Amoako Boafo, who has become a superstar in the art world, has moved back home to Ghana, where one of his self-portraits is being exhibited. He told journalist Stephen Smith that he never intended to be an artist.

For all Amoako Boafo’s head-turning success, he is a reluctant interviewee. Not yet 40, he has had his canvases displayed in the galleries of the mega-dealer Larry Gagosian, who has hailed him as “the future of portraiture”.

Boafo says he used to vie with his friends to see who could do the best drawings of their favourite superheroes, but art simply wasn’t a career choice when he was growing up.

“All I know is that studying portraiture growing up, it never dawned on me that it was a form of art that artists of colour could reference and study,” he says of Gagosian’s high praise. “So to see that my work is regarded in that way, is a lot to process.

His is a real-life rags to riches story. The Ghanaian started from humble beginnings in his hometown of Accra and had to help support his mother. Now his portraits of black subjects, often painted with his fingertips, can command up to seven figures at auction.

He has emblazoned his work on to the fuselage of Jeff Bezos’s rocket ship, becoming one of the first artists to exhibit in space. It doesn’t come more ragged, it doesn’t get much richer.

Boafo’s the shooting star of a remarkable constellation of talent from West Africa. One of the striking features of this scene is how readily Boafo and his peers acknowledge each other’s ability and pool their resources and knowhow.

Returning to his home in Accra from international travel, he was in his studio to check on the progress of an artists’ residency he supports. He was also exhibiting at a group show in the Ghanaian capital.

It was a rare opportunity to catch up with a man who is often abroad working on commissions, and perhaps a chance to grab a few words with him.

He was born in 1984 and his father died when he was very young. His mother worked as a cook and Boafo taught himself to paint while she was out of the house.

He showed promise on the tennis court and supported himself for a few years as a semi-pro player. He only got the chance to go to art school after one of the people his mum worked for offered to pay his tuition fees.

He graduated top of his class from the Ghanatta College of Art and Design in Accra in 2008, taking the title of Best Portrait Painter of the Year.

In 2014, he moved to Europe with an Austrian artist called Sunanda Mesquita, who became his wife.

Boafo’s big break came in 2018 when his paintings were discovered on Instagram by Kehinde Wiley, the artist best known for his portrait of former US President Barack Obama, who recommended Boafo to the galleries he works with.

I asked him about getting Wiley’s backing.

“It was a major step for me,” he replied. “His support came in the early days of my career, and this partly inspired my desire to continue to form relationships and share spaces with my fellow artists and creatives for the purpose of sharing experiences which would hopefully be beneficial to them.”

I met Boafo at his studio close to the seafront, dot.ateliers, a three-storey building designed by the well-known Ghanaian-British architect Sir David Adjaye.

The building is the colour of sand and finished in uncompromising breezeblock. This ramification wraps around an inner structure, enabling cooling winds off the sea to ventilate the property. A staircase winding inside the breezeblock and up to Boafo’s workspace on the third floor offers a view of crashing surf and of a funeral taking place in a nearby compound, the mourners in vivid designs of black and white.

The roof of Boafo’s building is a cockscomb with three points, said to be an audacious nod to the crown motif in the paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

In the space of a very few years, Boafo has gone from selling his pictures for £100 ($125) or so in Ghana to exhibiting at international fairs and seeing buyers outbid each other for his work.

In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement, museums and collectors belatedly realised that they had few if any works by black artists in their holdings and scrambled to make good the omission.

Work of Boafo’s calibre has been particularly in demand.

He says he’s flattered by the accolades. I wondered if his rapid ascent had brought its own pressures.

“My success, hopefully, has allowed me to impact the lives of others in my community.

“Being able to provide resources for members in my creative community through my residency means a lot to me. As far as stress of reaching a wider audience, I can’t say it’s that heavy.”

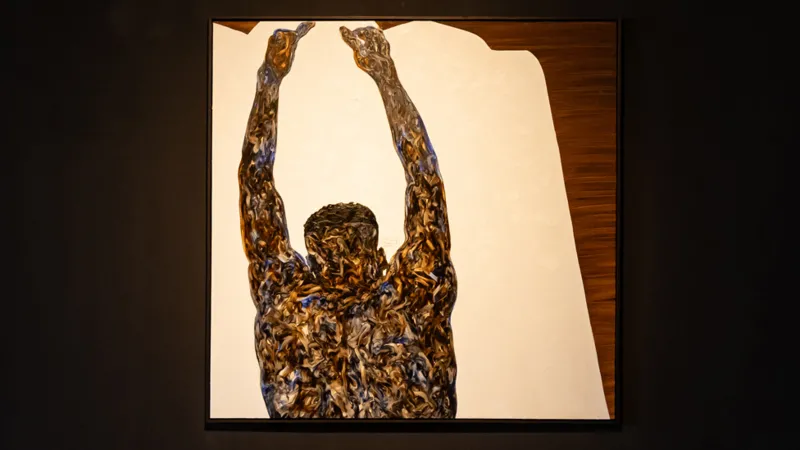

Boafo has contributed a self-portrait to an exhibition of work by artists from the African diaspora – In and Out of Time – which is on show at Gallery 1957 in Accra, curated by Ekow Eshun, a former director of the ICA in London.

In his painting, the artist is seen from the back, naked from the waist up, arms above his head.

As is often his practice, he had painted the work with his fingertips. He signed it “Amoako Boafo King”. A source close to the exhibition told me that King is a name he uses, or perhaps the meaning of his name.

The gallery is owned by Marwan Zahkem, a Lebanese-born developer and art impresario, who was one of the first people to buy Boafo’s work and exhibit it.

“What we are seeing in West Africa now is a movement like the Young British Artists in the 1980s, and Amoako is the Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin of this movement,” he told me.

Osei Bonsu, a curator of international art at London’s Tate Modern, put Boafo on the cover of his major new book African Art Now – or rather, he chose Boafo’s painting Yellow Dress, which sold at Christies last year for £675,000, more than double its estimate. The record price for Boafo’s work is currently £2.5m.

“In chronicling a generation of young people who perform their identities through the medium of the ‘selfie’, Boafo’s portraits figure a vital relationship between the historical traditions of portraiture and the social media age we are living in today,” Bonsu said.

As for the superstar himself, Boafo told me that he much prefers painting to talking about painting.

“At the end of the day, I paint because I love to create,” he said.

“As an artist, I think we are most stressed when we have to attend to tasks that pull us away from the studio. So for me activities which are not painting, I won’t say I’m stressed about, but are less exciting – unless it’s tennis!”