His death last year at 41 left a chasm in the industry. In a new BBC documentary, director Cassie Quarless explores the legacy of one of the most important – and controversial – designers of the 21st century

‘There is a whole generation of Black people who went and bought their first sewing machine because of Virgil,” says the fashion critic Bliss Foster. “He saw what was happening before anyone else,” adds the DJ and producer Honey Dijon. And yet, according to the activist Trinice McNally, “a lot of people hated him”.

Louis Vuitton director Virgil Abloh certainly left a chasm in the fashion industry when he died last year at just 41. Founder of the beloved brand Off-White – worn by everyone from the Kardashians to kids in Croydon – and creative director for Kanye West, Abloh was one of the most important designers of the 21st century.

In a new BBC documentary, Virgil Abloh: How to Be Both – directed by Generation Revolution’s Cassie Quarless and executive produced by Gabriel Jagger (son of Mick) and Janet Lee – the legacy of a Black pioneer is fully explored. It shows how Abloh rattled the zeitgeist, emphasising how hard it was until very recently for Black people to be taken seriously in the world of fashion, let alone to conquer it.

Take the 2009 Paris fashion week photo, which featured Abloh with his collaborator West and a crew of flamboyant eccentrics dressed as though they were thrown into a room crammed with random designer items and told they had 30 seconds to assemble outfits. Dressed in a blue puffer gilet, yellow trainers and red glasses, Abloh smirks knowingly at the camera – is it all a piss-take? – while West, wearing a plaid trenchcoat and holding a Goyard briefcase in his brown-leather-gloved hands, fixes us with a thousand-yard stare.

The image was roundly mocked. Black men wearing fashion in that way wasn’t embraced at the time, says the shot’s photographer, Tommy Ton. “Certain people looked at it as inspiring. Others could definitely eat their words now,” he adds. For the fashion writer Thom Bettridge, it was a “groundbreaking moment.”

Those moments kept on coming: a cuboid off-road Mercedes Jeep, then a retro-reboot Nike shoe collection, and Evian’s recycled water bottles.

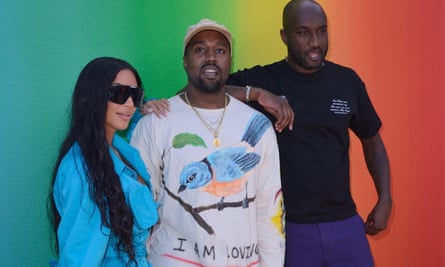

Most significantly, though, was his stunning debut show for Louis Vuitton on an endless open-air rainbow-coloured runway at the Palais Royal in Paris. The 2018 show brought one of the oldest fashion houses into a new era, reinvented as street-inspired, futuristic, Black haute couture. Abloh’s tearful embrace with West as the show ended was recognition of the journey by two Black men who had achieved success beyond their wildest dreams.

So how did a boy born to Ghanian parents and raised in Rockford, Illinois, rise so meteorically? While studying engineering at university, seeing a Caravaggio painting changed his life. He then studied architecture, which laid the foundation for his later work.

“He didn’t study architecture to become an architect; he studied it to learn about the structured process of thinking about how to design” says Quarless. “He knew he was going to apply these to lots of creative ideas swirling in his mind, but which he didn’t necessarily know how to execute yet.”

Abloh quickly realised that to cut through in the fashion world required collaboration and heavyweight names. Cue fellow Chicago icon West.

“Kanye talked about wanting to change rap and had a vision. Virgil also had a vision. He had a hand in Yeezus and My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy,” Quarless says of West’s albums for which Abloh directed the artwork. Yeezus had no cover, just the disc in a see-through CD case – the void representing the “death of the CD”. The next – packaged with a gaudy George Condo painting depicting West, naked and being straddled by a winged woman – was widely censored.

Quarless, who has a background in political film-making, says he was drawn to the project because he sees Abloh as an activist, too, in his own way. “When he went to Louis Vuitton he exploded, not only in how much we were exposed to him, but in helping put young Black creators in positions of power and showing them that anything could be done.

“He supported people, and causes, and was explicit that he was doing this for young Black people – so the world could see what they can do.”

But every cultural icon comes with controversies and criticisms; Abloh’s approach to sharing and copying ideas led to accusations of plagiarism. He screen-printed Ralph Lauren rugby shirts, stuck his Pyrex Vision logo on them – Off-White’s early name – and resold them for exorbitant prices, failing to remove the original tags.

“When you’re a person of colour it’s called stealing,” says Dijon. “When you’re not, it’s called inspiration.”

“The criticism followed him for most of his career,” says Foster. “The level of online fury was unbalanced and unwarranted. Most of the criticism was rooted in racism.”

Quarless defends Abloh on the plagiarism claims: “Black culture, internet culture – these are cultures where things are taken from different places and mashed up, remixed. And he was not against the idea of people copying from him.”

Quarless believes that many more people loved Abloh than hated him – not least because of his philanthropy. Early in the film, McNally, who was active in the George Floyd protests, tells us how Abloh contacted her on Instagram and helped raise $80,000 to build a school for Black feminist politics. Much of the funding came from selling a line of Off-White T-shirts emblazoned with the words “I support Black women”.

Diagnosed with angiosarcoma, a rare form of cancer, in 2019, Abloh did not publicly disclose his illness – which is why his death was such a hammer blow. “When we started reaching out to people, it was still raw,” says Quarless. “Virgil meant so much to so many people. You could definitely make an eight-hour series about him. His life was so rich.”

The film concludes with footage of the Louis Vuitton tribute show, Virgil Was Here. In her eulogy, Foster says: “I really wish I’d got to say thank you in a meaningful way. I didn’t get to do that.”