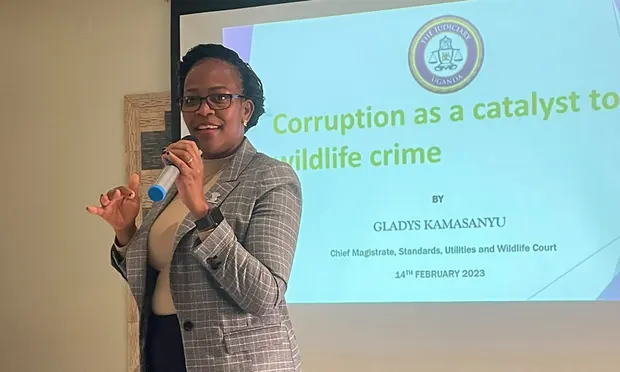

Having tried more than 1,000 wildlife crime cases, Gladys Kamasanyu is changing attitudes to animal rights and the ‘cruel’ trade in rhino horns, pangolins and ivory.

When Gladys Kamasanyu was asked to become head of a new wildlife court in Uganda in 2017, she felt conflicted. Although the chief magistrate had participated in discussions that led to the court’s creation – the first in Africa dedicated to wildlife crime – part of her wanted to stay with the human cases she had always adjudicated on rather than swap the familiar for the risk of the unknown.

Kamasanyu has tried more than 1,000 wildlife cases, convicting more than 600 traffickers, including a man sentenced to life in prison last year for possession of ivory. She has presided over cases involving pangolins, the most trafficked mammal in the world, and ruled on cases involving rhino horns, elephant ivory and hippopotamuses’ teeth.

“Kamasanyu has lifted the bar for wildlife adjudication in Uganda, if not the region,” says Edward Anyoli, a court reporter in Kampala. “She’s in court Monday to Friday, hearing cases and evidence or writing judgments. Her court might be the only one in the country without a backlog.”

Two years ago, on UN Wildlife Day, the Ugandan Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Antiquities presented Kamasanyu with an award for her contribution to Ugandan conservation.

“Kamasanyu gives rulings on sophisticated wildlife criminals,” says Barirega Akankwasah, director of Uganda’s environmental agency. “She isn’t afraid to sentence them, even when it puts her in danger.”

Her example has sent a strong message to poachers. For years, criminals used Uganda as a conduit for trafficking wildlife products from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan. Now they think twice before they commit wildlife crime here, says Akankwasah.

“[Before we started] the justice system prioritised other cases,” says Kamasanyu. “But our animals were dying, some of our species were going extinct. I’m playing my part to reverse this.”

Her stern rulings have led some to suggest that the chief magistrate prefers animals to humans. She denies that: “I love animals just the way I love life and humanity.”

Born in south-west Uganda, Kamasanyu grew up around animals – she is the proud owner of a nine-year-old chicken called Kisakye (“her mercy”) – but she never imagined wildlife would feature in her career plans.

In 2021, she threw herself into learning about wildlife, biodiversity and the environment, studying animal law at the Lewis & Clark law school in the US city of Portland. But it was not until she presided over cases, hearing graphic testimonies of how poachers killed animals, that she decided to commit herself to fight for wildlife “as long as I shall live”.

“You can’t imagine the cruelty poachers subject these animals to,” says Kamasanyu. “They trap them, shoot them, poison them; they chase them all day.”

Kamasanyu says all her cases are special but some are unique, including the poacher she sentenced to life imprisonment. “He was a repeat offender. He had been tried, convicted and sentenced to 18 months in prison in 2017. What does he do when he gets out? He’s arrested again with the same ivory and okapi skin in the same area.

“I speak for the animals. I speak for those non-humans who cannot speak. If I don’t speak loudly, I’m not doing a good job.”

Kamasanyu founded Help African Animals, an organisation that trains prosecutors and investigators of wildlife crime and animal rights. “There is a lot of ignorance in our society,” she says.

“Many people think animals are [their] property and that they can go to forests and hunt them every day. They think these animals give birth every day and that they will always be there.”

The magistrate regrets that by the time poachers are caught, it is too late for the animal. “I’m frustrated whenever the prosecution fumbles a case and I have to dismiss it,” she says.

She is also unhappy that law enforcement agencies continue to miss the big players behind wildlife crime. “We are arresting the smaller players down the line who poach because they have been promised 5,000 shillings [£1] for every animal. But we miss the kingpins who send them.” She points to a 2019 case involving a Vietnamese gang arrested with almost four tonnes of ivory and pangolin scales, who fled the country after securing bail.

Despite this, Kamasanyu hopes she can make a difference: “People have to understand that animals aren’t property, and that they won’t always be here if we don’t protect them.”