatly affect other candidates, especially those of the APC and PDP.

This might work in favour of the Labour Party which does not have a strong support base in the region.

Mr Kwankwaso, like many other Nigerian politicians, has switched parties several times. Last time, he backed the PDP and there are rumours he will step down for its candidate and fellow northerner, Mr Abubakar, at some point.

“He and Obi won’t win, though they are better alternatives to Mr Abubakar who is a crony capitalist,” said Umar Yahaya, a university student driving a taxi in nearby Kaduna.

“But anyone that votes the APC is rewarding them for failure,” he said, as we headed to the recently reopened Rigasa station to board the Kaduna-Abuja train. The line had been shut for months after a deadly attack by militants which saw the killing and abduction of dozens of passengers.

When Mr Buhari inaugurated the line in 2016 it was considered a sign of progress in the north, but now it has become a symbol of the violence consuming the region.