Rome’s city council voted earlier this month to name a future metro station in the Italian capital in honour of Giorgio Marincola, an Italian-Somali who was a member of the Italian resistance.

He was killed at the age of 21 by withdrawing Nazi troops who opened fire at a checkpoint on 4 May 1945, two days after Germany had officially surrendered in Italy at the end of World War Two.

The station, which is currently under construction, was going to be called Amba Aradam-Ipponio – a reference to an Italian campaign in Ethiopia in 1936 when fascist forces brutally unleashed chemical weapons and committed war crimes at the infamous Battle of Amba Aradam.

The name change came after a campaign was launched in June, in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests around the world following the killing of African American George Floyd by US police.

Started by journalist Massimiliano Coccia, he was supported by Black Lives Matter activists, other journalists and Italian-Somali writer Igiabo Scego and Marincola’s nephew, the author Antar Marincola.

The ‘black partisan’

Activists first placed a banner at the metro site stating that no station should be named after “oppression” and pushed for Marincola’s short, but remarkable life to be remembered.

He is known as the “partigiano neroor” or “black partisan” and was an active member of the resistance.

In 1953 he was posthumously awarded Italy’s highest military honour, the Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare, in recognition of his efforts and the ultimate sacrifice he made.

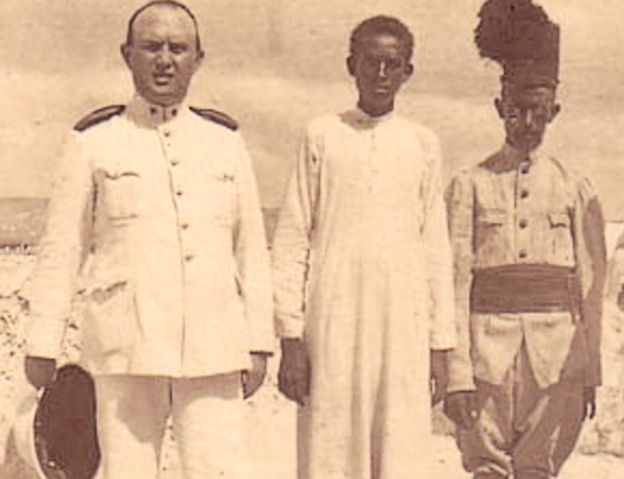

Marincola was born in 1923 in Mahaday, a town on the Shebelle River, north of Mogadishu, in what was then known as Italian Somaliland.

His mother, Ashkiro Hassan, was Somali and his father an Italian military officer called Giuseppe Marincola.

At the time few Italian colonists acknowledged children born of their unions with Somali women.

But Giuseppe Marincola bucked the trend and later brought his son and daughter, Isabella, to Italy to be raised by his family.

Isabella went on to become an actress, notably appearing in Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice), released in 1949.

Giorgio Marincola too was gifted, excelling at school in Rome and went on to enrol as a medical student.

During his studies he came to be inspired by anti-fascist ideology. He decided to enlist in the resistance in 1943 – at a time his country of birth was still under Italian rule.

He proved a brave fighter, was parachuted into enemy territory and was wounded. At one time he was captured by the SS, who wanted him to speak against the partisans on their radio station. On air he reportedly defied them, saying: “Homeland means freedom and justice for the peoples of the world. This is why I fight the oppressors.”

The broadcast was interrupted – and sounds of a beating could be heard.

‘Collective amnesia’

But anti-racism activists want far more than just the renaming of a metro stop after Marincola – they want to shine the spotlight on Italy’s colonial history.

They want the authorities in Rome to go further and begin a process of decolonising the city.

This happened unilaterally in Milan when, amid the Black Lives Matter protests, the statue of controversial journalist Indro Montanelli, who defended colonialism and admitted to marrying a 12-year-old Eritrean girl during his army service in the 1930s, was defaced.

Yet to bring about true change there needs to be an awareness about the past.

The trouble at the moment is what seems to be a collective amnesia in Italy over its colonial history.

In the years I have spent reporting from the country I am always struck at how little most Italians seem to know about their colonial history, whether I’m in Rome, Palermo or Venice.

The extent of Italy’s involvement in Eritrea, Somalia, Libya and Albania to Benito Mussolini’s fascist occupation of Ethiopia in the 1930s is not acknowledged.

Somali bolognese

Last month, Somalia celebrated its 60th anniversary of independence.

Reshaped by 30 years of conflict, memories of colonial times have all been lost – except in the kitchen where a staple of Somali cuisine is “suugo suqaar”- a sauce eaten with “baasto” or pasta.

But for this Somali bolognese, we use cubed beef, goat or lamb with our version of the classic Italian soffritto – sautéed carrots, onion and peppers – to which we add heady spices.

I love to cook these dishes and last summer while I was in Palermo did so for Italian friends, serving it with shigni, a spicy hot sauce, and bananas.

It was a strange pairing for Italians, though my friends tucked in with gusto – with only the odd raised eyebrow.

And Somalis have also left their own imprint in Italy – not just through the Marincola siblings – but in the literature, film and sports.

Cristina Ali Farah is a well-known novelist, Amin Nour is an actor and director, Zahra Bani represented Italy as a javelin thrower and Omar Degan is a respected architect.

And today Somalis constitute both some of Italy’s oldest and newest migrants.

In spring 2015 I spent a warm afternoon meandering throughout the backstreets near Rome’s Termini station meeting Somalis who had been in Italy for decades and Somalis who had arrived on dinghies from Libya.

Those new to Italy called the older community “mezze-lira” – meaning “half lira” to denote their dual Somali-Italian identities.

In turn they are called “Titanics” by established Somalis, a reference to the hard times most migrants have faced in making the perilous journey across the Mediterranean to reach Europe, and the lives they will face in Italy with the political rise of anti-migration parties.

The naming of a station after Marincola is an important move for all of them – and a timely reminder for all Italians of the long ties between Italy and Somalia.