As the BlacKkKlansman film-maker picks up the British Film Institute’s top honour, he talks about being accused of provoking race riots, why his Malcolm X biopic will endure – and the problem with awards

‘When I was little,” says Spike Lee, “my father hated Hollywood films, but my mother was a cinephile. And since I was the eldest sibling, I was her movie date. She loved James Bond and took me to see Goldfinger. The theatre was packed. Those Bond films have explosions and shootings, but there was a lull in the action and everything was quiet. I said: ‘Mommy, why is that lady named Pussy Galore?’ And the whole audience heard me. My mother grabbed me by the neck and said: ‘Don’t say another word!’” Lee cackles, clearly tickled. “She was so embarrassed.” He pauses. “Pussy Galore,” he repeats, laughing.

Although the film-maker’s grasp of cinema has come a long way since then, there is still something in him reminiscent of that six-year-old boy: curious, unafraid to speak his mind, keen to ask awkward questions. After a career spanning more than 30 years, the 65-year-old has developed a reputation as Hollywood’s conscience. His films have chronicled black lives and challenged assumptions about race, class and gender; in interviews and speeches, he has thundered against social injustice, police brutality and the entertainment industry’s problems with representation.

For all of this and more, Lee was this week awarded the BFI Fellowship, the highest honour bestowed by the British Film Institute to individuals for their “outstanding contribution to film or television culture”. Previous recipients have included Orson Welles, Laurence Olivier, Elizabeth Taylor and Steve McQueen. “One person might accept an award,” says Lee, speaking from Los Angeles, “but a lot of people were responsible that you don’t see. This fellowship is for all the people that have helped me. Not just people in the industry, but my parents, siblings, teachers, not to forget my beautiful wife Tonya.”

With race, it’s always two steps forward, one step back. But I’ll never say there’s been no progress. The struggle continues

There isn’t room to list all of Lee’s work. Since the 1986 Cannes premiere of She’s Gotta Have It, a radical sex comedy about an African American woman and her three male suitors, shot in two weeks for $175,000, he has made dozens of films. Highlights include 1989’s Do the Right Thing, which explored racial tensions in Brooklyn, and 2018’s BlacKkKlansman, the true story of a black detective who went undercover with the Ku Klux Klan. In between came Inside Man, a thriller about a Wall Street heist, and 4 Little Girls, a documentary about the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

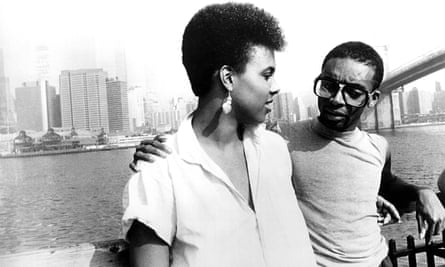

But perhaps his most renowned work is Malcolm X, his 1992 biopic of the African American activist, starring Denzel Washington and Angela Bassett. The film, which is being reissued on a new 35mm print in liaison with the BFI National Archive this summer, opens with grainy footage of Rodney King being beaten by Los Angeles police in 1991, set against Washington delivering the Malcolm X speech I Charge the White Man. How relevant does Lee think it is today?

“Very relevant. Did you see what happened in Memphis recently?” says Lee, referring to the killing of Tyre Nichols, a shocking reminder that history has a habit of repeating itself. “Malcolm X will stand the test of time. And that performance by Denzel still amazes me. It’s one of the greatest I’ve ever seen.” As for the fight against racism, he adds: “It’s always two steps forward, one step back. But I’ll never say there’s been no progress. The struggle continues.”

I’ve misspoken many times in my life. And when Black Twitter gets on your ass, they get on your ass.

Malcolm X was once again being hotly debated only last week after Daniel Scheinert, one of the directors of Everything Everywhere All at Once, called it his favourite “crime movie”. Lee seems nonplussed, even amused. “I’d never heard that description before,” he laughs. “But look, I’m not going to kill the guy. I’ve misspoken many times in my life, too. So I’m calling on Black Twitter to give the guy a break – because when Black Twitter gets on your ass, they get on your ass.”

It’s a surprisingly magnanimous stance from an auteur who’s never pulled his punches, having previously entangled with the likes of Donald Trump (who complained about Lee’s “racist hit on your president” 2019 Oscars speech), Quentin Tarantino (for the excessive use of the N-word in his films), Clint Eastwood (for the absence of African American soldiers in Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima), and black director Tyler Perry (for the “buffoonery” of his Madea franchise).

This is the kind of toughness his late mother perceived in him when she nicknamed him Spike. Lee was born Shelton Jackson Lee in Atlanta, Georgia, but raised in what he calls “the Republic of Brooklyn”. His mother was a teacher of arts and black literature, while his father is a jazz musician. He went to Morehouse, a historically black college in Atlanta that counts Martin Luther King Jr and Samuel L Jackson among its alumni, and later New York University (NYU) graduate film school.

Within his first few weeks at NYU, Lee became a voice of dissent, taking issue with his class being shown The Birth of a Nation, DW Griffith’s 1915 epic, notorious for glorifying the Ku Klux Klan. They were taught about the film’s technical innovations, with no mention of it being a recruiting tool for the Klan. In response, he made a student film called The Answer, in which a young black director is hired by a Hollywood studio to remake The Birth of a Nation. When his vision is compromised by the studio, the director pulls out and is attacked by Klan members who place a burning cross in front of his house. Some NYU faculty members found the film so offensive that they recommended (unsuccessfully) that Lee not be invited back for his final two years.

The incident foreshadowed the complicated, and at times fraught, relationship between Lee and the film industry. Lee has received numerous accolades including an Oscar, two Emmys and a Bafta – as well as plenty of castigation. “People forget that when Do the Right Thing came out, critics with loud voices said: ‘This film will incite African Americans to riot all across the country.’ It sounds crazy now, but that was written by prominent film critics, that my film would cause black folks to run amok. They’ve still never said they fucked up. It was a very racist take on a film that dealt with the legacy of racism in the US.”

Then there’s been the constant battle with the Academy Awards. In 1990, the feelgood race-relations film Driving Miss Daisy won best picture over Do the Right Thing while Do The Right Thing wasn’t even nominated in the category, causing much controversy. (It was nominated in two other categories.) Three decades later, in 2019, BlacKkKlansman was beaten to best picture by Green Book, which reportedly led to Lee waving his arms in disgust and appearing to storm out. (BlacKkKlansman did win an Oscar, though, for best adapted screenplay.)

A few months after Lee was awarded an honorary lifetime achievement Oscar, the director became one of the leading figures of the #OscarsSoWhite campaign and the 2016 boycott of the Academy Awards, after the second consecutive year in which no people of colour were nominated in any acting category.

While there have been advances, criticism resurfaced this year when no black women were nominated for best actress. Although strongly tipped, both Viola Davis (The Woman King) and Danielle Deadwyler (Till) were overlooked, while Britain’s Andrea Riseborough was included for her performance in low-budget drama To Leslie after a last-minute campaign from celebrities. The Academy reviewed and later upheld Riseborough’s nomination after a backlash.

“You know, I’ve really got nothing to say about it,” Lee replies when asked about the nominations. “I’m happy Angela Bassett got nominated. I’m happy Ruth Carter – who for a long time was my costume designer – got nominated.” But beyond that, he remains tight-lipped. “It gets tricky when you get these award things. And the Academy has a history with …” He hesitates. “The Academy has a history, let’s leave it at that. But the whole #OscarsSoWhite hashtag definitely made an impact. The Academy, to their credit, made changes to bring diversity to the voting body.”

No disrespect to Harry Styles but Beyoncé has been nominated for the album of the year Grammy four times and not won? That’s straight-up bullshit

He’s more forthcoming about the recent Grammy awards – in particular Beyoncé losing out in the best album category. “I’m not the male president of the Bey Hive [Beyoncé’s fanbase], but I love and support Beyoncé. Her album is amazing. I know she’s won multiple Grammys, but four times nominated for album of the year and she’s lost every time? No disrespect to those artists like Adele or Harry Styles who won. It’s not their fault, but that’s some straight-up bullshit.

“There’s a history of great black artists who come up for these awards and don’t win. We all know their work is great, because art speaks for itself. But then it always comes down to this tricky territory of validation. Do black artists say: ‘Fuck it’ – or seek white validation and chase awards? I just want to give a shoutout to my sister Beyoncé. We know what the deal is. It’s straight-up shenanigans, skulduggery, subterfuge. Or as the British say: it’s some poppycock!”

How difficult is it for artists to speak out? “It depends who you’re talking about,” he says. “I’ve learned that you have to speak truth to power. When I take my last breath, which won’t be soon by the way, it’ll be written that I was on the right side of history. But it’s an individual choice. There’s certain times when you know there’ll be repercussions and you’ve got to make a choice to speak out or clam up.”

But speaking truth to power, he adds, has never felt like a burden. “Because I’ve never tried to position myself as speaking for 45 million African Americans. I always say, ‘This is my opinion’. Fairly early on, my late mother said: ‘Spike, we as black people are not one monolithic group. We don’t look alike, talk alike, think alike. We’re very diverse, from many different backgrounds.’ And I took that to heart.”

Nevertheless, Lee has become a leading cultural figure in his own right. Four of his films are preserved in the US National Film Registry for being culturally and historically significant. He’s made music videos for the likes of Public Enemy, Stevie Wonder and Prince, and adverts with Michael Jordan for Nike. Barack and Michelle Obama’s first date was to see Do the Right Thing. He even managed to get the then newly released Nelson Mandela to make a cameo in Malcolm X.

Lee, who is also a tenured professor at NYU, recently entered into a partnership with Netflix that will see him directing and producing narrative features. As part of his visit to the BFI – a trip he has scheduled around Arsenal’s home game against Manchester City – he will be teaching students a masterclass. When I ask him what his one tip for young film-makers is, the answer is fairly simple: “Bust your ass.”