Sir Mo Farah was brought to the UK illegally as a child and forced to work as a domestic servant, he has revealed.

The Olympic star has told the BBC he was given the name Mohamed Farah by those who flew him over from Djibouti. His real name is Hussein Abdi Kahin.

He was flown over from the East African country aged nine by a woman he had never met, and then made to look after another family’s children, he says.

“For years I just kept blocking it out,” the Team GB athlete says.

“But you can only block it out for so long.”

The long-distance runner has previously said he came to the UK from Somalia with his parents as a refugee.

But in a documentary by the BBC and Red Bull Studios, seen by BBC News and airing on Wednesday, he says his parents have never been to the UK – his mother and two brothers live on their family farm in the breakaway state of Somaliland.

His father, Abdi, was killed by stray gunfire when Sir Mo was four years old, in civil violence in Somalia. Somaliland declared independence in 1991 but is not internationally recognised.

Sir Mo says he was about eight or nine years old when he was taken from home to stay with family in Djibouti. He was then flown over to the UK by a woman he had never met and wasn’t related to.

She told him he was being taken to Europe to live with relatives there – something he says he was “excited” about. “I’d never been on a plane before,” he says.

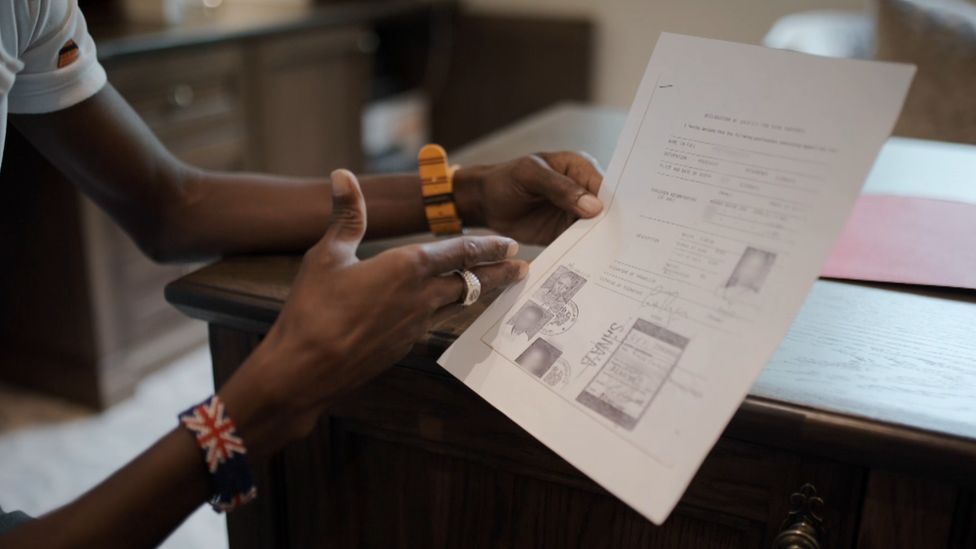

The woman told him to say his name was Mohamed. He says she had fake travel documents with her that showed his photo next to the name “Mohamed Farah”.

When they arrived in the UK, the woman took him to her flat in Hounslow, west London, and took a piece of paper off him that had his relatives’ contact details on.

“Right in front of me, she ripped it up and put it in the bin. At that moment, I knew I was in trouble,” he says.

Sir Mo says he had to do housework and childcare “if I wanted food in my mouth”. He says the woman told him: “If you ever want to see your family again, don’t say anything.”

“Often I would just lock myself in the bathroom and cry,” he says.

For the first few years the family didn’t allow him to go to school, but when he was about 12 he enrolled in Year 7 at Feltham Community College.

Staff were told Sir Mo was a refugee from Somalia.

His old form tutor Sarah Rennie tells the BBC he came to school “unkempt and uncared for”, that he spoke very little English and was an “emotionally and culturally alienated” child.

She says the people who said they were his parents didn’t attend any parents’ evenings.

Sir Mo’s PE teacher, Alan Watkinson, noticed a transformation in the young boy when he hit the athletics track.

“The only language he seemed to understand was the language of PE and sport,” he says.

Sir Mo says sport was a lifeline for him as “the only thing I could do to get away from this [living situation] was to get out and run”.

He eventually confided in Mr Watkinson about his true identity, his background, and the family he was being forced to work for.

‘The real Mo’

The PE teacher contacted social services and helped Sir Mo to be fostered by another Somali family.

“I still missed my real family, but from that moment everything got better,” Sir Mo says.

“I felt like a lot of stuff was lifted off my shoulders, and I felt like me. That’s when Mo came out – the real Mo.”

Sir Mo began making a name for himself as an athlete and aged 14 he was invited to compete for English schools at a race in Latvia – but he didn’t have any travel documents.

Mr Watkinson helped him apply for British citizenship under the name Mohamed Farah, which was granted in July 2000.

In the documentary, barrister Allan Briddock tells Sir Mo his nationality was technically “obtained by fraud or misrepresentations”.

Legally, the government can remove a person’s British nationality if their citizenship was obtained through fraud.

However, Mr Briddock explains the risk of this in Sir Mo’s case is low.

“Basically, the definition of trafficking is transportation for exploitative purposes,” he tells Sir Mo.

“In your case, you were obliged as a very small child yourself to look after small children and to be a domestic servant. And then you told the relevant authorities, ‘that is not my name’. All of those combine to lessen the risk that the Home Office will take away your nationality.”

A Home Office spokesperson told BBC News it will not take action over Sir Mo’s illegal entry to the UK.

It was shortly after this that a woman approached him in a Somali restaurant in London, and gave him a tape.

It contained a recorded message for Sir Mo, from someone he hadn’t heard from in a long time – his mum Aisha.

“It wasn’t just a tape,” Sir Mo says. “It was more of a voice, and then it was singing sad songs for me like poems or like traditional song, you know. And I would listen to it for days, weeks.”

The side of the tape had a phone number on it, asking him to call – but added, “if this is a bother or causing you trouble, don’t, just leave it – you don’t have to contact me”.

“I’m going, ‘Of course I want to contact you!'” Mo says.

The mother and son then had their first phone call.

It was shortly after this that a woman approached him in a Somali restaurant in London, and gave him a tape.

It contained a recorded message for Sir Mo, from someone he hadn’t heard from in a long time – his mum Aisha.

“It wasn’t just a tape,” Sir Mo says. “It was more of a voice, and then it was singing sad songs for me like poems or like traditional song, you know. And I would listen to it for days, weeks.”

The side of the tape had a phone number on it, asking him to call – but added, “if this is a bother or causing you trouble, don’t, just leave it – you don’t have to contact me”.

“I’m going, ‘Of course, I want to contact you!'” Mo says.

The mother and son then had their first phone call.