As unrest broke out in 2006 in countries neighbouring Somalia, and threatened by the prospect of an arranged marriage, Ifrah Ahmed, who was aged 17 at the time, fled to Ethiopia and secured a ticket to fly out of the country. She found herself seeking asylum in Ireland. She couldn’t speak any English and had no clue where she was upon arrival.

“It was very cold and I was freezing and then I was lucky when I was given a jumper by a lady.”

Now warm, Ifrah, seeking asylum in her new home, underwent compulsory medical examinations which included a smear test, to screen for cervical cancer.

“The nurses told me that now I have to lay down, now I have to do a smear test. So I did what they told me. Once they came down and looked at me, they were really shocked. They started shouting and were saying ‘what happened’ several times over. Then they called other people. There were a lot of them. They surrounded me and kept asking me ‘how did this happen? How did you get injured?’”

What the medical staff at the hospital had noticed was that Ifrah’s genitals had been mutilated.

Ifrah Ahmed was eight years old when she went through Female Genital Mutilation, the cultural practice involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

Wood sticks, stones and scissors are used as tools to cut the female genitalia. It is a ritual believed to ‘purify and make a young girl clean’.

FGM is mostly carried out on young girls between infancy and age 15 and has been carried out on more than 200 million girls worldwide especially in Africa, the Middle East and Asia where the practice is concentrated.

It is a violation of the human rights of girls and women.

“When I saw that they didn’t know, I saw that there was something wrong. I realised that this had not been every woman’s experience. So I had to tell them about it.”

This was the first time Ifrah shared her story about her ordeal to anyone. When she was asked why it happened, she couldn’t say because according to cultural practices in her home country, Somalia, nobody explains to a girl why she goes through FGM.

Ifrah says back then, you’ll never know of it, till it’s about to happen in the next few seconds.

After her revealing hospital visit, Ifrah returned to the asylum and spoke to other women she came with on her flight. She found out that other women had also gone through the same experience as her but from other countries.

“I was asking questions about the hospital and I remember there was this young woman from Guinea who talked about her own story and how she was cut; saying she was cut with a stone. They were talking about how when they were having babies, they had to go through caesarean section because they couldn’t have a vaginal birth because they had been sewn up.”

When I saw every woman complaining, I saw that they didn’t know how to communicate their anger and disagreement with the practice so I told myself that I would be their voice.

It was then that Ifrah would begin to advocate for girls and women and start her global fight against FGM over the next six years. She would speak to doctors, in schools, at conferences, with world leaders, social workers and managed to bring in a piece of legislation to the country’s parliament which meant that FGM banned in Ireland in 2012.

“I vowed that I won’t allow any woman to go through this and I said I have to do something about it.”

She also returned to Somalia to speak with and challenge the President on the issue.

“I felt that if I had a voice in Ireland, in the country I didn’t speak the language, a country that I didn’t have any connection with, if I passed a bill there, then I could do the same in Somalia.”

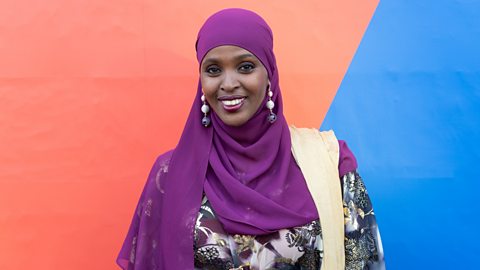

Ifrah Ahmed has since founded the Ifrah Foundation, a charity devoted to stopping FGM around the world. She was one of the first Somali women to speak publicly about FGM.

Her journey from being a powerless victim, subject to a horrific ritual to a powerful role model has been dramatised in a film called ‘A Girl from Mogadishu’.

She just power for power less women we need more than this