Regina Twala was an influential writer and political activist of the 50s and 60s. Yet while European men gained acclaim from her work, her name was almost erased from memory.

Over the course of 2018, during a research period in the small southern African kingdom of Eswatini, I made multiple phone calls. My question was always the same: had the person heard of someone called Regina Twala?

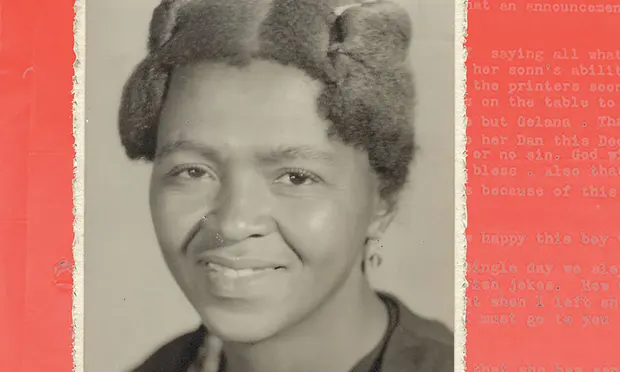

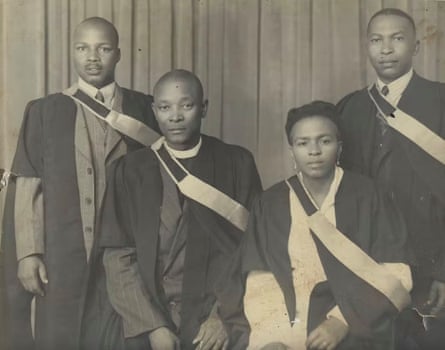

Twala had been a writer, intellectual and anti-colonial political activist of the 1950s and 60s. She was born in South Africa, but after her arrest in 1952 for participating in the non-violent resistance movement the Defiance Campaign, she found the country increasingly repressive. In 1954, like many other Black activists she chose to cross the border to Eswatini, formerly Swaziland, to live in exile, and died there in 1968 at 60. She was the second Black woman to obtain a degree from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and was one of the co-founders of the Swaziland Progressive Party, Eswatini’s first political party, in 1960.

Yet no one I phoned had heard of Twala. I was surprised. From the little I knew of her, Twala had clearly been an influential figure. And Eswatini – where I was raised and educated – is a small country, about the size of New Jersey. It’s hard to remain anonymous there.

How could I make sense of the fact that a significant woman of her era could be virtually erased from popular history and memory? At the heart of the mystery stood another intellectual – a celebrated European historian called Bengt Sundkler. As I would learn, Sundkler’s fame existed in direct reciprocity with Twala’s obscurity.

In 1976, Sundkler published a book on religion in Africa, called Zulu Zion. It would become a celebrated reference point for all interested in how Christianity in Africa expressed itself via existing indigenous religious beliefs.

Unable to travel to southern Africa due to his heavy teaching obligations at Uppsala university in Sweden, Sundkler hired Twala as his research assistant, paying her to undertake an investigation of African churches throughout the 1950s. The Uppsala archives contain dozens of pages of research material sent by Twala to Sundkler on this topic. Consider this paragraph, where Twala describes how a group of church women danced with flags and sticks to the royal palace (Lobamba) of the king of Swaziland, Sobhuza II:

“A bell was rung, and that was a signal for all to find their staves and set out for Lobamba [Sobhuza’s palace], then when the women began singing the congregation began marching in circles. The women with flags, emagosa, always led the way. This parade before the Church House is called kuhlehla, same term as used for warriors or age-groups when they dance or give a display before royalty.”

Imagine my astonishment when I discovered a strikingly similar passage published in Sundkler’s Zulu Zion. Sundkler passed these words off as his own but they were lifted near-directly from the material Twala had sent him 20 years earlier:

“A bell was rung, the signal for all to find their “holy sticks” and to set out for Lobamba. The lady wardens (emagosa) bore flags and led the way. The women with sticks, while marching, would walk in circles, kuhlehla. This was the term used for warriors or age-groups when giving a dancing display before royalty.”

Despite Sundkler’s plagiarism of Twala’s work, his book barely mentions her (by the time it was published, Twala had been dead for a decade, and her name forgotten by all except her family). Sundkler’s preface to Zulu Zion briefly referenced “the late Mrs Regina Twala [who] established many contacts which I could not have made on my own”. But that is all.

Sundkler reduced Twala to a researcher-fixer who procured contacts for him, rather than a co-researcher in her own right. Sundkler certainly didn’t identify Twala as the author of the words he was passing off as his own.

Omitting to properly acknowledge his research assistants was something Sundkler had a habit of doing, including with his previous book, Bantu Prophets in South Africa (widely hailed as a foundational text in the history of religion in Africa upon publication in 1948). Doubtless, this was a common academic practice of this period, an era during which our contemporary sensibilities regarding research ethics were largely absent.

In colonial southern Africa, the white literary establishment had little time for an unknown Black female writer

At the same time, at least one South African scholar of the 1950s had criticised Sundkler for failing to acknowledge the work done for him by Black researchers. Appropriation of others’ work was a point Sundkler would have been sensitive about. He even writes in Zulu Zion of his own “anticipation of the study to be made one day by an African scholar living much closer to the anguish and jubilation of the movement than [he] ever could be”. Seemingly, it did not cross his mind that one African scholar had already conducted a study, right under his very nose – and that was Regina Twala. For Sundkler, scholars were only legible if white and of equal social footing.

Yet Sundkler was not the only obstacle Regina Twala would face in her efforts to establish herself as a writer. Twala’s too-short life was a chronicle of struggling to assert her reputation and ensure her legacy. Her first novel, Kufa, written in 1939, was rejected by white-run presses in South Africa and remains unpublished; her articles were turned away by the editors of white literary magazines; her final magnum opus – a strikingly creative ethnography of gender in 1960s Eswatini – was spurned by university presses in the US.

It was only in 2018, 50 years after Twala’s death, that I discovered her unpublished writings folded into the archives of the European and North American academics whom she had done paid research for (including but not limited to Sundkler). Long forgotten, Twala’s legacy only lived on through the reputations of her more famous counterparts.

In the context of colonial rule in southern Africa, editors and publishers – the gatekeepers of the white intellectual-literary establishment – had little time for an unknown Black female writer. Success in publishing had everything to do with connections, who you knew, who knew you, and whether you counted as a member of the club.

This, then, is the untold story of scholarship, of the hidden realities behind the glossy published books that find their way on to the shelves of our libraries. We think of knowledge as floating in a realm detached from the messy business of everyday life. In fact, mundane realities of race and gender shape what is counted as “knowledge”.

Certain scholars – usually white, usually male, often affiliated to prestigious universities and research institutions – are permitted to define our scholarly canons. It is their work that so often finds its way into the pages of renowned journals and books published by learned university presses.

Twala’s story reminds us of the forgotten people whose unacknowledged contributions so often lie beneath the work of these publicly acclaimed scholars. Her story points to the dirty secret of how books are often not written by those whose names they bear on their title pages. Sundkler’s fame was Twala’s erasure. The mystery as to how Twala – a brilliant woman of her times – was forgotten, lies with the public acclaim Sundkler received for words he did not write.